In 1942, a shepherd from the Ural Mountains, Vasily Zaytsev, then a soldier in the Red Army, found himself on the front lines of the Battle of Stalingrad. Zaytsev had impressive marksmanship skills, which is why he was soon transferred to the sniper division. At the same time, at the western bank of the Volga River corpses piled ever higher… or so starts the plot of the Jean-Jacques Annaud’s movie Enemy at the Gates, with Jude Law as young Zaytsev.

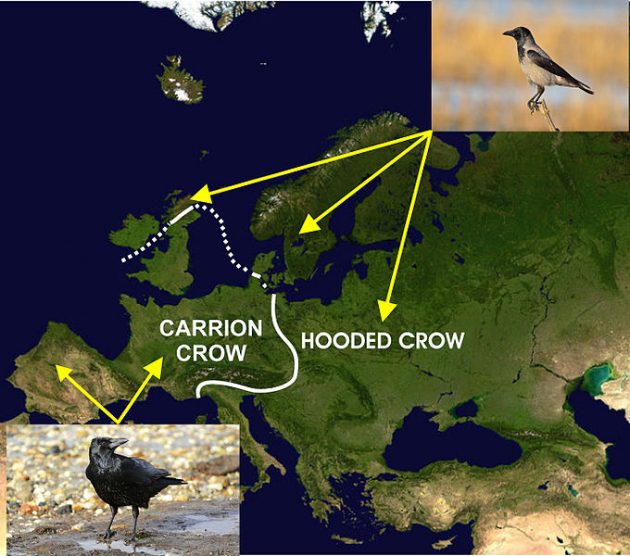

Yet, something was wrong with that picture. Something was very wrong. Just imagine a family excursion to Yellowstone to photograph grazing herds of elephants – equally wrong. Was the 68 million budget too short for a consultant-naturalist? E.g. someone capable of telling the CGI masterminds that the crows at the corpses couldn’t be the Carrion Crows of Western, but the Hooded Crows of Eastern Europe? Or did the production have so little respect for their viewers that they just assumed no one would ever notice?

I do count, write and eBird all crow species I encounter, but, I admit, without much excitement. True, I do not pay much attention to crows. Yet, just like any other European birder, I do know where the Carrion Crow lives, and where it doesn’t. Stalingrad (from 1961: Volgograd) is way out of their range.

Map by Wikipedia

Map by Wikipedia

When I started to bird, sometime in the last millennium, the common knowledge was that there were about 8,500 species of birds in the World (by some evolutionary miracle, nowadays we have 2,000 more). And the only birds known to actually attack humans, not just try to scare them with screeching and low flights, but to establish a full contact in protection of their offspring, were owls.

Therefore you can imagine my suspicion when I started to receive calls from various journalists to comment on cases of Hooded Crows attacking people. Such news would usually end up in tabloids with some title reference to Hitchcock’s The Birds. Slowly, I started to hate that movie. Since the same story is repeated year after year from several parts of the city (and spreading), I had to take it seriously.

The explanation is simple enough, fully developed chicks would take their first flight, get scared and hide in some bush, waiting for their parents to feed and encourage them. And protect them, too. It only lasts for a day or two before they take flight themselves, but people do not respond with much understanding. Usually they expect some service to come, catch and remove the pesky birds.

The panicky human parents are the worst kind. Scared for their offspring, they demand more radical measures. I would advise them to wear a hat, or protect a child with an umbrella for those 20 metres, but to no avail. I tried suggesting that they explain to their kids that the parent-birds are protecting their children just at their mum or dad would (I think that from the child’s point of view, such explanation should sound perfectly reasonable), but they were never happy and sometimes were angry at me because I would not came there to deal with those naughty birds personally.

As sick of mankind as I can get, I was still curious of crow aggressive behaviour. What is it they actually do? While I expect owls to use their claws to draw blood, crows don’t have much in that regards and I presume that they peck people with their beaks. But I have never seen it. And when a teacher called me for an advice what to do – they have some angry birds next to the school, I calmed her by saying that it will last only a day or two, but also sat in my car and went there to observe the behaviour.

There were very few pedestrians to provoke the birds. I didn’t stay there for long, either: after a while, I realised how I must look – a 50 something bald guy holding binoculars in a car parked next to a school yard – and despite the fact that due to a nation-wide flood emergency all schools were closed, I left soon after that realisation. Also, there were no crows to be heard or seen.

Leave a Comment