An unfortunate side effect of birding in the developing world, is the amount of habitat destruction you are likely to see. Michoacán has such wonderful forests — I just wish I didn’t have to witness so many being cut down.

A few months ago, images made their way around social media here promoting the idea that each person plant one tree. One tree! That would, of course, be better than nothing. But one tree isn’t going to reverse the damage occuring in Latin America. That is why my tiny yard, once a vacant brushy lot, now hosts some 12 trees or tree equivalents (including bamboo and banana thickets and 4-story-tall vines). And, since I have control over a one-acre church lot, I have been learning about a new practice: afforestation.

Afforestation is not a typo for the better known reforestation, which is an attempt to restore destroyed forest areas. Afforestation is the creation of a forest in a site that was not previously forested. It involves some unique challenges, especially in a wet/dry fire-prone biome such as the Mexican highlands.

I started afforesting our church lot in 2016, just after we were able to fence it. (The neighbors had advised me, from experience, that planting trees without excluding the local free-ranging livestock would be an exercise in futility: first challenge overcome.) My 2016 efforts began with a generous gift of 43 seedlings from a local botanical garden, representing just the sort of diversity that most reforestation efforts lack. Alas, only 12 plants remain from that season, victims of my inexperienced care. Some did not survive a spotty first rainy season. Others eventually died, and all were seriously affected, by the second great challenge to afforesting my lot: brushfires!

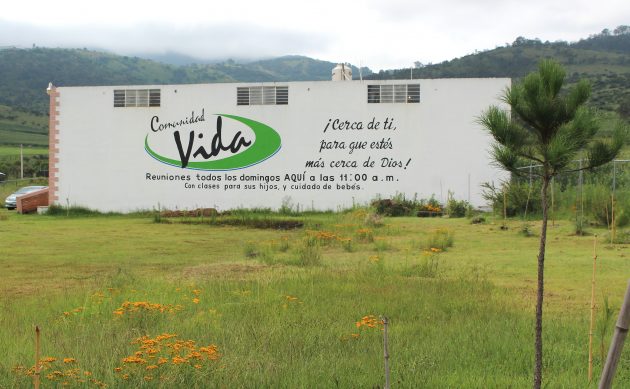

Our church lot, part of which you can see below in its improved form, is gradually sloping, with a very rocky subsoil. The second photo shows its natural condition, with waist-high summer grass and scattered small huizache (sweet acacia, Vachellia farnesiana) trees. It is almost a bog during our summer rains, but is bone dry from December through May. Late spring brushfires are regular occurrences.

Our local trees are highly adapted to low-density fires. Once the trees are tall enough, and shade lessens the growth of grass, most trees can survive brushfires. But getting from grasslands to forest is a very tricky proposition. Each of the following trees are from that original group of seedlings; they have all survived 3 brushfires, and only the Ocote Pine has yet made it beyond waist-high:

This Michoacán Pine is one year younger, and has survived one less brushfire. It is chest -high, and is one happy pine! As its name suggests, the Michoacán Pine is singularly adapted to our conditions, and I have since planted 15 more, 13 of which are still with me. (I’ve learned a lot since that first year.)

This oak was my first success with collected acorns. It is now in its third year, has survived only one minor brush fire, and this year has grown taller than my 5-year oaks. (There are a pair of this year’s seedlings at the top of this article.)

For a plant-lover like me, it is hard to accept that grass is the enemy. It is even harder to accept that all the lovely flowers that grow with that grass must go, in order to give my trees a fighting chance. I trim around the milkweeds, and perennial marigolds, and bog orchids when I can. The wild onions are too numerous, so I must trim them and smell like onions. But someday, when the trees are tall enough, I hope to leave them all.

Alas, this is what I must trim.

I keep my eyes on the prize: a small patch of forest with lots of diversity for wildlife. I have successfully started, from wild-collected seeds and cuttings, food sources for birds such as Coral Trees, Cassias, Chokecherries, and lots of Oaks. I now protect the lots Huizaches, which shelter self-sown fruiting plants such as Granjenos and Prickly Pears. Wild Grapes are sprouting in a pot in my yard as I write.

The Colorín (Coral Tree) seedlings are doing well this year.

While the Colorines grow, sages are keeping our Broad-billed Hummingbirds happy.

I have also lost some weight since I decided to be personally responsible for cutting the grass on a half-acre of land. It’s a real win-win!

Afforestation is, at least here in Michoacán, a definite long-term project. But it is one real way to help turn the tide back on the losses we see around us.

We like plants ,Colorines grow, sages are keeping our Broad-billed Hummingbirds happy.

North Cardinal is my favourite bird.