Ecology is amazing. We see interrelationships between plants, animals, and other features of a biological system that can be very complex and in various ways make sense. But we also know from basic evolutionary theory that evolution works mainly at the level of the individuals (more or less). So these complex ecological interactions and systems must emerge as a result of individual behaviors, which also means to some extent, at levels within (below) the species we see interacting.

New research on bluebirds helps address this question. In the American west, fires open up habitats for passerine birds. One of the species that soon becomes abundant in fire disturbed habitats is the bluebird. But usually, it is the Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) and not the Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides)that does better and takes over this new habitat first. What is the mechanism for this?

It turns out, it is hormones.

From the abstract of the study:

An important question in ecology is how mechanistic processes occurring among individuals drive large-scale patterns of community formation and change. Here we show that in two species of bluebirds, cycles of replacement of one by the other emerge as an indirect consequence of maternal influence on offspring behavior in response to local resource availability. … we found that western bluebirds, the more competitive species, bias the birth order of offspring by sex in a way that influences offspring aggression and dispersal, setting the stage for rapid increases in population density that ultimately result in the replacement of their sister species. Our results provide insight into how predictable community dynamics can occur despite the contingency of local behavioral interactions

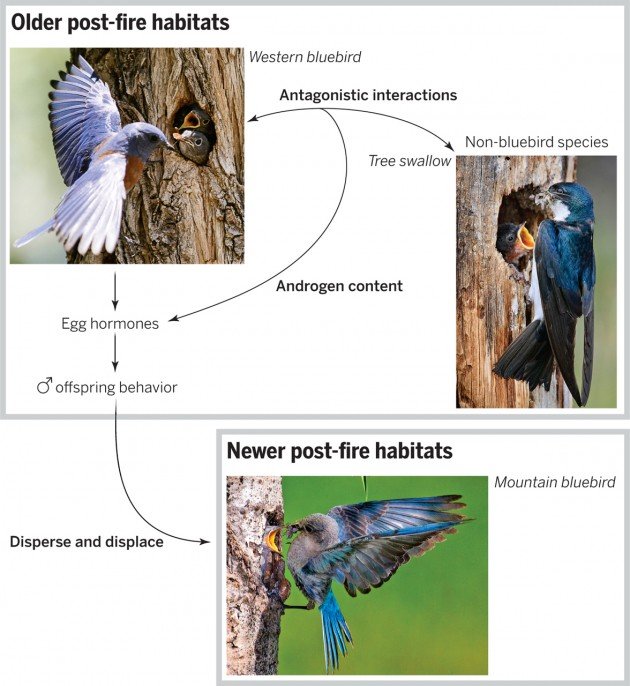

Here it is in graphic form:

Original Caption from Science Magazine: Duckworth et al. (4) show that female western bluebirds experiencing increased conflict with individuals from non-bluebird species have more androgens in their eggs and produce sons that hatch early. These males are more aggressive and disperse to newer post-fire habitats, where they displace mountain bluebirds. Non-bluebird species thus indirectly affect (13) the distribution of mountain bluebirds. This hormone-mediated maternal effect on the behavior of individual male offspring in turn affects higher ecological scales by influencing the distribution and abundance of bluebird species in these communities.

The researchers demonstrate that maternal effects can determine the competitive attributes of the birds. The eggs of Western Bluebirds eggs hatch asynchronously, and males that hatch earlier are more aggressive in their dispersal and more likely to move into the new fire disturbed habitats. They then outcompete the local Mountain Bluebirds. They acquire large territories in so doing. The scientists artificially increased the number of available nest cavities for some but not all females and found that females who had access to extra nest cavities produced fewer of these early hatching, aggressive males. This indicates that nest cavity availability, which could be monitored by the adult reproducing birds, induces the maternal effect (as opposed to other factors such as population density or food availability).

The mechanism that allows for this seems to be changes in the production of androgens in the females producing the competitive males.

The paper: Duckworth, Renee; Virgina Belloni, Samantha Anderson. 2015. Cycles of species replacement emerge from locally induced maternal effects on offspring behavior in a passerine bird. Science 347(6224):875-877.

Photo of Western Bluebird from HERE.

Leave a Comment