Rick Wright is a well-known birding tour guide, author, blogger, and general wordsmith. He was a Beat Writer here on 10,000 Birds for awhile, contributing wonderful pieces, and we miss him a great deal. Fortunately, he agreed to contribute this guest post on a topic he is eminently suited to write about – the intersection of birds and words.

It’s one of the stories every birder knows.

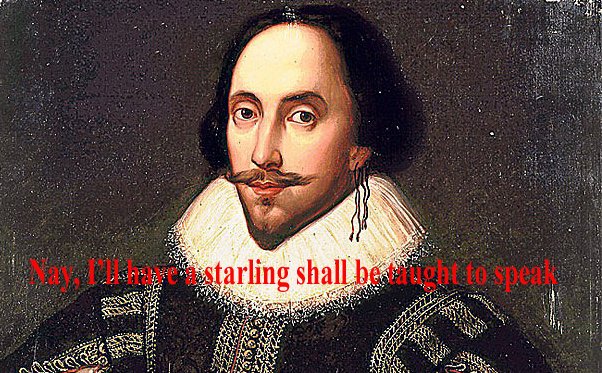

In the late nineteenth century, Eugene Schieffelin, a wealthy New York drug manufacturer, resolved to introduce to North America every species of bird mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare.

Those wacky pharmacists.

Most of the birds Schieffelin released died a miserable death on the streets of New York City, but a few survived and thrived—among them his beloved European Starlings. Our native bluebirds, woodpeckers, owls, and flycatchers have paid the price of bardophilia ever since.

There’s an elegance to this story and a captivating weirdness, and we relish the retelling of it even a century and a quarter later. Only thing is, I’m not sure it’s true.

Yes, it’s told and retold in even the most authoritative handbooks—but never, not once, with a citation to a contemporary primary source. The account in Christopher Lever’s Naturalized Birds of the World, for example, is full of detail,but neither of the earlier works he claims to base it on — Phillips’s Wild Birds Introduced or Transplanted of 1928 and Chapman’s 1895 Handbook — says anything about Shakespeare. Eaton’s 1914 Birds of New York identifies Schieffelin by name as the “liberator” of the Central Park starlings, but again, without any indication of his literary motivations. It is more than odd that such a piquant detail should have been left out in these early accounts—only to appear long after Schieffelin and his contemporaries were dead.

Schieffelin was long a leading figure in the American Acclimatization Society, a bizarre group of meddlers based in New York City. One occasionally hears that the AAS, too, was motivated by the Shakespearian principle, but in fact, the Society’s articles of incorporation adduce only “usefulness” and “interest” as the criteria for introduction. With a Horatian eye to their capacity to delight and to profit, the Society’s introductions over the years included everything from brook trout to Java finches, neither of which, if memory serves, ever trod the boards at the Globe.

Like others of his class and time, Schieffelin may well have been a Shakespeare fan. And there’s no doubt that he introduced the starlings whose descendants are right this very moment pacing off our backyard. But the link between those circumstances? Unknown, and probably non-existent.

Unless, of course, someone can find the smoking historical gun. Is there any documentation, from Schieffelin or his contemporaries, that the release of starlings in Central Park in 1890 was inspired by a line in Henry IV? I’d be happy to know about it.

…

Here at 10,000 Birds 20 July – 26 July is Invasive Species Week. We use the term “Invasive Species” in the broadest sense, to encompass those invasive species that have expanded beyond their historical ranges under their own power, by deliberate introduction, or by unintentional introduction. The sheer number of species that have been shuffled around on our big earth is impressive, though we will be dealing with the smaller sample size of invasive avians and other invasives that effect avians. Nonetheless, this week will be chock full of invasive species. So batten down the hatches, strap on your helmet, and prepare to be invaded! To access the entire week’s worth of content just click here.

Here at 10,000 Birds 20 July – 26 July is Invasive Species Week. We use the term “Invasive Species” in the broadest sense, to encompass those invasive species that have expanded beyond their historical ranges under their own power, by deliberate introduction, or by unintentional introduction. The sheer number of species that have been shuffled around on our big earth is impressive, though we will be dealing with the smaller sample size of invasive avians and other invasives that effect avians. Nonetheless, this week will be chock full of invasive species. So batten down the hatches, strap on your helmet, and prepare to be invaded! To access the entire week’s worth of content just click here.

Of course Shakespeare will have mentioned those bird species in his plays that people were familiar with, and these would also be the species Acclimatization Societies would introduce to North America. Simply comparing the species introduced to America with those mentioned by Shakespeare will thus be of little help.

A paper by Lauren Fugate and John MacNeill Miller implicates Edwin Way Teale as the author of the Shakespeare canard: https://read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/13/2/301/234995/Shakespeare-s-StarlingsLiterary-History-and-the And see https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/11/science/starlings-birds-shakespeare.html