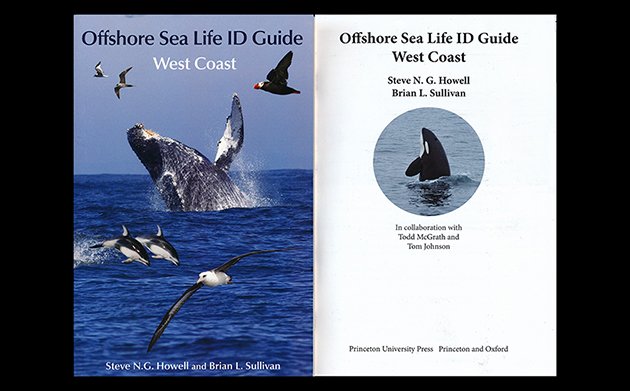

In a nice moment of serendipity, my review copy of Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: West Coast by Steve N.G. Howell and Brian L. Sullivan, in collaboration with Todd McGrath and Tom Johnson, arrived at my door the day before I was leaving for southern California. (Birds of California, the new volume in the ABA series, arrived the day I returned. Every bird book seems to be about the west coast this month!) Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: West Coast is designed to be a quick, handy resource for use on whale watching and one-day pelagic trips. I was not planning to do either, but I was going to Catalina Island with my daughter, Sarah, and her boyfriend, Todd, and the hour-long boat ride there and back sounded like an excellent opportunity to try this book out in the field.

To be fair, a trip to Catalina Island is not quite the same thing as a daylong trip in western waters. It’s a little more than an hour each way and the boat goes fast, too fast at most times to see if a shearwater bill is dark or pink or to catch sight of distant alcids. There were few periods of time when I felt secure enough to stop sea watching and consult the guide. With the boat speed what it was, and being the only birder on board, to stop watching meant I might miss an interesting bird. But, I did take many photos, and used the book, in spurts during the trip and more closely afterward, to identify three seabird species, two expected (Sooty and Black-vented Shearwaters) and one a surprise. I was impressed with book’s design and content. It made an identification process I had always found challenging into one that was rational, focused, and even fun.

This is a small book, 56 pages long. It is not quite small enough to fit into a pocket, at least not any of my pockets, but can be handily slipped into a backpack without making any noticeable weight difference. (And, at 5 by 8 inches it may be small enough to fit into some people’s pockets.) It covers seabirds and marine mammals and miscellaneous living things–creatures likely to be found on day trips from the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and California. It does not include near-shore, coastal species, like Brown Pelican, Elegant Tern, and Harbor Seal. The number of gulls and terns covered is limited to “small, ocean-going” birds. The criteria are strict and make sense, but can also lead to a certain amount of frustration. I viewed about a hundred terns on my Catalina trip, for example, but needed to wait till I got hold of a Sibley’s guide to confirm that I was seeing Elegant Terns. Rarer species are also not included, though each main chapter has a subsection on “rarer” species.

