Gulls make my head spin. You know why. To borrow from the Patty Duke Show theme song (I’m dating myself, I don’t care): “They laugh alike, they walk alike, at times they even talk alike, you can lose your mind …” I had hoped that examining this latest identification guide, Gulls of the World: A Photographic Field Guide by Klaus Malling Olsen, would help the dizziness, and it has, but in some ways it has made it worse. So many birds of white and gray touched with black. So many immature birds utilizing a palette of brown and ecru, burnt umber, white and black. So many species that change eye color or leg color as they age. Not to mention the hybrids. The many images of gulls presented by this field guide with their detailed captions are the best reasons to purchase and use this book. They also present a challenge to those of us who, well, are not in love with gulls.

Gulls of the World: A Photographic Field Guide is a successor, or companion, as the author terms it, to Klaus Malling Olsen’s classic guide, Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America (Helm, 2004*). This encyclopedic identification guide covered 43 species in 608 pages, and was illustrated with both Hans Larsson’s exceptional artwork and color photographs by multiple photographers. Gulls of the World is meant to cover more geographic area (add South America, Australia and the Arctic and any other parts of the world not covered in the first book) and less detail. And, it’s all photographs—6 to 38 for each species, depending, of course, on identification difficulty. It covers 61 species (or, more accurately, gulls that the author thinks are worthy of their own individual treatments) in 368 pages (PUP lists it as 488 pages, it’s not). Malling Olsen succinctly states, “The aim of the book is to present identification in a more concise way, supported by numerous photos, the majority of which have never been published for a large readership before.”

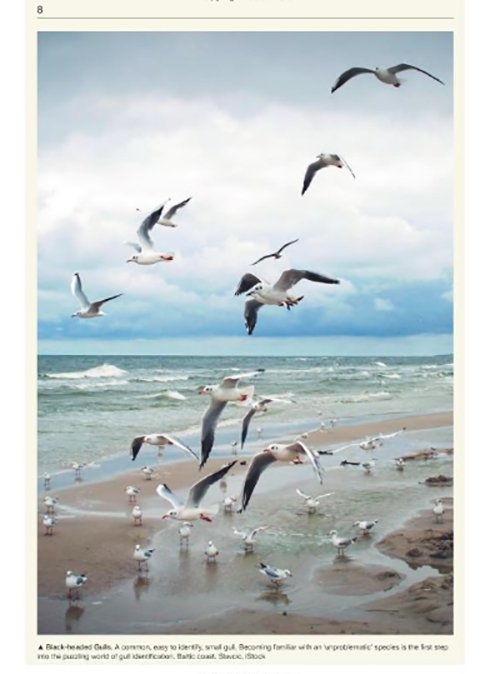

Black Headed Gulls, Baltic Coast, Introduction

Introduction

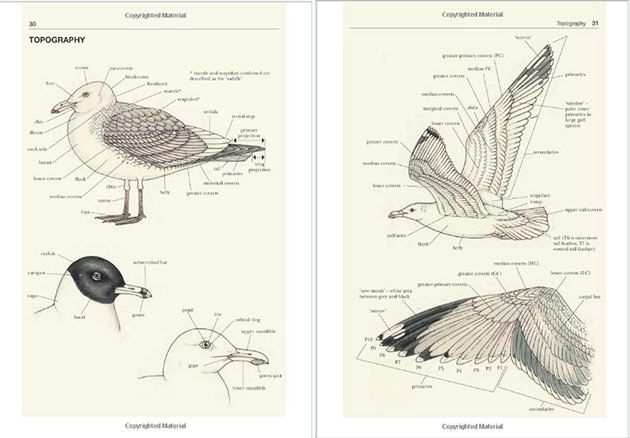

The 26-page Introduction is a mini-tutorial in gull identification, covering aging, molt, and factors that affect molt (geographic area, wear, disease, color abnormalities, oil staining), perception of plumage (sunlight chiefly), ‘judging size and jizz,’ and hybridization. It’s also a terse introduction to the specialized vocabulary needed for gull identification. If you’re not familiar with terms like orbital ring, saddle, gonys, or how the primary feathers are numbered, then I highly recommend you bookmark the Topography diagrams of gull parts. And, if you’ve never used the Kodak grey scale Color Separation Guide, then you must read ‘Introduction to The Species Accounts.’ This section also offers additional phrase definitions (‘string of pearls’ brings back happy memories of my first Slaty-backed Gull; I’ve never used ‘venetian blind’ effect). Describing gull plumage is a combination of science, graphic art, and visual metaphor.

