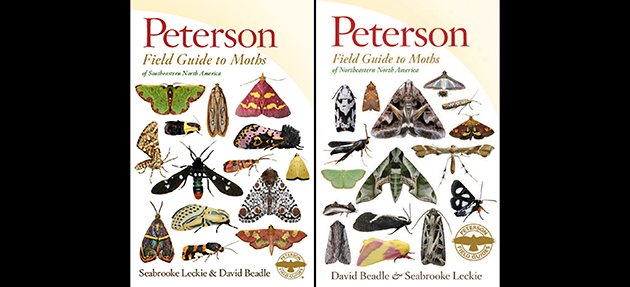

Happy May Day! Here in New York City, May is a magic time for birders as the migration floodgates open. To celebrate spring migration, I usually review an exciting new bird book. But, this year I’m going to be contrary and give you moths! You can blame the nice people at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, who took it upon themselves to send me a review copy of the Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Southeastern North America by Seabrooke Leckie and David Beadle. Looking through this compact yet extensive guide, I realized that I have been amiss in not reviewing the first book of this series, the Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America by David Beadle and Seabrooke Leckie (same authors, order reversed), published in 2012. So, here, for May, is a review of two amazing field guides, reminders that there are strange and wonderful things out there in the natural world other than birds that deserve our attention.

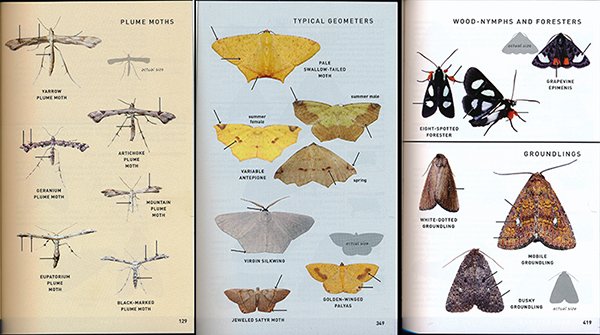

Moth plates from Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Southeastern North America

I’m pretty sure every review of these guides starts with some mention of how moths are the derided but majority member of the order Lepidoptera, and how their gaudier cousins, those fancy butterflies, hog all the spotlight and field guides. But, there have been exceptions. There is the “The Moth,” a storytelling group popularized by The Moth Radio Hour. The group’s name is in honor of the moths attracted to porch lights in evenings gone by, when storytellers would sit and tell tales on these porches. And, there is a fairy named Moth in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and a superhero named The Moth, appropriately from Dark Horse Comics, the poor cousin to the two big comic book companies.

And….that’s about it for positive moth images. Excepting the images of the moths themselves. Flip through the pages of each guide, and you’ll see a crazy diversity of shapes and hues–spheres, triangles, rods, arcs, and airplanes, colored in subtle shadings of gray and brown, deep bronzes, fuzzy whites, veined yellows, elegant greens, even some rosy pinks, all decorated with intricate lines, dots, and patterns that seem impossible to duplicate. Moths are more than bird food.

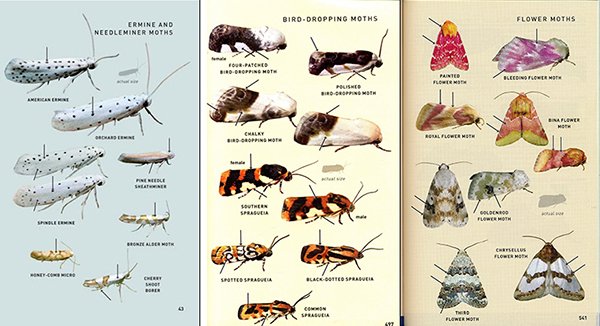

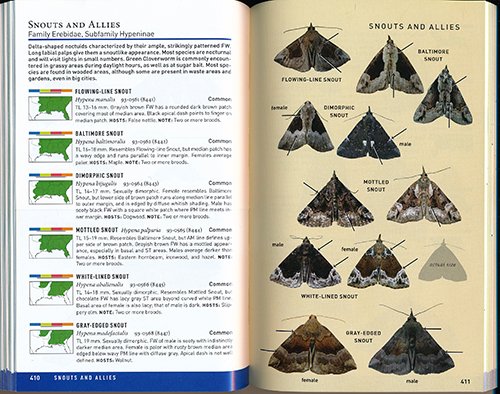

Moth plates from Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America (left plate) and Southeastern North America (two right plates)

