New Year’s resolutions from birding friends are starting to trickle in as I write this review. It is the last day of 2015, time to select the bird of the year past and set goals for the bright open future, when everything is new again. Big years, little-big years, surpassing your state list, trouncing your best friend’s state list, inching up on the eBird top 100 (well, no one says that, but you know people are thinking it). We are a list and number oriented culture and there’s nothing wrong with that, but sometimes I feel the urge to aspire for more. My usual birding resolution, to add to my ABA list, is worthless; I’m too easily distracted by the seasons and trips to non-ABA shores. Maybe this is the year I should simply resolve to be a better birder.

And so, I turn to Better Birding: Tips, Tools & Concepts for the Field, the new book by George L. Armistead and Brian L. Sullivan. This is a very different book from what I expected, less of a handbook and more of a comprehensive identification text on 24 groups of birds, presented in words and photographs. The idea, as spelled out in the excellent Introduction, is that “good birders” don’t use only field guides to identify a bird; they “know” the bird. And “knowing” a bird is not, as many of us like to think, the Zen state of a few gifted individuals born with bird lore in their DNA. It’s the result of hours of study, in and out of the field, mostly in the field. It’s the process of using knowledge of natural history, habitat, distribution, behavior, and, yes, taxonomy, combined with specifics of adult and juvenile plumage and vocalization to identify a bird, often to the subspecies. The process is called “Wide-angle birding: Be the bird, see the bird.”

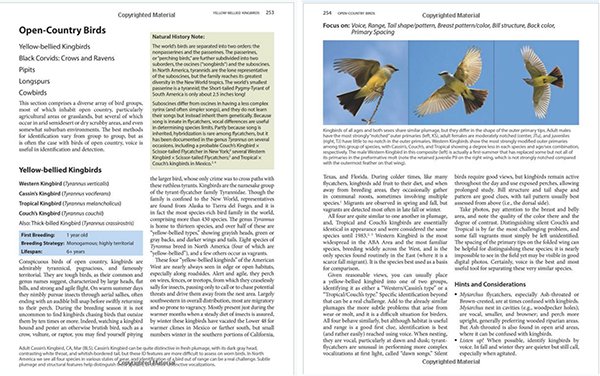

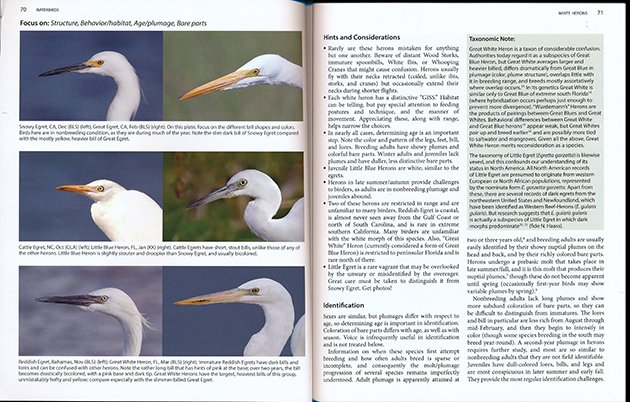

The 24 groups of birds are organized into nine broad categories—Waterbirds, Coastal Birds, Seabirds, Large Shorebirds, Skulkers, Birds of Forest and Edge, Aerial Insectivores, Night Birds, Open-Country Birds. To give you some idea of the species covered, here are some specifics: Loons–Red-throated, Pacific, Arctic, Common, Yellow-billed; White Herons–Snowy, Great, Cattle, Reddish Egrets, Little Blue and “Great White” Herons, and Little Egret; Small Wrens– House, Winter, Pacific, Sedge, Marsh; Yellow-bellied Kingbirds–Western, Cassin’s, Tropical, Couch’s, Thick-billed; Black Corvids –American, Fish, Northwestern Crows, Common and Chihuahuan Raven; American Rosefinches–House, Purple, Cassin’s Finch. It seems rather random, but there is a method behind the choices, which the authors explain in the Introduction. All species are from the ABA area, and all groups must meet at least one of these criteria: (1) the group “represented a good opportunity to build core birding skills,” (2) the authors thought it was a group that needed “a refreshed treatment,” (3) the authors were intrigued by the group and wanted to present it using their unique format.

The 24 groups of birds are organized into nine broad categories—Waterbirds, Coastal Birds, Seabirds, Large Shorebirds, Skulkers, Birds of Forest and Edge, Aerial Insectivores, Night Birds, Open-Country Birds. To give you some idea of the species covered, here are some specifics: Loons–Red-throated, Pacific, Arctic, Common, Yellow-billed; White Herons–Snowy, Great, Cattle, Reddish Egrets, Little Blue and “Great White” Herons, and Little Egret; Small Wrens– House, Winter, Pacific, Sedge, Marsh; Yellow-bellied Kingbirds–Western, Cassin’s, Tropical, Couch’s, Thick-billed; Black Corvids –American, Fish, Northwestern Crows, Common and Chihuahuan Raven; American Rosefinches–House, Purple, Cassin’s Finch. It seems rather random, but there is a method behind the choices, which the authors explain in the Introduction. All species are from the ABA area, and all groups must meet at least one of these criteria: (1) the group “represented a good opportunity to build core birding skills,” (2) the authors thought it was a group that needed “a refreshed treatment,” (3) the authors were intrigued by the group and wanted to present it using their unique format.

