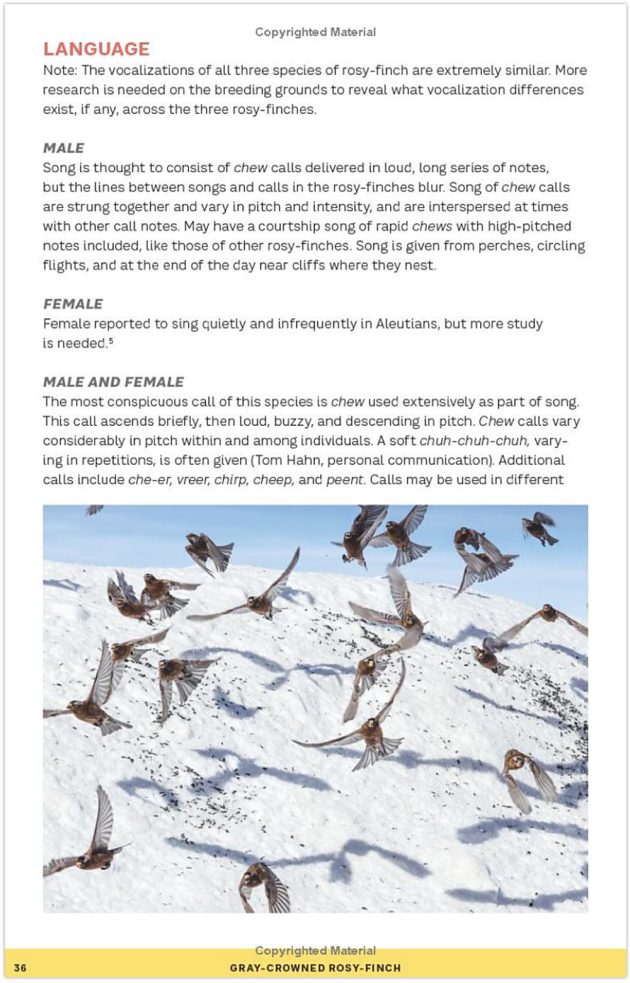

It’s a freezing, quiet January morning in Denver, Colorado. The year is 2011 and I might be the only person left in the hotel. Everyone else at the academic conference left early the day before–panels cancelled, vendors packed–in fear of a major snowstorm. Not me. This was good news to me and instead of leaving early, I extended my stay by one day. Now I was headed west in my rental car, praying, hoping. The roads were already plowed, because in Denver they know how to handle snow, but surprisingly only one other person was at Red Rocks Park when I arrived, a local birder who knew his stuff. “They’re not here yet, but they’ll be coming down,” he told me, “Too much snow in the mountains, they’ll want to eat.” And they did come down. Small, rotund balls of energy with conical bills, dressed in subtle shades of brown and black, silvery white and rosy pink, the latter barely showing in the darkness of the cloudy morning. They fly too quickly to the feeders and then back to the skies, chittering in a cacophony of indistinguishable ‘chews’ and ‘vreers,’ but my new companion helps sort them out: Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch, the only rosy-finch I had already seen when I visited four days ago; Brown-capped Rosy-Finch, arguably the plainest of the three; and one or two Black Rosy-finches, the easiest to distinguish with its silver-gray cap contrasting with deep dark plumage. There are also at least six “Hepburn’s Rosy-Finches,” a subspecies of Gray-crowned, which really excites my companion. It’s very cold, 2-degrees Fahrenheit according to historical records, and there are still snow flurries, but I have no memory of cold or wet, only the magic of watching these birds flying in, the remnants of their breakfast falling to crowds of Dark-eyed Juncos (Slate-colored, Oregon, Pink-sided, Gray-headed), White-crowned Sparrows, and one, rare for the area, Harris’s Sparrow. It was a magic morning.