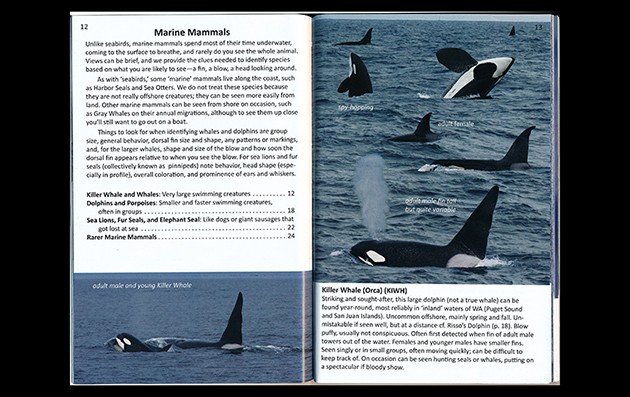

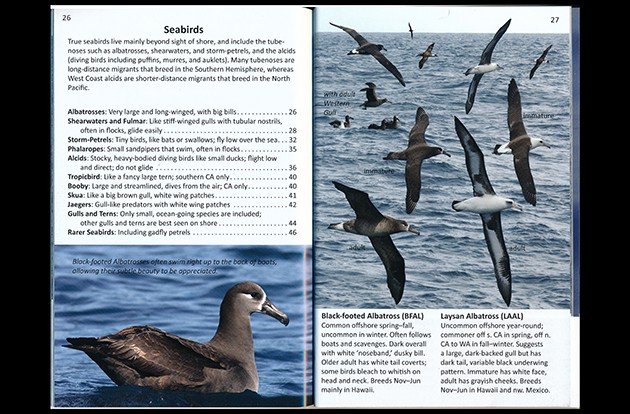

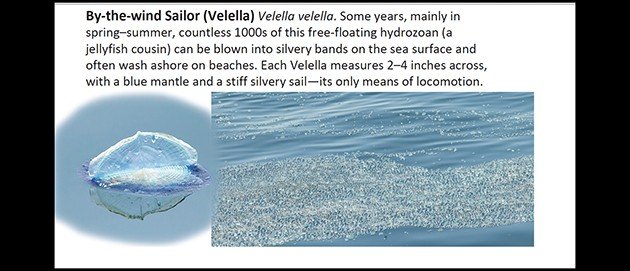

The two main chapters cover Marine Mammals (Orca; Whales; Dolphins and Porpoises; Sea Lions, Fur Seals, and Elephant Seal; Rarer Marine Mammals) and Seabirds (Albatrosses, Shearwaters and Fulmar, Strom-Petrels, Phalaropes, Alcids, Red-billed Tropicbird, Brown Booby, South Polar Skua, Jaegers, Gulls and Terns, Rarer Seabirds). That’s 22 Marine Mammal species and 43 Seabirds. An additional, five-page chapter touches on Other Sea Life–Fish, Sea Turtles, Jellyfish and Krill, Kelp, and Landbirds (the possibility of an exhausted migrating bird landing on the boat.)

Each chapter begins with a brief introduction to the group and a table of contents of subgroups that includes brief but key descriptions. Shearwaters and Fulmar are “like stiff-winged gulls, with tubular nostrils, often in flocks, glide easily”, Storm-Petrels are “tiny birds, like bats or swallows” that “fly low over the sea” and Phalaropes are “small sandpipers that swim, often in flocks.” The idea is that the observer can drill down to the correct identification. As a novice observer of seabirds, I found this method very helpful; I was concerned about differentiating shearwaters from gulls from storm-petrels, and these clues really did help with this first step.