It is an intriguing choice of species. There are no warblers here or small shorebirds or raptors, excepting Accipiters and Screech-Owls. These are bird groups that have been covered extensively by other guides. Better Birding thus fills a niche, presenting detailed discussions of bird groups that are not “sexy” enough to have their own guides, often falling through the cracks of avian publishing, but which pose identification puzzles in the field for even the most experienced birders.

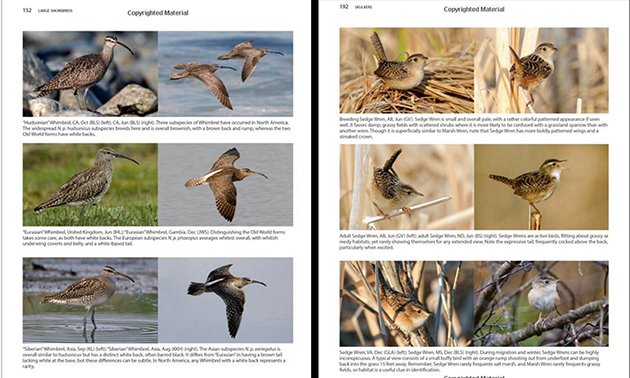

The chapter format proceeds from the general (the wide angle) to the specific (species descriptions): A lengthy essay on the bird group as a whole, discussing natural history, taxonomy, and identification challenges; “Hints and Considerations”–bulleted tips to keep in mind when observing the bird, ranging from vocalization to seasonality to the best way to structurally analyze it; “Identification”—plumage overview of all species in the group, followed by species accounts. These are extremely detailed, covering distribution, behavior, and plumage by age and gender (when relevant) and comparisons with other species in and external to the group. There are 850 photographs in Better Birding, and about 85% of them are integrated into the Identification sections, illustrating hundreds of points of identification involving structure, size, wing pattern, underwing pattern, prebasic molt, preformative molt, variability of white or buff or cinnamon on the wing, breast, or back, juvenile and adult plumages, breeding and nonbreeding plumages, similarities and exceptions to the rule. Birders interested in subspecies will be delighted by the extended analyses of plumage and habitat variations.

The two pages below, from different chapters, give you some idea of how comprehensively Better Birding covers identification. The first shows three subspecies of Whimbrel that have occurred in North America–“Hudsonian,” “Eurasian,” and “Siberian.” Each subspecies is also thoroughly described in the text. The second page depicts Winter Wren variations; it appears opposite a similar plate on Pacific Wren (identical in shape and structure, more “rufescent” in color, different vocalizations), enabling the intrepid birder to learn how to differentiate between the two recently split species (apparently, there are cases of out-of-range Winter Wrens in the west).

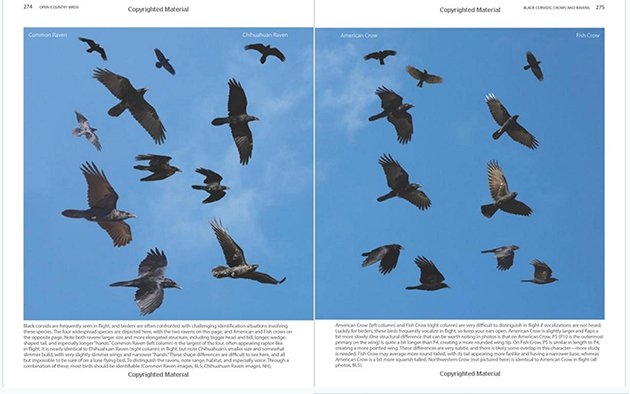

Additional information is presented in boxes and with photographs. Light blue boxes give brief facts on breeding age, strategy and lifespan. Green boxes offer Natural History and Taxonomic Notes. “Focus on….” pages present photographic lessons on differentiating similar species by structure or wing pattern or habitat or flight style–the specifics varying according to the group. Photographic flight spreads, in the now familiar Crossley Guide style, are featured for Corvids, Swifts, Atlantic Gadflies, Accipitoers–bird groups we often must identify with our necks craning up.