I think every birder has a finch story, whether it’s seeing Rosy-finches in the snow in Colorado or hearing Evening Grosbeaks migrate at night over New York City or patiently explaining to a friend that the bright yellow bird with black head, black wings, and bright yellow bill at her feeder in June really is the same species as the dingy bird she saw in February (really! look in the field guide!). Lillian Stokes and Matthew A. Young certainly have their finch-spark story; it involves Red Crossbills and their vocalizations, and it’s how they met, the beginning of their collaboration on this unique guide. So, a happy welcome to The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada, the newest addition to the wonderful world of bird family guides! It’s the identification guide (and more) that many of us needed though we may not have realized it till it was sitting in front of us, bright yellow (like the American Goldfinch that so puzzled my friend and which is the featured bird on the cover), bursting with facts, photos, science, and a love for finches.

It’s a fascinating group, including some of our most familiar feeder birds (American Goldfinch, House Finch), some of our prettiest species (think of the raspberry tones of the Purple Finch), and some of our most captivating, elusive species (Red Crossbill, White-winged Crossbill, all three Rosy-Finches, Evening Grosbeak, Common Redpoll and Hoary Redpoll–now Redpoll, but still two species when this guide was written). Stokes and Young have combined their specific strengths to produce a comprehensive, well-researched treatment enlivened by over 345 photographs; expressive, sometimes whimsical, introductory essays; and the continuous thought that observing finches is good for our health and the world. Like all the books in the Stokes Guide series, it is exquisitely organized and designed, with a lot of thought for how people will be using it. It also gives a lot of attention to backyard bird feeding, a topic usually ignored by field guide editors but not surprising in a Stokes branded guide. The series has long specialized in books that educate beginning birders and backyard feeder enthusiasts (which is not to say that it doesn’t also include guides useful for more expert birders! It does! This guide is an example!)

