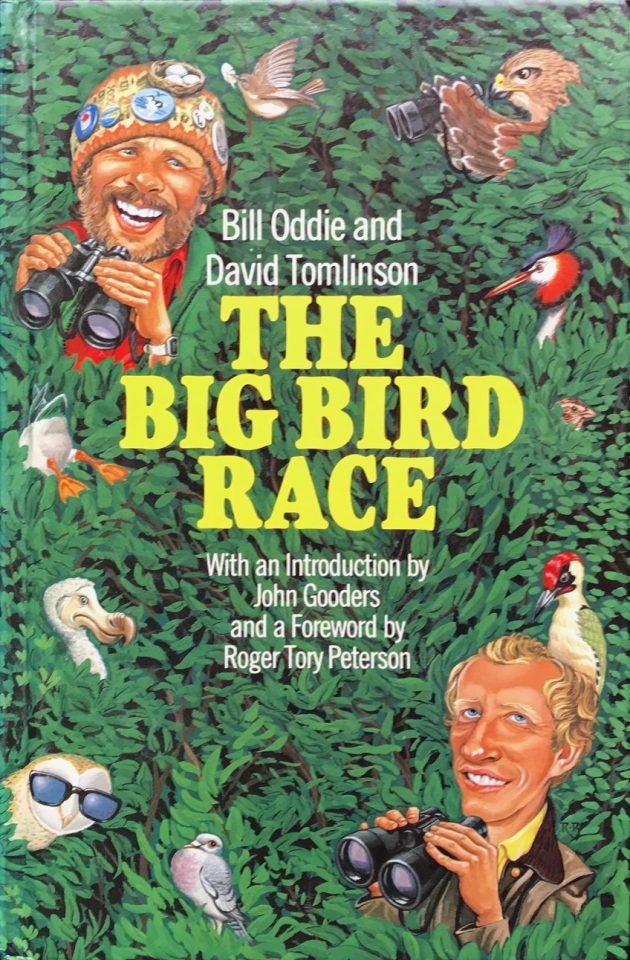

In my younger days I was very keen on what is generally known as Big Day Birding, or trying to see as many species of birds as possible in one day. In 1983 I co-wrote a book about a one-day, 24-hour competitive birdwatch that I took part in. Called The Big Bird Race, it tells the story of how my team, representing Country Life magazine, recorded 155 species in 24 hours in East Anglia (Suffolk and Norfolk). Our opponents were a team representing the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society (ffPS). They scored 144. Bill Oddie (a British comedian, television personality and keen birder) was a member of the ffPS team, and he was my co-author of The Big Bird Race. Though long out of print, it’s not difficult to pick up copies of the book from secondhand book shops for a modest sum. Though I say it myself, it still makes an amusing read.

I’ve done a number of big days since, most notably in Kenya in 1986. This wasn’t a mere 24-hour bird race, but a 48-hour event, and was filmed by the BBC for a programme called The Great Safari Bird Race. My team scored a mind-blowing 292 species on the first day, and finished 24 hours later on 442. Sounds impressive, but we came third overall, with the winning team comfortably exceeding 500 species. To achieve our score, we started at dawn in Kakamega Forest in Western Kenya, from where we flew to the Rift Valley, then on to the Indian Ocean coast at Malindi. The following day we travelled through Tsavo National Park before finishing in Nairobi. It was as exhausting as it sounds, but terrific fun.

You may note that the events took place a considerably long time ago, so when my birding pal Andrew Goodall suggested that we should spend a day in May trying to find as many species as possible in our local patch, I was keen, but with reservations. We both agreed on a 3.30am start, but I suggested that we should stop in the middle of the day for lunch and a snooze, then start again at around 3.30am. Andrew readily agreed. I also suggested that we should also split the driving, with one of us driving in the morning, the other in the afternoon. It was what you might call a Gentlemen’s Big Day, or more accurately, an Old Gentlemen’s Big Day. It was also strictly non competitive, with no rules to abide by, such as both of us hearing or seeing each bird.

So it was that at 3.30am on the morning of Saturday, 18 May, the two of us were to be seen listening for birds at our local nature reserve, Hopton Fen (a wet and reedy valley fen). Actually we couldn’t be seen, as it was still too dark, but we did hear a couple of birds to start the day: Tawny Owl and Cetti’s Warbler. Our next stop was a pig field where Andrew had heard Stone Curlews a couple of weeks before, but on this cool and misty morning there wasn’t a sound to be heard.

A roding Woodcock at dawn

The secret of finding as many birds as possible on a day like this is to visit as many different habitats as possible. We arrived at our next site, a forest clearing, at 4am, just as dawn was breaking. We’d hardly got out of the car when we heard our target bird, a churring Nightjar, so wasted no time in setting off for our next destination, Knettishall Heath. It was still quite dark when we arrived, but a little light was seeping into the eastern sky, and birds were starting to sing. Much to our surprise, the first bird we heard was another Nightjar, and this was soon followed by our target species, a roding Woodcock. A Cuckoo called continuously from not far away.