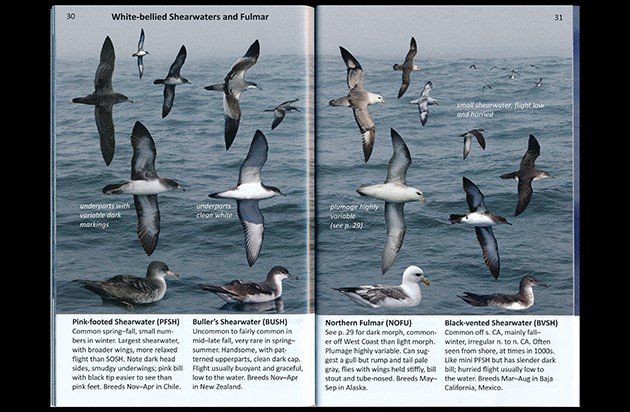

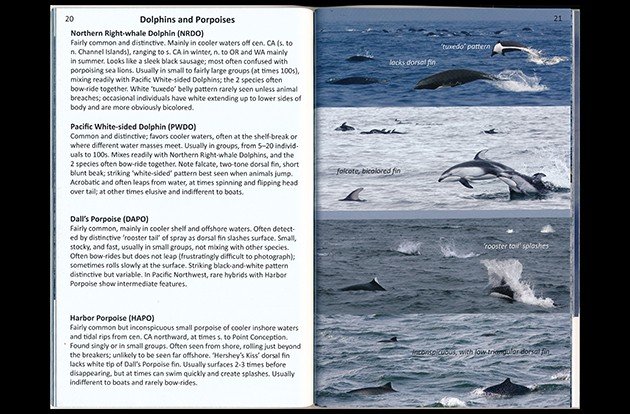

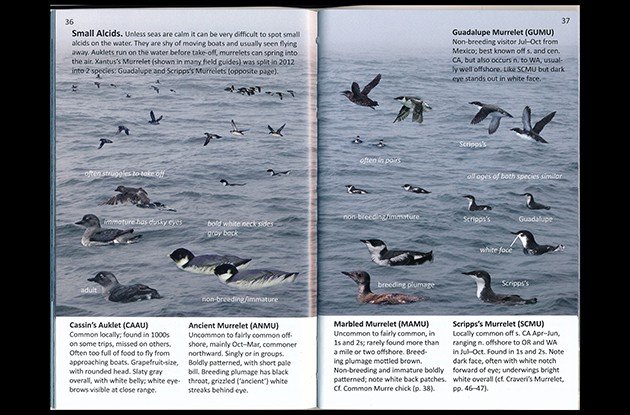

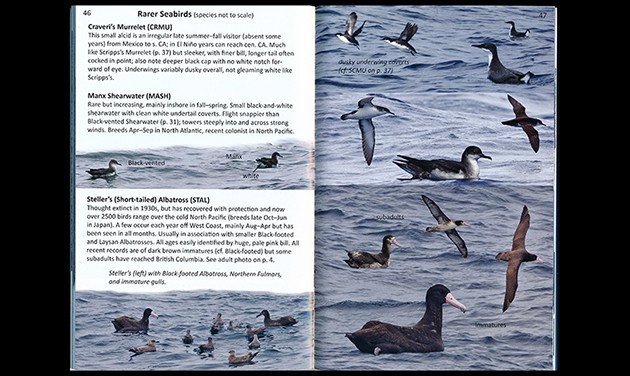

Composite group photographs and brief text descriptions present the core information, the species accounts. The composite photographs show each species swimming and flying; flying viewpoints are from underside, below, close-up, far-out, alone and in flocks; in-photo comments give important identification points and, as needed, indicate breeding and non-breeding plumage, dark and light morphs and, for sea lions, male and female/immature images.

The brief text gives common name and banding code, time of year the bird is most likely to be seen, which features of plumage, bill, flight style, and behavior to observe. Size is not always given, probably because it is often difficult to determine size at sea. I like the fact that the descriptions are mindful that the observer’s views are from a moving boat. So, it is noted that fall migrating Red Phalaropes can be mistaken for Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels, Parasitic Jaegers are apt to be closer to shore than other jaegers, Cassin’s Auklets are “often too full of food to fly from approaching boats.” I also like the way the authors give page numbers when citing other species within a species account.

This two-page spread above on ‘White-bellied Shearwaters and Fulmar’ helped me determine that I did NOT see one of my target birds, Pink-footed Shearwater, no matter how hard I tried to make a molting Sooty Shearwater, pale in the noonday sun, into one. It also helped me identify a totally unexpected bird, Buller’s Shearwater. (This is also where a photograph came in very handy. The book says nothing about photographing marine life; I highly recommend it.)

I was curious to see how the description of Buller’s compared to accounts in other guides, so I looked the bird up in Sibley’s and Peterson’s western guides. The descriptions are all similar: a graceful black-capped shearwater with clean white underparts and patterned upperparts that breeds in New Zealand and which is uncommon in U.S. western waters in the fall. Sibley’s also notes its slender, gray bill and the fact that it is usually solitary but sometimes joins other shearwaters to feed. Only the Offshore guide indicates that it is rare in spring. Petrels, Albatrosses, and Storm-Petrels of North America, Howell’s definitive book on these species, of course gives the most information, including the fact that the bird is rare to uncommon off the west coast in mid-June to July. This re-assured me that I had indeed seen a Buller’s Shearwater and that I wasn’t hallucinating the M pattern on the bird in my photograph.