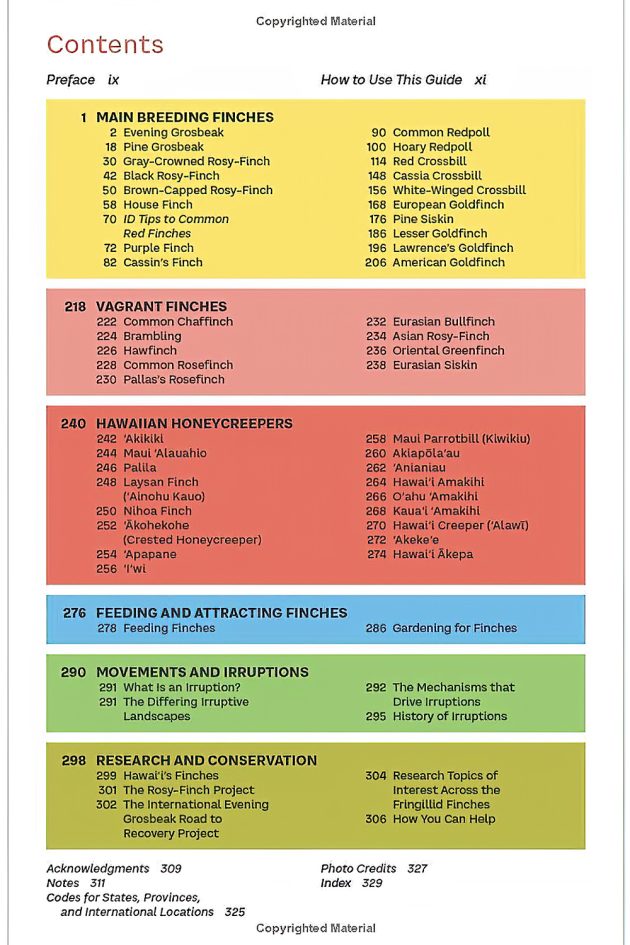

There are over 235 species in the family Fringillidae according to Cornell University’s Birds of the World. It’s a family distributed across the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa (but not Australia, their finches belong to a different family) with a complicated phylogenic history that has been turned topsy turvy by molecular DNA studies. The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada covers 44 species: 18 species that breed in North America, nine vagrant species, and 17 Hawaiian Honeycreepers (it turns honeycreepers are finches–who knew? probably everyone but me). The bulk of the guide is devoted to the “Main Breeding Finches,” 217 pages. These are in-depth Species Accounts, including identification information; subspecies listing; distribution maps; detailed descriptions of vocalizations including spectograms; irruptive movements; summaries of feeding, nesting and breeding behaviors, including backyard and garden feeding; conservation status; introductory “Quick Take” essays and “Deeper Dive” research nuggets. Length of each species account varies, depending on the complexity of each bird’s life history. Lesser Goldfinch gets 10 pages, Red Crossbill gets 34 pages. This section includes European Goldfinch, not a species I think of as North American, but the American Birding Association Checklist Committee does acknowledge that there are breeding populations in specific geographic areas. Overall, what you have here is much more than what you’ll find in a field guide, it’s more like a handbook or a Birds of the World chapter, but more readable.

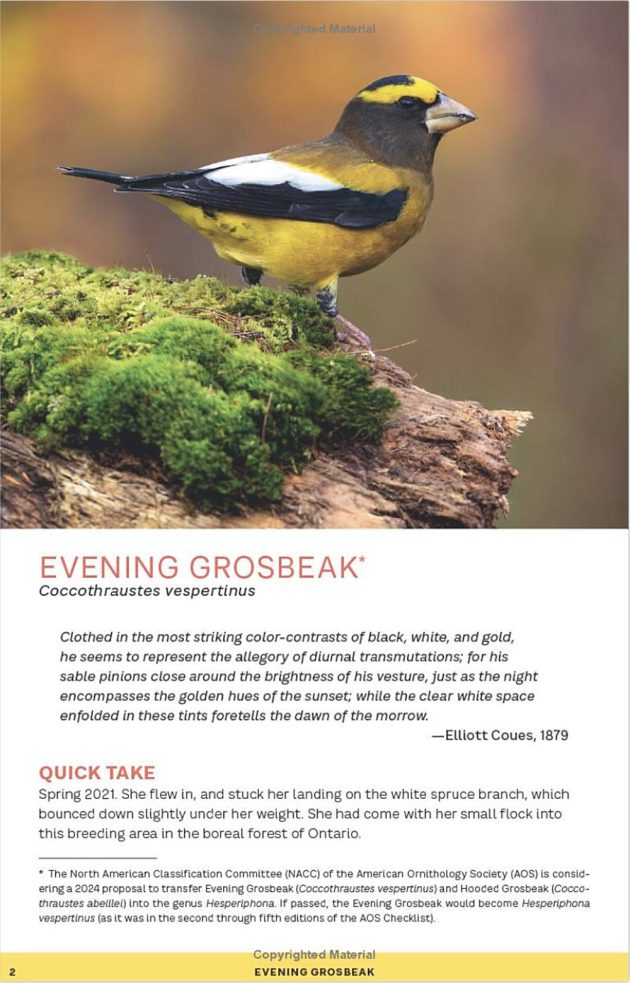

Evening Grosbeak, page 2 © 2024 by Lillian Q. Stokes & Matthew A. Young

The section on Vagrant Finches starts with a “Quick Take” essay about vagrancy. One of the best things about this guide is the care the authors take to make concepts like vagrancy (and irruptive movements) clear to beginning birders and non-birders. The species accounts are brief, two pages long, one page for text and one page for photographs. Identification information focuses on how the vagrants are likely to appear when they show up in North America. The “Status and Distribution” section includes the American Birding Association checklist code and significant sightings. Some of these species are regularly occurring vagrants, like Brambling, some are very rare birds that we have very little chance of seeing in North America, like Pallas’s Rosefinch, Code 5. (The authors take special note of the photograph of the one vagrant that showed up on St. Paul Island, Alaska in 2015; it’s by Tom Johnson and they sweetly mourn his death). Most of the images of the vagrant birds show them in their native country.

The Hawaiian Honeycreeper species accounts are also limited to two pages; there are distribution maps for some species and a “Fun Fact” for each species–about their behavior or physiology or role in Hawaiian folklore. The introductory “Quick Take” succinctly summaries the conservation challenges faced by these birds as well as their evolutionary development and the Conservation sections in the species accounts expands on this a bit, giving their IUCN status and quotes from scientists working on their conservation (but not for the ‘Akikiki, which is considered “functionally extinct”). This is supplemented by the back-of-the-book section “Research and Conservation,” which cites the work of the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project and the American Bird Conservancy in captive conservation and release and battling the evil mosquitos that transmit avian pox. This is no substitute for a book devoted to the birds of Hawaii, but their inclusion here does two things–re-orients our thinking in terms of evolution and taxonomic relationships (so, Hawaiian honeycreepers are finches–still wrapping my head around that) and focuses our attention on the need to support these conservation projects.

