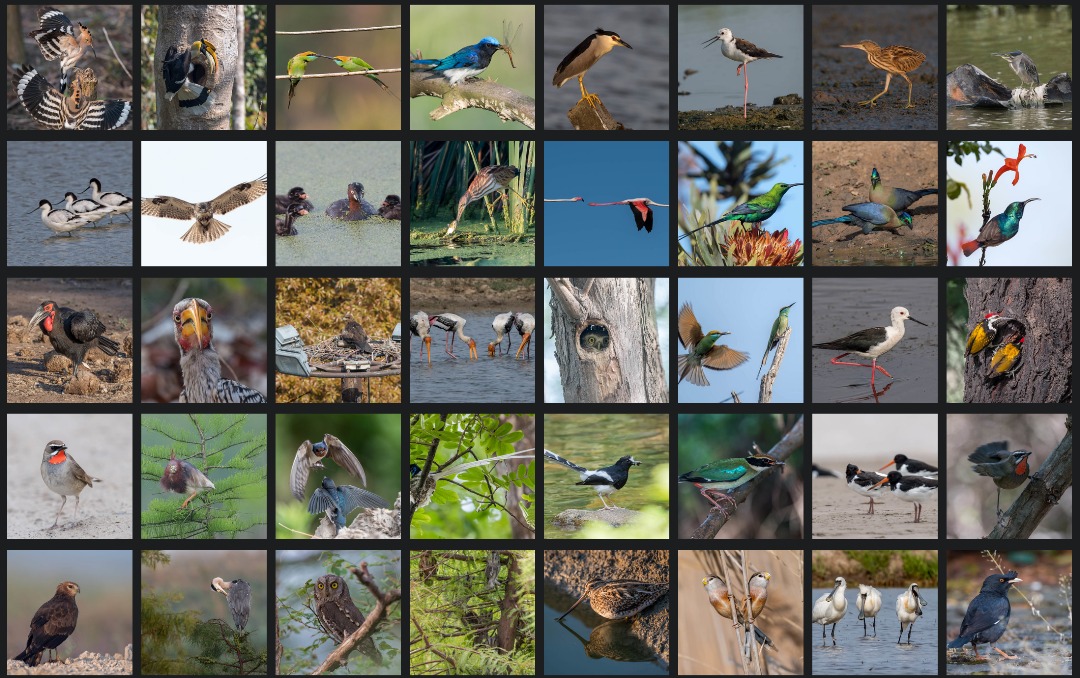

There are identification bird books with photographs and there are identification guides with illustrations. Which one is the best? And why? Our beat writers, opiniated lot as they are, have chimed in. The answer to this very important question has been composed out of their pros and cons. Undoubtedly, a new generation of guidebooks will be based on this blog post’s outcome.

An identification guide usually has pictures, and we will not tell you that “the descriptions are more important bla bla bla” – we are a visual species. Faced with an identification challenge, normal people would find the family in the field guide and use the illustrations to narrow down the selection, then browse the written descriptions to finalise the identification. The level of detail presented in the written descriptions helps tremendously for very similar species such as nightjars, larks, and waders. But it’s not the Holy Grail.

So, we like to look at pictures of birds to try and identify them and most books have used illustrations for this purpose. More recently, with the advent of digital photography more and more photographic images have become available and consequently, more photographic bird identification books haven entered the market. While there’s broad agreement that the illustrated and photographic guides are complementary, some birds are near impossible to photograph well enough to be published in a guide. To identify the Band-rumped Swift you will need to show the bird in a way that shows both head pattern and rump, so you need it in a very specific position. This will take an enormous amount of trial and error, which will prove close to impossible for very rare species. It’s much easier to illustrate the identification pointers in a plate and elaborate upon that distinction in the written description. However, a photo shows a very realistic depiction of the species; each has its share of advantages. Good photographs of swifts are very difficult to take which favours illustrations too.

The downside of photographs is clear for everyone with a digital camera: there are so many of them! This aspect translates itself into a rather specific problem. Take one our writers’ favourite Ayyash’s Gull Guide. Prior to becoming acquainted with Ayyash’s old-style blog Anything Larus, she did not give any attention to gulls. Many people don’t. She thinks Ayyash’s guide is going to change these attitudes. Each species has many numbered photos, and each photo is accompanied by text specific to the photo. There are quite detailed explanations of overview, taxonomy, range and identification. Although in height times width it’s a normal size, otherwise, it’s a beast of a book. Nobody carries a beast into the field.

The beastly photographic guides come into use when we want to know more about a group of birds – back home in the comfort of our living room. As a group, the beat writers have photographic guides for the passerines of Europe, terns, waders, and a deep desire for a book with the kingfishers of the world (you read it here first!). Recommended books are Shorebirds of North America (Paulson, 2005), The Shorebird Guide (O’Brien, Crossley, Karlson, 2006), Woodpeckers of the World (Gorman, 2014), Terns of North America (Cox, 2023) and The Gull Guide North America (Ayyash, 2024). For field identification, the beat writers rely on illustrated guides in combination with apps, like Merlin. The advantages of lighter weight and the complete array of possible species in a geographical area (still) wins the day.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Can we identify a difficult bird with illustrations or photographs? Which is easier? Let’s consider this wader in China. Please provide your identification in the comments and let us know the guidebook you have used.

Band-rumped Swift by Faraaz, all other illustrations by Kai.

My own preference is for illustrations in field guides with the photographic books at home. The article highlights the possibility of illustrations to highlight all the important markers in one picture. For vagrants, especially in Europe, I like to use books like Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds: Passerines (2-Volume Set). This is not a cheap book and certainly not movable.

Looks like a Long-toed Stint. ID’d without the use of any guides because I’ve memorized the field marks, as I’m still hoping to find one of these beauties here in Oregon, and I need to know how to tell it from our very similar Least Sandpiper. But, in general, for working on shorebird identification, I mostly use the old “Shorebirds – An Identification Guide” by Hayman, Marchant, and Prater (illustrations); “Shorebirds of North America – The Photographic Guide” by Paulson; and “The Shorebird Guide” by O’Brian, Crossley, and Karlson (also photos), along with a variety of regional field guides (which mostly contain illustrations).

[A quick word of advice: It might be advantageous not to label the photo of a “mystery bird” with its give-away species moniker (I only noticed this after the fact, when I downloaded the image).]??

I agree with Long-toed Stint as the ID – although, if I’m honest, I needed Hendrik’s hint. I have seen Long-toed Stint, on 3/30/2023, in an urban pond just outside of Port Blair on Ross Island (now officially named Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Dweep) in the Andaman chain of islands in the Bay of Bengal. Apology for the unnecessary brag—reason: my Andaman Island trip is important to me for many reasons—most unrelated to birding and I try to remember it whenever possible. I used Birds of India (Princeton, 2nd ed., 2012). However, my Birds of Europe (Princeton, 2nd ed., 2009) illustrations are much better than in the Birds of India guide.

I particularly like the flipflop in the foreground of the photo. Places like this are often where shorebirds are found.

The important thing is what Derek Lovitch, of the Maine Birding Center, says in his 10,000 Birds interview: use a field guide.