Falconry Month at Birds and Booze:

I’ve decided to dedicate this month of March 2019 to wines and beers related to the history of falconry – or hawking – for no other reason than that I’ve recently acquired several bottles adorned with mostly medieval European iconography relating to this “sport of kings”. While the hunting of game with trained birds of prey can be a controversial topic among birders, falconry was a valuable early source of information on birds, and its history, culture, and imagery continue to fascinate bird lovers, as we shall see.

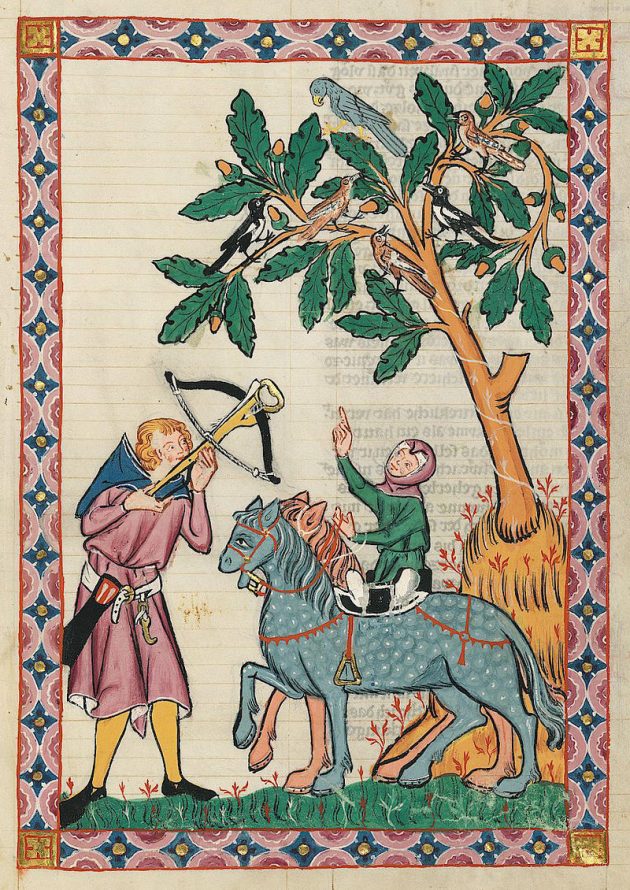

Likening the pursuit of love – with all its delights and misfortunes – to the equally capricious excitement of the hunt is a metaphor that has undoubtedly existed since humankind first learned to kill its food, long ago in our Stone Age past. But perhaps no other age drew this comparison as frequently and strongly as did medieval Europe. Iconography of the Middle Ages abounds with images depicting the hunt as the heroic leisure pastime of a noble warrior class, an idealized sport pursued by lusty knights, alongside equally chivalric endeavors such as the composition of courtly love poetry or falconry.

Unlike other forms of hunting, however, medieval falconry was considered a permissible pastime for women of the time as well, undoubtedly because the killing was done by proxy – courtesy of a trained bird of prey – with no exertion or bloodshed on the part of its human participants. And as it was open to both men and women, the sport also afforded both sexes ample opportunity to spend time out of doors in one another’s company – time that undoubtedly led to courtship in many cases. So, as both a form of hunting and an invitation to courtship (and perhaps to even less respectable amorous acts), falconry in the Middle Ages developed strong associations with love, both courtly and carnal. In The Art of Medieval Hunting: The Hound and the Hawk, historian John Cummins compares the consummation of an amorous pursuit in medieval literature to the brutally visceral moment of contact between a raptor and its quarry, describing the following scene:

“[T]he intense imagery of the triumphant falcon…mantling and panting over its prey: lovemaking as killing and love as a chase, a flight of heart-stretching endeavor which ends with the two participants enmeshed on the earth; a soaring and a stooping.

And, if that weren’t enough, author and medievalist Danièle Cybulskie points out that – besides the obvious element of the chase – falconry relies on blindfolding, luring, and bondage via leather straps (jesses), among other suggestive motifs. This may all be reading too much into it, but falconry probably has birding beat when it comes to latent eroticism: usually the sexiest thing one can say about birding is that it’s a glorified form of voyeurism!