There are three additional sections that give greater context to the species accounts: Feeding and Attracting Finches, Movements and Irruptions, and Research and Conservation. The feeding section complements the species focused “At Your Feeder” sections in the species accounts, listing types of seed finches will eat, the variety of feeders they will use, and, sadly, diseases finches are vulnerable too and what to do to try to prevent them, particularly Mycoplasmal conjunctivitis. I wish I could use some of the information in the gardening section, which encourages using native plants and overgrown lawns to feed finches.

Research and Conservation can only highlight some of the conservation projects, past and present, that are attempting the stem the startling loss of finch species, primarily the Hawaiian finches (currently 16 species in the wild, down from over 50) and Evening Grosbeak (92% decline since 1970). Movements and Irruptions is a chapter I need to read again. This is a topic that seems simple till it isn’t. The historical account here of notable irruptions by different finch species and the pictorial graphic of which seeds drive irruptions of which finch species are very helpful, though it also makes me sad that I missed the superflight of 2020-2021 (damn you, Covid).

The listings of “Research Topics of Interest Across the Fringillid Finches” and “How You Can Help” echoes some of the discussions of the Facebook group “Finches, Irruptions, and Mast Crops” administered (and I think started) by Matt Young. It’s an active group, probably especially active this week with the release of the Annual Winter Finch Forecast, an analysis of mast crops and boreal finch movements followed religiously by finch enthusiasts and birders who yearn to see Evening Grosbeaks at their feeders and Red Polls at the beach. (The Finch Forecast was developed by Ron Pittaway and is now being continued by Tyler Hoar with the assistance and support of many observers and birders, including Matthew Young.)