Taxonomy and gulls can be a complicated situation; classification systems and ornithologists are fuzzy about a number of gull species and subspecies. Malling Olsen has made his own decisions, based on research (some not available when he was writing his previous book), on which gulls to treat fully, even though they are considered subspecies in current classifications (Steppe, Mongolian, Azores, Baltic, and Kamchatka Gulls). He explains this reasoning briefly in the Introduction. Vega Gull, considered a subspecies in the AOS classification system, is also given its own chapter. And, Thayer’s Gull lives! I wish Malling Olsen had written just a little bit more about his taxonomic decisions, as well as some background on the Common Gull complex, which is here divided into three gulls with their own chapters (Common Gull (Larus canus), Kamchatka Gull (Larus (canus) kamtschatschensis), and Mew Gull (Larus brachyrhynchus), with a fourth subspecies, Larus canus heinei, treated as a subspecies of Common Gull. Malling Olsen makes it clear from the beginning, that “the intention is not to present an authorised taxonomic update…” (p.9). However, I think some background on the Common Gull and Herring Gull complexes would be helpful to gull beginners and give the a little structure for field observation.

Topography

Book Organization

The ordering of the Species Accounts is based on Handbook of the Birds of the World, with some rearrangements (p.10). So, we start with Dolphin Gull and end with Red-Legged Kittiwake, a totally different sequence from the 2017 eBird listings. The Table of Contents is the best starting point for finding the gull you want, and with 61 species accounts, listed with common and scientific name, it’s pretty easy to scan and pinpoint a name.

The Index lists gulls by common and scientific name and includes subspecies, but only indexes the text accounts, not the photographs. So, I can go right to the description of Larus canus heinei on page 78, but I need to scan the photo captions to find the gull depicted on pages 83 and 84. The alphabetical ordering of the common and scientific names is unusual, with common names listed beginning with first word (e.g., Heermann’s Gull is under H) and scientific names listed beginning with last word (heermanni, Larus). I suppose this works with such a small family, but it made my librarian brain ache just a little bit.

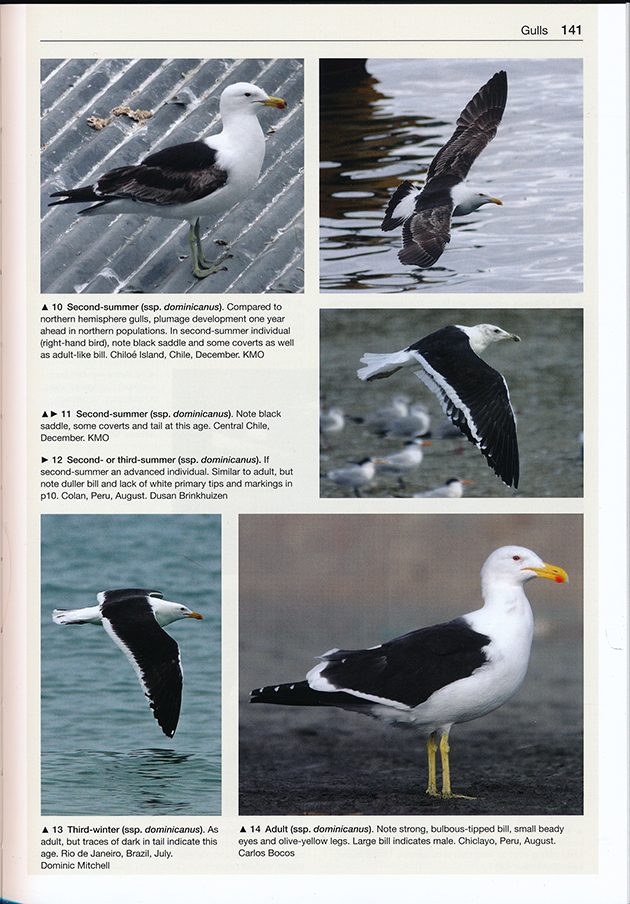

Kelp Gull

Browsing through this book is tough. The pages are labeled on the left with the genus name (for example, Larus) and on the right with the brief title: Gulls. The photos captions begin with the age of the gull and subspecies (if necessary) in bold print, not the name of the gull. This means that when you are browsing through the photographic pages, you often have no idea what gull species you are looking at. At least, I don’t. If I stop and examine the photos, I may figure it out, if it is a species with which I’m familiar, but often even this id is in error because, with few exceptions, gulls around the world look a lot alike! I mean, I thought I was looking at a Greater Black-backed Gull and flipping the pages found out that it was a Kelp Gull. Greater Black-backeds are larger and stockier and adults have ‘slightly paler upperpart,’ but that is difficult to discern in a photograph. The geographic distribution is different, so if I had some basic knowledge I may have been able to figure out the species from the locations of the photos, but first of all, I don’t have this expertise, and second, that’s a lot of work for a search that should take less than a minute. So please, Mr. Malling Olsen, next edition, please add species to the page labels.