Stonechat, a heathland specialist. We only saw one during the day

The dawn chorus is at its best in the first hour after sunrise, so we added common birds quickly to our growing list. Wren, Blackbird, Song Thrush, Robin, Garden Warbler, Blackcap, Goldcrest, Treecreeper, Chiffchaff were all noted by 4.30, and we soon managed to add two more tricky species: Stonechat and Willow Warbler. We had enlisted the aid of modern technology, with the Merlin app on our phones coming up with the Stonechat before we saw it.

Stake-outs are important time-savers on days such as this, and our next target bird – Stone Curlew – was a bird we had a reliable site for, and one we could view at long range from a public footpath. The curlews didn’t disappoint us, either, while I doubt if they saw us. Stone Curlews are rare and special birds of our area, and one not to be disturbed, so a distant view was more than satisfactory. Incidentally, I didn’t carry a camera during the day, so the photographs illustrating this piece are stock shots from my photo library, and were not taken on the day.

Stone Curlew. A pair, visible from a public footpath, were among our best birds of the day

We then had our longest drive of the day, to a wetland reserve in Norfolk, Dickleburgh Moor. We were operating on a self-restricted radius of 17km from Andrew’s house, and Dickleburgh is almost exactly that distance. After listening and looking for birds in woodland, this was easy birding, and a host of species fell quickly. There was a good variety of ducks, including Tufted, Gadwall and Shoveler, plus our first waders of the day. These included nesting Lapwings, while we also added Little Ringed Plover (pictured below), Ringed Plover (four migrants, pausing briefly before heading north), and a fine Black-tailed Godwit in full breeding plumage. The latter was a bonus bird that we hadn’t anticipated.

Dickleburgh added Common Tern to the list

There were nesting Black-headed Gulls here, along with loafing Lesser Black-backed and Herring Gulls, while we were delighted to see a passing pair of Common Terns, along with several Little Egrets. We added a few small birds, too, including Mistle Thrush and Sedge Warbler. The score was now well over 70 species, so we were doing as well as expected. The only downside was the weather, which remained stubbornly cold (12degC) and grey.

Little Egrets are recent colonists of England: we didn’t seen any back in the 1980s

A check of the churchyard at Dickleburgh drew a disappointing blank on Spotted Flycatcher, and our next site, Redgrave Lake (an extensive ornamental lake, viewed from the road) also failed to add anything to the list. However, at Redgrave and Lopham Fen, another nature reserve, we were delighted to watch Hobbies hawking for dragonflies, with as many as five birds in view at once. This fen has breeding Marsh Harriers, and we saw at least three different birds, while Cuckoos called close by.

We stopped at 1pm for our afternoon break, with the score on 77. By now the sun had finally broken through, so I was able to enjoy the luxury of a post-lunch, 30-minute snooze in the sun to recharge my personal batteries. (I heard another Cuckoo from the garden). At 3.30pm we were off again, this time with me at the wheel of my two-seater, open-topped car. Convertible cars are great for birdwatching, as not only do you have much better vision, but you can also hear birds. Our open-top motoring allowed the addition of our first Red Kite of the day, a bird that I was surprised it took so long to find.

The two wetlands we visited in the afternoon (Micklemere and Great Livermere) added a few more birds to the list, including Oystercatcher, Shelduck, Pochard and Garganey. The latter was a drake, hiding in the long grass, that I glimpsed but failed to get Andrew onto. A quick check at Pakenham Water Mill produced an instant Grey Wagtail, a pleasing find, as these elegant wagtails are localised breeding birds in this part of Suffolk.

A localised breeding birds in Suffolk, finding a Grey Wagtail is always pleasing

Shelduck are mainly coastal breeders, but we have a good population locally

We enjoyed a gloriously sunny evening, a complete contrast to earlier in the day, but adding new birds to the list was becoming difficult, as there were now so few possibilities. At Brettenham Heath National Nature Reserve we heard Curlews, and enjoyed a great view of a singing Woodlark. We continued until well after sunset, but both Little Owl and Barn Owl eluded us, as did Grey Partridge. Our final score was a satisfactory 88 species, for which we had walked or driven a grand total of 130 miles. According to my phone, I’d walked close to 21,000 steps. It had been an excellent day, and while there were no real surprises, it was a delight to hear singing Cuckoos at nearly every site we visited. Whether it would be possible to notch up a hundred species in a day in our area is debatable, but with the experience of this year’s Big Day behind us, it’s likely to be our target next year.

The fun of the chase – you capture it well! Interesting for me to read: you call the stonechat a heathland specialist while it is a common farmland bird here in Portugal.