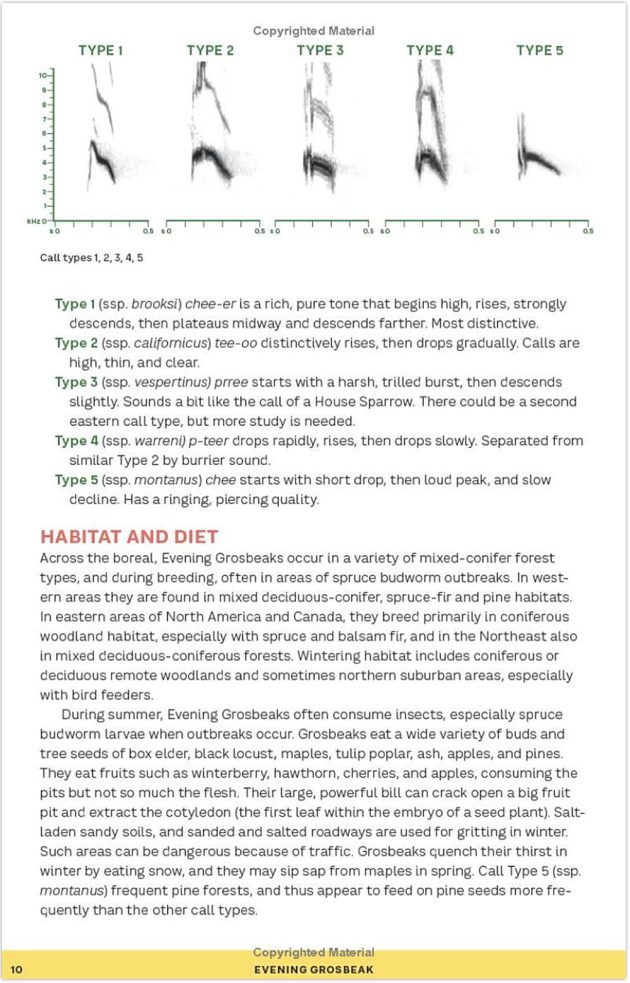

Evening Grosbeak, page 10 © 2024 by Lillian Q. Stokes & Matthew A. Young

The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada is lushly illustrated with photographs, distribution maps, spectograms, and tables of information. The Red Crossbill chapter is full of tables showing food source preference by bird type and by month, I love them. Spectograms are essential when writing about finches, particularly Red Crossbills. The authors treat each of the 12 flight calls in detail, a full page for each (including Cassia Crossbill, which also has its own separate account, but it makes sense to include it here), showing the interplay between geographical location, food source, irruptive movements, and sound. If you are at all interested in crossbills, this section alone makes acquiring this book worthwhile.

Photographs are informational, illustrating species at different ages and genders, in their habitats, and a few showing behavior. There are also decorative photographs, illustrating the beauty of the birds, such as Marie Read’s dreamy image of Common Redpolls in the snow and Alan Murphy’s full page twin images of crossbills in on top of their pine trees. Portrait photographs–close-ups illustrating age, gender or subspecies–are labelled on the photo itself for age, gender, scientific name if illustrating a subspecies, place and year. Photographer credits are given in the back of the book; many of the images are by Lillian Stokes, a couple are by Matt Young, and others are by birders and professional bird photographers whose names are familiar: Brian E. Small, Marie Read, Alan Murphy, Jack Jeffrey, Melissa Groo, Dorian Anderson, Nathan Goldberg, Yve Morrell, Tamara McQuade, Jay McGown amongst others.

While Stokes and Young were writing this book, two issues that affected finches–one taxonomic, one related to taxonomy–were gathering a lot of attention in the North American birding world. There was a proposal on the plate of the American Ornithological Society’s North American Classification Committee to “lump” Common Redpoll and Hoary Redpoll, an action long advocated by some birders that seemed to be a slam dunk after a 2021 genetic study showed few differences between the two “species.” And there was the highly controversial resolution by the AOS to rename the common names of birds named for people, which will affect three finch names. The redpolls were indeed lumped (along with a third, European species, Lesser Redpoll) into Redpoll, Acanthis flammea, after the book went to press. Stokes and Young were prepared. They note at the beginning of both Common Redpoll and Hoary Redpoll chapters that the birds are part of the “Redpoll complex” “to reflect the potential changing taxonomic status,” and explain in the Hoary Redpoll account what will happen if the reclassification is approved, one Redpoll species with six subspecies (they were slightly incorrect on one item, the new, lumped species is Redpoll, not Common Redpoll). So, the information is there, purists just need to annotate their chapter headings. There are similar notes for Cassin’s Finch, Lawrence’s Goldfinch, and Pallas’s Rosefinch, with no opinions attached.

The amount of research that went into this guide is impressive. The authors clearly read every scientific paper and followed every ornithological research project and argument till the day the manuscript went to press. Scientific authorities for the text of each chapter are meticulously listed in the Notes section in the back of the book, 10-and-a-half pages long. This is not surprising. Though they come from different backgrounds, both authors are known in the birding world for their expertise and enthusiasm for learning. Lillian Stokes has co-written over 35 bird guides with her husband Don, including the Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America (2010), The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds: Eastern Region & Western Region (2013), Stokes Beginner’s Guide to Bird Feeding (2002), Stokes Beginner’s Guide to Hummingbirds (2002), Stokes Beginner’s Guide to Shorebirds (2001), and the Stokes Field Guide to Bird Songs. (Sadly, as Lillian explains in the preface, Don has been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia and is a long-term care facility.)

Matthew A. Young came to birders’ attention with his enthusiasm for finches and as the go-to guy for birders who needed their recordings of Red Crossbills identified by type (which is how Lillian met him!). He is the President and Founder of the Finch Research Network (FiRN), currently teaches Intro to Birding and Nature Observation classes for Cornell University, is the Board Chair at The Wetland Trust, and apparently also has a day job. Together they’ve appeared on a number of podcasts promoting The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada, which is a good way to get a taste of the book’s contents and witness the effectiveness of their new collaboration.*

I have three nitpicks. The first two are common problems, at least for me. The sans serif font used for most of the text is light and fine, making it sometimes difficult to read. Some pages appear to be printed in a gray-colored font, exacerbating the problem. Fortunately, the bold headings in black, red, and green and the text boxes on nesting and “Deeper Dives” visually interrupt and frame the text, helping the eye to focus.