Species Accounts

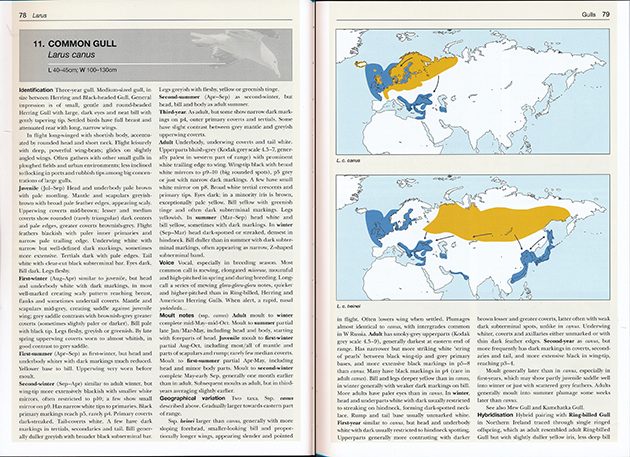

Each Species Account includes: Common and scientific name; measurements, if known; a two-paragraph summary of identification points, including number of years it takes the species to develop into adulthood, shape, ‘jizz,’ and flight style; description of plumages by year and season (juvenile, first-winter, first summer, etc.); brief description of common vocalizations; ‘Moult notes,’ which vary in length depending on usefulness for identification; Geographical variation; Hybridization (most frequent hybrids); Status, habitat and distribution; Similar species; References. Distribution maps, ranging in size from one-eight to one-half of a page, indicate breeding and non-breeding habitats and trace migration routes.

Common Gull Species Account

The sections on plumage are the lengthiest, far more detailed and extensive than any general field guide account, particularly for the four-year gulls, though Olsen refers the reader to his 2004 book for more highly detailed descriptions. A quick comparison of several accounts from both books indicate that the descriptions are re-written, sometimes totally. The difference is that the 2004 volume gives descriptions for identification, and then even more detailed, encyclopedic descriptions of plumage and molt, including measurements. And, of course, the 2004 volume does not include all the gulls of the world.

I was interested to see that Malling Olsen utilizes the ‘years’ approach to describing plumage (first winter, first summer, etc.) rather than the Humphrey-Parkes cycles approach advocated by Steven N. G. Howell & Jon Dunn in Gulls of the Americas. Malling Olsen comments in the Introduction that he finds the latter “less useful for a concise description of how a bird looks at any given time of the year” (p. 28). I don’t feel qualified to judge whether this is good or bad or in-between, but it does make it difficult to use both books at one time. I’ll be interested to read the opinions of gull experts on this question.

I find the References section puzzling, incomplete, and inaccurate. Some Species Accounts have very abbreviated listings (two citations for Hartlaub’s Gull), some have more (18 citations for Common Gull). Articles have been added since the 2004 volume for some, but not all species (let’s face it, not all gull species are of interest to researchers). But, whether the References sections are short or long, whether the citations are old or new really doesn’t matter since they are unusable. The citations consist of author’s last name and year of publication. Period. There is no bibliography at the end of the book giving the full citation, which would easily allow the reader to locate the full text of the article or monograph being referenced. The Introduction tells us to refer to the 2004 volume for the full citations, but this is highly problematic: the book is difficult and expensive to purchase in the U.S. and not held in many libraries, and the 2004 volume does not contain the later citations. (I can’t help wondering if the difference in page length between the publisher’s catalog and the book itself is partially due to the elimination of a back-of-the-book bibliography.) In addition, a fact check of the 18 citations for Common Gull revealed misspellings of three author names, two of which were spelled correctly in the 2004 volume. Not only is this sloppy, it makes looking up the articles even harder.

