Bharaptur (now officially the Keoladeo Ghana National Park) was originally conceived as a duck shoot, and it still attracts ducks in great numbers today, a century and a quarter after it was first constructed. Today, of course, they find a safe sanctuary, and there hasn’t been a shoot here since 1964. The most numerous wintering species are surface-feeding (dabbling) ducks – Shoveler, Pintail and Teal. Mixed with them are lesser numbers of Gadwall and Garganey. During my last visit the Garganey drakes were just coming into full plumage, for these delightful ducks remain in eclipse throughout the winter, only gaining their spring finery in February and March. None of these ducks breed in India, for all are migrants from Siberia.

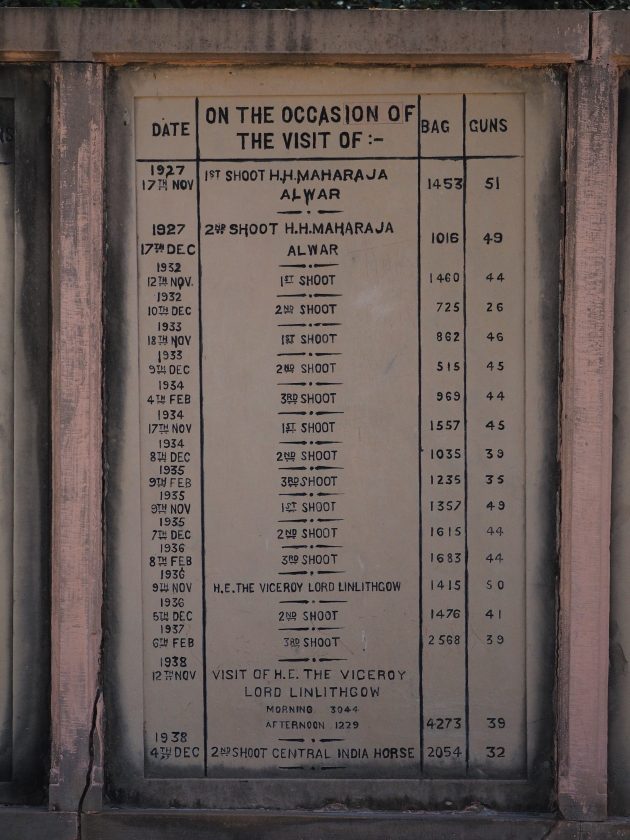

A plaque recording shoots held at Bharaptur in the last century

The most conspicuous of the local resident ducks, and the equivalent of the ubiquitous Mallard, is the Indian Spotbill. They are big, handsome birds, with a characteristic yellow tip to the beak, hence the name. They are widely distributed in tropical and eastern Asia.

Drake Pintail with a Eurasian Coot

Drake Pintails with a Little Grebe

Bottoms up – a flock of Pintails, together with Shovelers and Coots

A drake Teal

Drake Garaganey, not quite in full spring plumage

There are two other resident species of particular interest to visitors from Europe or North America – the Lesser Whistling Duck and the Cotton Pygmy Goose or Cotton Teal. They are rather unobtrusive birds that you have to look for. They’re both tropical species, with the latter enjoying the title of the smallest of the world’s wildfowl. They really are dainty little birds, and at a mere 35cm (12-14 inches) appreciably smaller than a Teal. The Lesser Whistling Duck has a similar distribution to the Cotton Teal, and is also the smallest of the Dendrocygna, the whistling duck family.

Lesser Whistling Duck, the smallest of the world’s whistlers

Whistling Duck family

A flock of Spotbills, a resident duck

There’s little in the way of deep water at Bharatpur, so diving ducks tend to be fewer in number. Black and-white Tufted Ducks are easy to find, while with a little work with a telescope you should be able to pick up a few Red-crested Pochards and the less conspicuous Ferruginous Ducks. There’s usually no problem in finding geese. Here the Greylags have pink peaks (at home in England their beaks are orange), but the most characteristic goose in the Park is the Bar-headed. This is a bird that breeds on high-altitude lakes in south-east Asia; it migrates to India for the winter by flying over the Himalayas – they have even been seen flying over Mount Everest.