The index is the second nitpick. I am glad there is an index, I only wish it was more extensive. It lists the common and scientific names of all species covered by the guide (there is also a Quick Alphabetical Index on the inside front cover). This takes up one page. But this book is so much more. It covers important concepts like irruptive movements and taxonomy and interesting topics like feeding and gardening for birds and it covers them throughout the book. I think it would be helpful to the user to have assistance locating this information via the index. On the more positive side, the Table of Contents on the very first page is excellent, listing all species accounts and other sections of the book in easy-to-read color blocks. (It’s surprising how many birding books do not include detailed tables of contents these days.)

Finally, a few words about the essays called “Quick Takes.” These essays introduce every “main breeding” finch and the sections on vagrant finches and Hawaiian Honeycreepers. Differing widely in tone and topic, they are described in the introduction as “meant to engage, make memorable, and bring to life the personality and essence of that species” (p. xii). They range from an elegant description of Black Rosy-Finch and the “harsh disconnect” on their lives wrought by climate change, to a Socrates-like questioning on “What is the essence of a Cassin’s Finch?” to an ‘interview’ with a Lawrence’s Goldfinch on its future name change (Fiddleneck Goldfinch is hinted at). I enjoyed the essays, but I found them a bit confusing till I heard Lillian talk about her intentions and writing process on the podcasts. (To my mind, “Quick Notes” means bullet points or a 2-sentence paragraph.) The point of view is confusing, it switches from third person to first person (occasionally in the same essay), to seemingly the perspective of the finch itself. Some of this made much more sense once I learned that Lillian Stokes wrote the essays, and it was her first-person point of view coming forth. This information is in the introduction, but, as we all know, introductions are seldom read thoroughly (even by me) and a bit more clarification for each “Quick Take” would have been helpful.

The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada is a smartly organized, extremely informative, beautifully designed guide to a family of birds that are both common and special. It is a challenging family. I can’t think of another North American bird family that contains so many species that are out-of-the-ordinary, following irruptive or nomadic migration cycles, vocalizing in so many geographic-specific ways, featuring evolutionary developments that blow the mind. Lillian Stokes and Matthew Young not only describe all of this in ways we can understand, they encourage informed observation of our finches, particularly boreal finches, participation in citizen science projects and create excitement about future irruptions and citizen science research. The 2024-25 Winter Forecast says Evening Grosbeaks might be coming south this winter. I really hope so. The first time I saw an Evening Grosbeak, in Sullivan County, New York in January 2008, I could only marvel at its magnificence. Seeing the finch again, my joy will be tempered by their scarily decreasing numbers but my appreciation will be deepened by knowing that I’m listening to a type 3 call (I might even record it to make sure), that Evening Grosbeaks love spruceworm larvae but will also eat a variety of tree seeds and fruits and snow for hydration, and that they may be monogamous, but we’re not totally sure. I may even see an Evening Grosbeak that has been banded by the Finch Research Network. Buy this book to identify the finches, keep reading it and its cited resources to learn how you can contribute to their future.

My Life Evening Grosbeak, © 2008, Donna L. Schulman

* Podcasts:

ABA Podcast, Sept. 19th, 2024, https://www.aba.org/08-38-a-field-guide-to-finches-with-lillian-stokes-and-matt-young/;

Bird Nerd Book Club, featuring our own Hannah Buschert, https://www.gobirdingpodcast.com/copy-of-hannah-and-erik-go-birding

Life List, Sept. 11th, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/deep-dives-and-easter-eggs-in-the-new-stokes-finch-guide/

The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada

by Lillian Q. Stokes and Matthew A. Young

Little, Brown, & Co., Sept. 2024, 352pp.

ISBN-10:0316419931; ISBN-13:9780316419932

$21.99 paper; $14.99 ebook

Leave a Comment