Vega Gull

Photographs

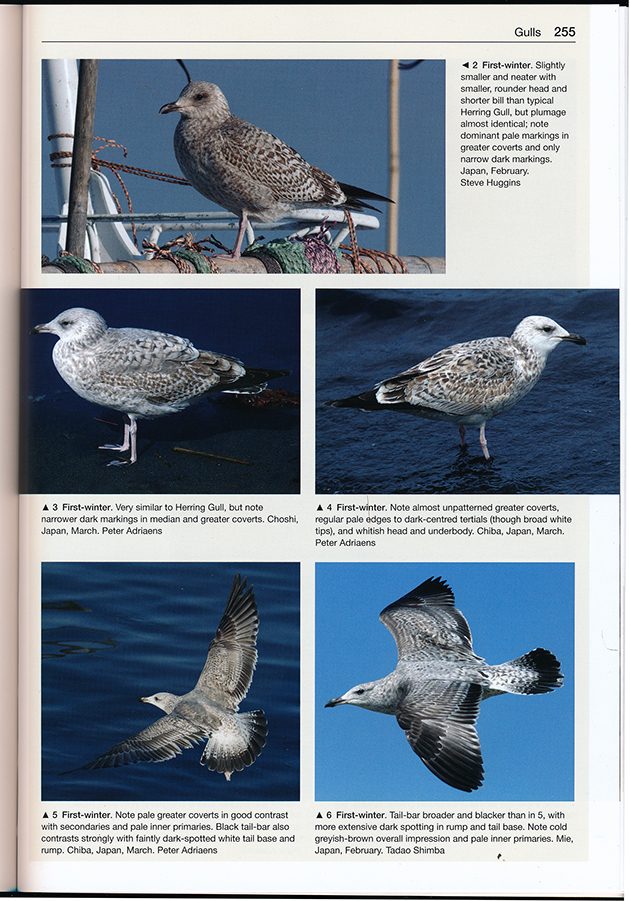

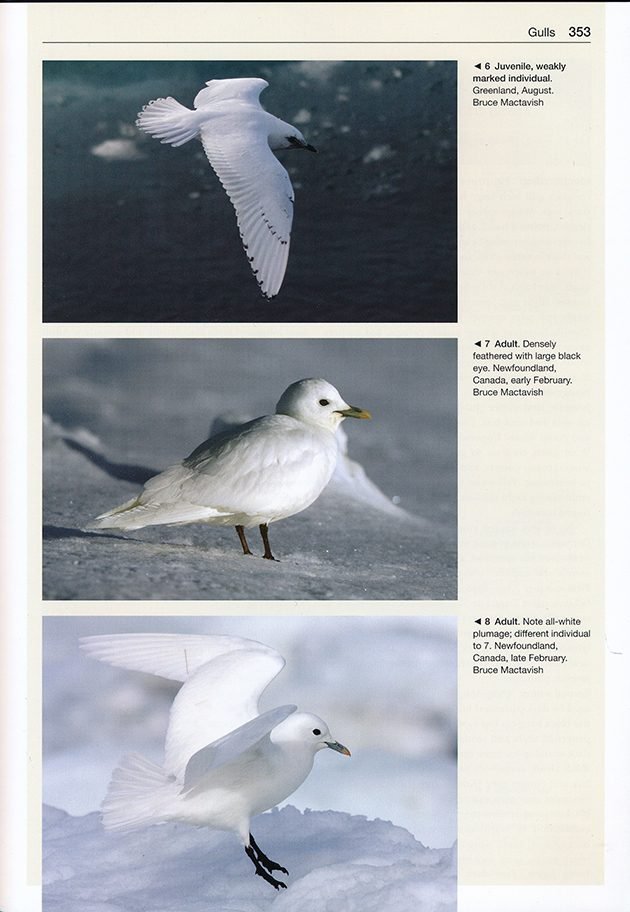

Of course, photographs are the most important part of a photographic guide. The photographs here—images of white, gray, brown birds with yellow or pink legs, black or red or yellow bills, representing each species and subspecies in each plumage stage—illustrate and extend the text sections of the species accounts. They will be invaluable to birders seeking to use their own photographs to identify gull sightings. The publisher catalog says more than 600 photographs. I sat down and counted and got over 900!

Photos are of a fairly large size, at the most there are five to a page. Effort has clearly been made to arrange them logically within the species account–birds of the same age and subspecies grouped together, and on the page–facing the same direction most of the time and, when not, placed in a pleasing counterpoint; balancing size, situating captions so you know which caption belongs to which photo (the little arrows help, but it’s pretty apparent from the placement).

Quality ranges from bright and sharp to less-than-bright and sharp (mostly when the gull blends with a background of other gulls or a dark sky), but I have not found a bad one in the book, and every photo illustrates a point. There are also some beautiful images here–the two-page spread of Black-legged Kittiwakes that precedes the Species Accounts is heart-stopping–but, we’re looking at jizz, wing-tips, bill color, molt, patterning, mirrors and strings of pearls here, not the wonderment of hundreds of small gulls flying against a snowy winter sky.