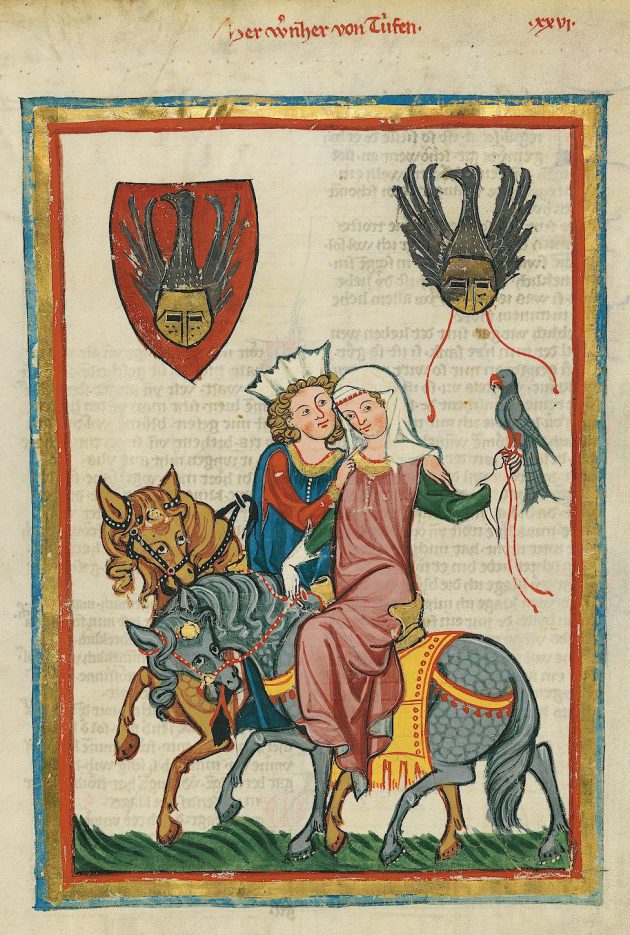

One of the most celebrated sources of romantic medieval falconry imagery is the Codex Manesse. Unlike De arte venandi cum avibus of Frederick II we saw last week, the Codex Manesse is neither a treatise on falconry nor early collection of avian observations, but an extensive collection of the medieval German courtly love poetry known as Minnesang, a tradition of lyric amorous poetry falling somewhere between the more famous art of the troubadours and the later Meistersinger of Wagnerian opera fame.

Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor and father of Frederick II, as portrayed in the Codex Manesse. Henry is included in the poetry collection not as a royal patron of the arts, but a practitioner himself: three of the poems of the Codex are attributed to the emperor. Henry VI seems not to have shared his son’s obsessive interest in birds and falconry, however.

The Codex Manesse was created in early 14th-century Zürich and contains over 6,000 strophes of Middle High German lyric poetry. It is also lavishly adorned with 137 full-page miniature illustrations in the High Gothic style, many of which depict birds of prey in hunting scenes and in more intimate episodes of chivalric love. Compared to De arte venandi cum avibus, the Codex Manesse is more medieval bodice-ripper than proto-field guide.

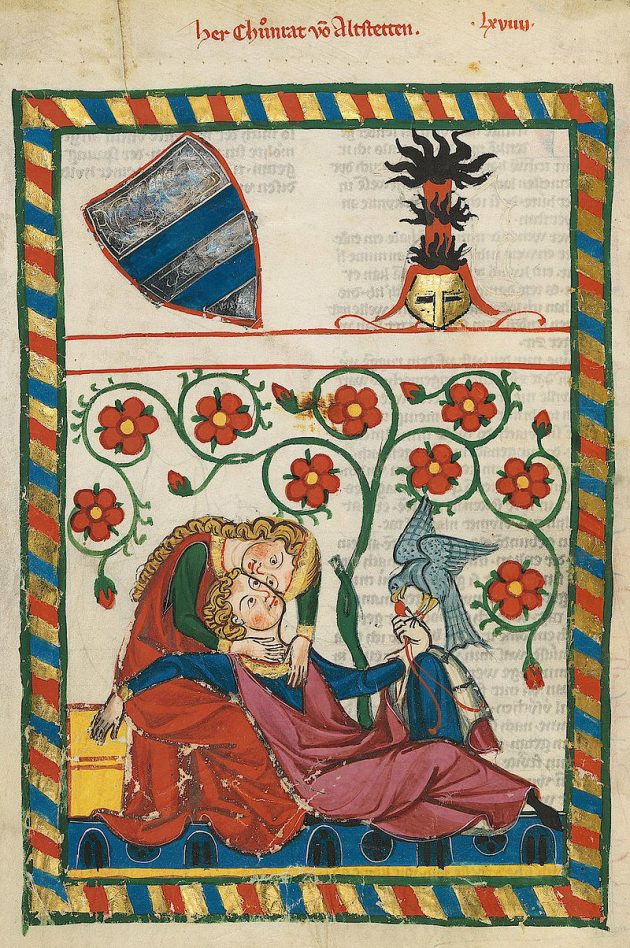

Perhaps the most famous miniature from the Codex Manesse depicts a reclining couple with a bird of prey perched on the gloved hand of the knight as he rests in the embrace of his lady. According to the caption, the man is Lord Konrad of Altstetten, a Minnesang poet of the upper Rhine Valley in the 1320s. Less identifiable is the bird, but this ambiguity takes nothing away from the charm of the wonderful composition of the image, which adorns the bottle of our wine this week: a 2016 Aglianico from Campania by Terredora DiPaolo.

This southern Italian red is made from the same ancient Aglianico grape as last week’s wine from Basilicata, but the vineyards of Terredora Dipaolo are found west of the Vulture region, in neighboring Campania. Though it’s a full year younger than the Basilicata Aglianico wine, this Campanian example seems softer already, with less pronounced tannins and acidity, and perhaps more ready to drink at this younger stage. The bouquet is plummy and full of dark fruit, with touches of leather, cedar, and vanilla. There is a lusty aroma of cacao, which adds depth to the slightly tart, black cherry palate.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Terredora Dipaolo: Aglianico Campania (2016)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Cool stuff, Tristan, as always. But you can’t really talk about falconry and the Manesse ms. without at least mentioning the Kürnberger’s falcon song: https://www.bartleby.com/177/9.html .

Thanks, Rick. The only Manesse texts I’ve really seen before are from musical settings on recordings of medieval music (mostly of Neidhart and Walther von der Vogelweide). But this is fantastic; I’ll have to work it into my review as an addendum. Cheers!