There are over 11,000 species of moths in North America. This is the first thing we learn in the Introduction of each guide. Let that sink in. I have a hard enough time with the 1,103 bird species on the ABA Checklist. Leckie and Beadle have selected a smaller number to cover in each guide–1,500 in the Northeastern guide, 1,800 in the Southeastern—the most common or “most eye-catching” moths. The states covered in each guide are shown on the cover page in case you’re not sure if your area is covered. The Northeast goes as north as southern Ontario, Quebec, and North Brunswick, west to the western borders of Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri, and south to the southern borders or Missouri, Kentucky, and Virginia. The Southeastern guide goes a bit more west, to eastern Oklahoma and Texas, so its northern borders lie at the north boundaries of Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

Organization and Content

The guides are organized taxonomically and laid out in the traditional Peterson manner—illustrations on the right, text of the left. Families, or in some cases subfamilies, are tied together with brief descriptions of shared family (or subfamily) characteristics: physical, behavioral, sometimes habitat, nocturnal or diurnal flight, and if the species comes to lights. There is no listing of the families and subfamilies in the Table of Contents, so if you are looking for a specific group, you can browse through the family names printed in white against blue on the bottom of the text pages or consult the index. The Northeastern guide also has a checklist in taxonomic order in the back of the book. The Southeastern guide doesn’t; I imagine this was to save space in a book with 300 additional species. (And, to be fair, many field guides don’t list families or other groupings in their Table of Contents; it’s something my librarian mind doesn’t understand.)

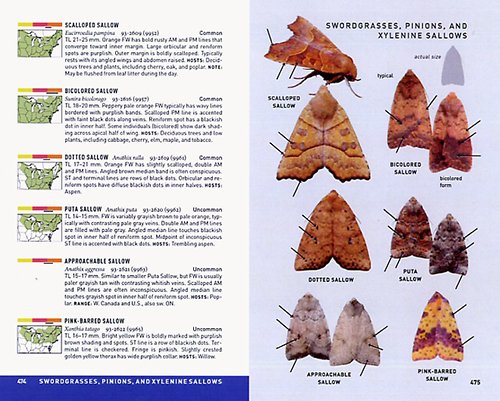

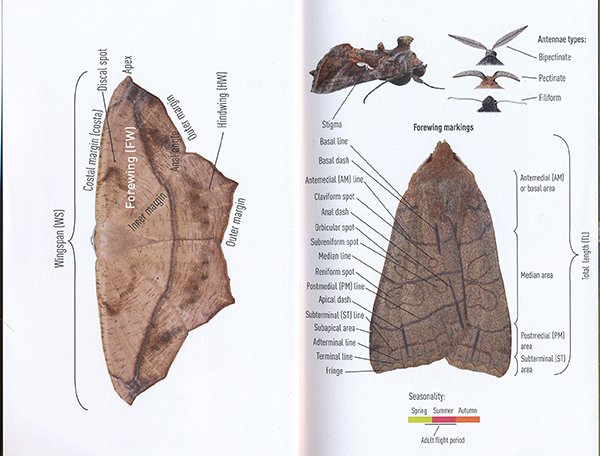

Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Southeastern North America

Text entries for each moth species include common name, scientific name, Hodges and P3 numbers (these identification numbers are explained in the introduction), size (either wingspan or total length), abundance (common, uncommon, local), host plants, and, for some, notes on broods or whether it’s an introduced species. A brief paragraph—three to five lines, generally four—describes what the moth looks like and distinctive features—lines, dots, scallops on the edges–to look for. Each species account has a four-part bar to the left with a line underneath indicating seasonality of flight periods. The text regularly makes use of abbreviations and anatomical terms that make them, at times, cryptic. Here’s an example, from Hagen’s Sphinx, SE guide, p. 260: “Light gray FW is tinged variably mossy green or brown along costa and in ST area. Dark zigzag AM and PM bands are connected by dusky patch in inner median area. Shows pale patches in outer median and apical areas.” These are quickly explained by the anatomy diagrams on the first two pages. I wish they could have been on the inner front cover because I’m sure I will wear out the page edges with my constant thumbing. Then again, I may actually remember that AM band means Antemedial area, the area at the base of the wings.