Captions note plumage features being illustrated and often compare these features with those of a similar species or subspecies. Each photograph is also labeled with photographer’s name, month in which the photo was taken, and location. It also points out and describes distinguishing field marks, plumage features, and individual variation. I have to note here that I do not have the expertise to determine if the captions are accurate. This is the area where photographic guides sometimes (not always!) fall down, so I will be scanning the Internet for reviews by some of our tribe’s gull experts and enthusiasts.

As usual, I was curious about the process of how this book was made, and how Olsen obtained over 900 gull photographs. He notes in the Acknowledgements that photographs were obtained by the publishers initially, and then by requests to gull-oriented Facebook groups. This downplays the fact that many of the photographs are by Olsen himself, something I realized only after browsing through the book and noticing many images attributed to KMO and finally figuring out that this was the author’s initials and not a photographic collective. Another photographer name many readers may recognize is Amar Ayyash, the author of the blog Anything Larus and co-admin of the Gulls of North America Facebook group.

Author

Klaus Malling Olsen is a Danish field ornithologist, author, tour leader, and speaker who specializes in difficult birds of the sea. In addition to the two gull books cited here, he has authored Skuas and Jaegers: A Guide to the Skuas and Jaegers of the World (Yale Univ. Press, 1997) and Terns of Europe and North America (with Hans Larsson, Helm, 1995), both acknowledged to be the authoritative works on their respective families. He’s also written papers on field identification and distribution, is active in the Danish birding community, including stints on the Danish Rarities Committee, and has an active Facebook page with a surprising number of photos of raptors.

Conclusion

If you love gulls, if you think you may love gulls in the future, if you are interested in gull identification for any reason, buy this book now. It is comprehensive, authoritative, current, visually outstanding, and, if it is anything like its few predecessors, will have a very short shelf life. I don’t know why, but books on gulls go out of print very quickly. Maybe it’s because there are many more gull enthusiasts than we know, birders and others who worship gulls in secret? This is not a perfect book, but I think its high-level of information by the world expert in the field overall trumps problems with organization and references. (And, hopefully, the publisher will make a full list of references available online, similar to what CSIRO did with the index for The Australian Bird Guide.)

But, what if you already own Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America and/or Gulls of the Americas? What is you don’t intend to bird the world and see all species of gulls? Gulls of the World offers a more focused approach to identification, making it easier to use for that purpose, incorporates recent research, and has all those great photographs illustrating identification features for all plumages and subspecies. These are also easier to use, with captions next to the photos rather than down at the bottom. If you don’t plan to leave North American shores, then Gulls of the Americas will probably suffice as an identification resource. It’s an excellent book, with specific information on North American distribution and a more taxonomically structured approach to grouping species accounts. It is also out-of-print.

Ivory Gull

And, if you don’t intend to ever bird outside of North America and will have no need of an identification guide to gulls of the world, then I urge you to rethink your birding goals. Because, despite their confusing plumage and sometimes annoying behavior, gulls can also be fun birds to observe. And, beautiful. And, challenging. Think of a pure white adult Ivory Gull flying into harbor; the striking beauty of all the hooded gulls; the vulnerable status of the Lava Gull, down to a population of 300 pairs, maybe less; the raucous cries of a mixed flock of gulls following a fishing boat. Wherever you travel, there will be gulls. It’s good to have tools to help us know their names.

* Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America by Klaus Malling Olsen and Hans Larsson was published by Christopher Helm, an imprint of Bloomsbury Books, in 2003. A corrected version was published in 2004 and owners of the previous edition were allowed to exchange books.

Gulls of the World: A Photographic Guide

by Klaus Malling Olsen

Princeton University Press, 2018

488 pages, 7 x 1.2 x 9.8 inches

ISBN-10: 0691180598; ISBN-13: 978-0691180595

$45.00 (substantial discounts available from the usual suspects)

Thank you for reminding me of the awesome that is Amar Ayyash! #imisschicago

Amar’s review of this title will be in the next issue of Birding.

Meanwhile, Donna, bless you a thousand times for pointing out the inadequate running headers — a major annoyance! Great reiew all around.

Thank you Meredith and Rick. Very much looking forward to Amar’s review. This was one of the most challenging identification guides I’ve assigned myself to review.

Thanks for this review. Great work, congratulations!