Each chapter concludes with References, a bibliographic listing of the books, articles, and web pages cited in the text. There is no end-of-book list of resources, which reflects, I think, an assumption that the birder using this book is already familiar with the more general birding books and magazines. The book’s Index admirably includes concepts presented in the Introduction, as well as listings of species by common and scientific name and by group name. It’s one of the best indexes I’ve seen in a long time. Looking for Kittlitz’s Murrelet? You can find it indexed under “Kittlitz’s Murrelet,” “Murrelet.” and “Brachyramphus.” Want a photograph of Kittlitz’s Murrelet? Just go to the boldfaced page number.

To an intermediate-level birder like me, the material in Better Birding–highly focused, detailed, based on the latest research and years of field experience– is daunting, but also fascinating. Authors George L. Armistead and Brian L. Sullivan are birders as well as writers, researchers, and organizational administrators, and this makes a big difference. George was a tour leader for Field Guides, Inc. and is currently events coordinator for the American Birding Association and a research associate in the Ornithology Department at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. He also wrote the newly published American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Pennsylvania (Scott & Nix). (Here is the disclosure part, where I state that I have traveled with George in both his Field Guides role and his ABA roles and consider him a birding friend.) Brian Sullivan is currently eBird program co-director and photographic editor for Birds of North America Online at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. He has co-authored The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors and the East and West Coast editions of Offshore Sea Life ID Guide (Princeton Univ. Press, 2015), and has also written articles on eBird and bird identification.

George is a natural teacher and I’m betting that Brian is one too. The book is designed to present information on several levels; you can read the easily accessible “Hints and considerations” and “Focus on” sections, or you can delve into the denser species accounts. The writing style is friendly, expansive, scientifically informed, and draws distinctive pictures of each species. Le Conte’s Sparrows “look particularly dapper” from September to March; American Rosefinches “are rabid songsters”; Pelagic Cormorant is “potbellied and long tailed, possessing a very skinny neck and an equally small, fine head.” It is very difficult to write a book like this without becoming pedantic and repetitive (how many ways can you describe a bird’s shape or wingbeat?). One of the ways in which Better Birding succeeds is by never forgetting that it is teaching skills, and consistently integrating suggestions on how to learn the content better into the descriptive text.

The Introduction covers the purpose of the book, the definition of “wide-angle birding,” and discusses the basics of becoming a “Good Birder.” Much of the latter material–distribution, habitat, using eBird, molt, taxonomy–is familiar, but worth reading for the authors’ integrative treatment. I particularly liked the section on Recordings and Playback, which goes into great detail about how to think through using playback in a specific situation and, in the end cautions that “going out into the field and using playback with no experience would be almost like getting behind the wheel of a car for the first time and pulling out onto the highway” (p. 20). I’m also happy that there are sections on Birding Mentors and Why Birding is Cool. Mentorship is an essential part of the birding experience, and it needs to be encouraged. And, while I know birding is cool, it’s always good to see these words validated in print.

The underlying thesis of Better Birding is that by learning to identify these 24 specific groups of birds, you will learn birding concepts and skills that can be applied to any and all observations of birds, and you will then be a better birder. Interestingly, the concept of a “good birder” is defined in the Introduction as a birder who is “(a) well versed in the habits, range, seasonal occurrence, and identification of birds; (b) good at finding birds; and (c) skilled at recording information about them” (p. 12). So, while this book will clearly help me become a better birder for part (a), I still have a lot more to learn for improvement in parts (b) and (c). Luckily, I have a copy of How to Be a Better Birder by Derek Lovitch (2012), also published by Princeton University Press, which covers the bird finding part–understanding weather, habitat, and geography, using radar. The two books together make a great combination. All we need is a PUP book on bird documentation, which will hopefully include sketching and notes as well as Everything You Can Do with eBird.

Better Birding: Tips, Tools & Concepts for the Field is an excellent book for intermediate and advanced birders who enjoy the challenge of identification, who thrive on learning while they bird, and who want to broaden their in-depth knowledge of species overlooked or misidentified by other birders. It is also a great resource for birders who love going out and finding rarities, because you can’t identify the rarity if you don’t know the common. I would not recommend the book to beginning birders; the content has great potential for newbie intimidation and there is also an assumption that the reader is familiar with avian anatomical and basic scientific terms. I myself will be starting with the chapters on Marsh Sparrows. A small step but a challenging one, a learning curve that might take months, maybe years. I’ll know I’m a better birder when I can look at a skulky, buff and brown sparrow through the reeds and immediately say, “Aha! Le Conte’s Sparrow!”

————————-

Better Birding: Tips, Tools & Concepts for the Field

By George L. Armistead & Brian L. Sullivan.

Princeton Univ. Press; December, 2015.

360 pages; 850 color photos. 4 maps; 0.8 x 7.5 x 9.5 inches.

ISBN-10: 0691129665; ISBN-13: 978-0691129662.

Paperback: $29.95 (available at a discount from the usual suspects)

Kindle version: $20.99; also available from the Intel Education Study eBook store, if you would like to use this title in the classroom.

Leave a Comment