Bar-headed Geese – winter visitors that migrate over the Himalayas

Sarus Cranes (above and below). There are several resident pairs in the park

Bharatpur used to be famous for its wintering flock of Siberian Cranes, but sadly the flock declined sharply during the 20th century and the last bird to be recorded on the reserve was back in 2002. But there are still cranes to be seen here in the shape of the resident Sarus Cranes. There are several pairs and you are unlikely to miss seeing them. They are the tallest of the birds to be found here, and even taller than the giant Black-necked Storks, another bird to look out for.

On my last visit I saw both Great White and Dalmatian Pelicans, two birds I know well from Greece. The latter were in full breeding condition, with improbably orange beak pouches. Painted Storks nest here in large numbers, and there were a number of lanky grey juveniles flying around. As for herons, we saw nearly every one possible, from the Grey we know so well from home to the secretive Black Bittern, a bird that you have to work for even at Bharatpur.

Marsh sandpiper – the dainty knitting-needle beak is a good field mark

Painted Snipe. This is a male

Black-winged Stilts

Red-wattled Lapwing, a common resident

There are always plenty of waders to look for, and many are obligingly tame and approachable. One of my favourites is the Painted Snipe. This is one of those birds in which the sex roles are seemingly reversed, with the females much brighter than the males. Look out, too, for Red-wattled and Grey-headed Lapwings – the former is a common resident throughout India, the latter a winter visitor. On my last visit there was a fine selection of familiar Palearctic waders feeding around the margins of the wetlands, with four sandpipers (Marsh, Green, Wood and Common), plus Greenshanks, Ruffs and Common and Spotted Redshanks, all seen in wonderful light. It is the quality of the morning and late afternoon light that adds so much to the birding experience at Bharatpur, as you see the birds so perfectly illuminated.

Oriental Honey Buzzard

Egyptian Vulture

Female Marsh Harrier

Crested Serpent Eagle

I always enjoy seeing raptors, and as you might expect, the Park has a rich variety. Marsh harriers are abundant, as this is their perfect habitat. The Spotted Eagles I saw in March would soon be heading north to breed, while the Crested Serpent Eagles and Oriental Honey Buzzards were both residents. In contrast, the two Booted Eagles were migrants. Both were dark-phase birds: In Europe I see far more pale-phase individuals. The Park used to be a great place to see vultures before their mass extinction. Today you are only likely to see Egyptian Vultures (above).

It’s quite usual to go to Bharatpur and see something you haven’t encountered before, and on my last trip my lifer of the day was Little Pratincole. There was a flock of about 40 of these dainty, almost swallow-like waders. Though it wasn’t a lifer, the Baillon’s Crake our rickshaw driver spotted in the late afternoon was also a real bonus.

Rickshaws and visitors have to be out of the park by 5.30pm, and we made it just in time. Sitting over dinner that evening, exhilarated but excited from a great day’s birding, we added up our score. Without trying particularly hard, and always giving ourselves time to enjoy each bird, we had seen 126 species. That was without using any motorised transport all day. Add in great sightings of Nilgai, the largest Asian antelope, plus Chital and Sambar deer and even a Golden Jackal and you can understand the irresistible attraction of this wonderful park.

(Author’s note. All the photographs were taken by me in the Park – some, such as the Painted Snipe and the standing Sarus Cranes, were digiscoped. They were all taken while generally bird watching rather than photographing. For the dedicated photographer the Keoladeo Ghana National Park has to be one of the easiest places in the world to photograph a wide variety of birds.)

Please take me next time you go, David, what a wonderful experience this must be. I drove past the park and had several lifers, imgaine going in…

EXCELLENT.