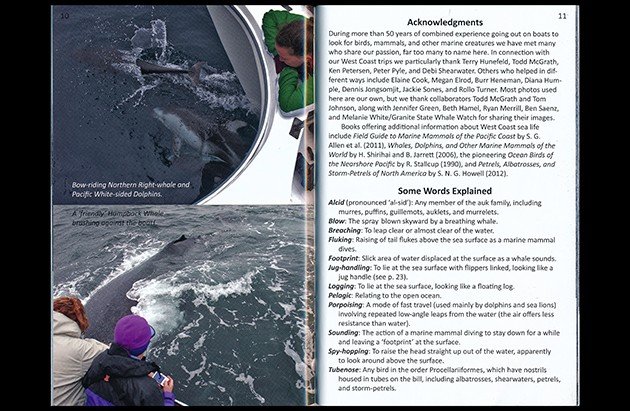

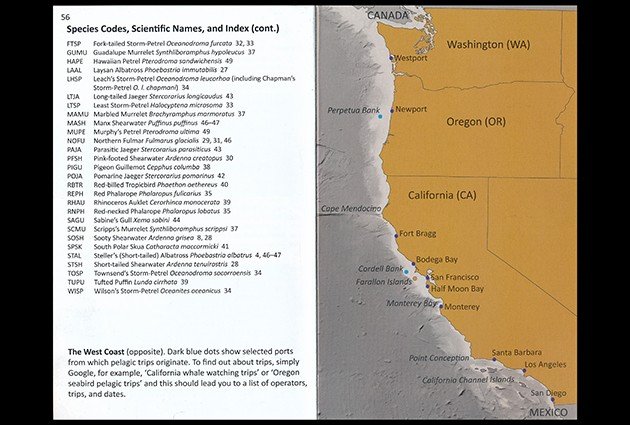

There are over 300 photographs in this small book, sharp and clear, most taken by the two authors and the two “collaborators”. Additional photographers are cited in the Acknowledgments section. This is also the page where you’ll find recommended additional print sources, followed by a brief glossary. Additional reference material includes a map of the west coast on the inside back cover and a listing that combines Species Codes, Scientific Names and Index. (Species codes are used to save space.) The Quick Page Finder on the inside front cover is helpful. In fact, for a small book, the guide contains more ways to locate species than many larger field guides. The Introduction articulates the criteria for which species are included and not included and gives a brief introduction to what to expect on a pelagic trip (unpredictability, upwelling producing an abundance of sea life in sea canyons, and, oh yeah, a slight possibility of seasickness).

I did not have an opportunity to use the Offshore Sea Life ID Guide to identify marine mammals on this trip, but I did go whale-watching trip with Sarah and Todd last August, and I can see how the book would have enriched the experience. The species accounts for whales and dolphins are slightly more extensive than those for seabirds, focusing on behavior (fluking and breaching for whales, acrobatics for dolphins and porpoises) and whether they tend to travel alone or in pairs or groups. The photo composites illustrate the many different ways these creatures may be seen from a boat. Tail, fin, blow, and back for whales; fin, back, leaping whole body, and tail splashes for dolphins and porpoises.

We saw two Blue Whales on our trip, quickly identified by the boat’s crew. The Blue Whales were impressive, but what really delighted us were the joyous frolics of the hundred or so dolphins we encountered. That’s when this book would have really come in handy! Did we see Common Bottlenose Dolphins or Common Dolphins? Probably the latter (“often in large, fast-moving, and acrobatic groups, splashing the surface into a white frenzy”). Did we see Short-beaked Common Dolphins or Long-beaked Common Dolphins? Fortunately, I took photographs. Probably Long-beaked. Although, the use of “‘cuter’ facial expression” to identify Short-beaked Common Dolphins does give me pause. How can a dolphin NOT have a cute face?

I found Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: West Coast to be a well-designed, concisely written, and smartly illustrated quick reference guide. It’s perfect for birders like me, birders who have some experience, but who get all queasy inside at the thought of identifying seabirds on their own. Beginners would benefit from this book as well. Maybe even advanced birders, who like the idea of bringing along a handy, relatively inexpensive quick guide instead of a large, specialized, expensive book (like Petrels, Albatrosses, and Storm-Petrels of North America) that might be ruined by salt water.

There are advantages to using a guide that combines all your possible choices on one two-page spread. There is a lot of convenience in an identification guide that covers marine mammals, and even flyingfish, jellyfish, and krill, as well as seabirds, especially when it is written by Steve N.G. Howell and Brian L. Sullivan. Princeton University Press will be publishing a companion volume, Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: East Coast by Howell and Sullivan in October. I’m looking forward to using it.

Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: West Coast

by Steve N. G. Howell & Brian L. Sullivan

in collaboration with Todd McGrath and Tom Johnson

Princeton University Press, June 2015.

56 pages, 300+ color photos (combined on composite plates), 1 map.

ISBN: 0691166137; 9780691166131.

$14.95, paperback (discounts from the usual suspects)

$11.68, Kindle edition

Donna, would you mind sending/sharing/posting your photo of the Buller’s Shearwater? Also, did you leave out of Long Beach or Newport Beach? Thanks.

Hi Tom–We left out of Long Beach. My rule is to not include personal photos in book reviews. Here is a link to the photo that was attached to my eBrid report. It’s heavily cropped: https://flic.kr/p/uVc7Rm

Nice! Extremely rare in the Catalina Channel.

I was quite astounded when I saw the photo! But, the bird was on the eBird checklist, so it didn’t pop up as a rarity. A couple were also spotted off of San Clemente Island that day.