Most, but not all, species accounts have a range map, and the account given in the introduction of how the range maps were conceived and drawn reflects the ingenuity and dedication of the authors. To make a long story short, we don’t know very much about moths’ geographical ranges; but we do know their host plants and we know that their existence is tied to these plants, and we know that the plants are part of specific ecoregions. And, the North American Environmental Atlas project documents the locations of these ecoregions. So, range maps were constructed based on ecoregions. They are not, as the authors admit, totally perfect, but they do give us some idea where each species is likely to be found, and hopefully future sightings and documentation will lead to more specificity. (It’s not clear why there are no range maps for all species and why the absence is concentrated in the families in the beginning of each guide. Those species without maps have general descriptions of range in the text.)

Photographic Illustrations

Moth photographs are the core of these field guides, and they are impressive, especially considering how many moths needed to be illustrated. The images are sharp and well-colored. They’ve been stripped of their background and carefully arranged on the page against backgrounds of white, peach, light-green, and other pale colors that separate taxonomic groups but don’t distract from the moth focus.

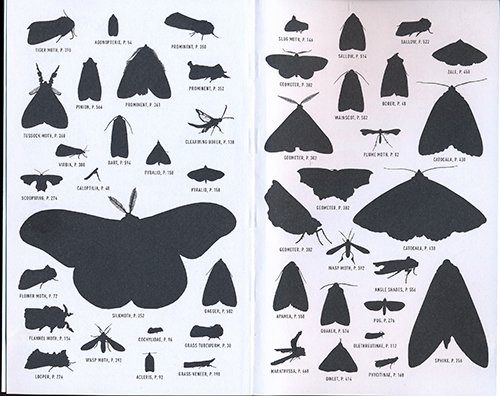

In Peterson field guide style, arrows point to distinguishing field marks described in the text. All images on a page are sized proportionally to each other, or to those moth species in their group when two groups share a page. The sizes are not true to ‘real life,’ so, to give an idea of real life size, one image on each page is shadowed by a silhouette of the true size. In most cases, this means we have to think of the illustrated moths as smaller, much much smaller than they are on the page. But, then there are families like the Royal Silkworm Moths,which are larger, much much larger.

Most species are depicted with one photograph, few with two. Many of the species accounts for the dimorphic Snouts, for example, show both the male and the female. All moths are depicted in the position it is most likely to be seen in the field (or on a moth sheet)–wings spread out or wings folded or in tent-like positions. It can’t be stressed enough how innovative an approach this is. The only previous North American field guide to moths, Charles V. Covell’s Peterson Field Guide to Eastern Moths (Houghton Mifflin, 1984), featured drawings of moths with the wings spread out, a classic scientific illustration style reflecting the way collectors display moths and butterflies. It’s prettier and more decorative, but not helpful for identification.

I assume most of the photographs are by the authors, though their individual contributions are not separated out. David Beadle has a number of bird books to his credit; he is co-author with James Rising of Sparrows of the United States and Canada: The Photographic Guide (2001), and has contributed both illustrations and photographs to many other guides, including the forthcoming Antpittas and Gnateaters by Harold Greeney. Seabrooke Leckie has an educational background in zoology and is a freelance writer and naturalist who has worked on field research contracts in many areas of North America and who, if you look at her Flickr site, has talents for both illustration and photography.

In addition, 43 photographers contributed to the Northeastern guide and 79 photographers contributed photos to the Southeastern guide, all listed in the back with references to each photo. The Southeastern guide has many more contributed photographs, which makes sense since the authors are from Canada. The contributors include Parker Backstrom, Ken Childs, Mark Dreiling, and Carol Wolf (impressively, 870 photos).

Introductory and Back-of-the-Book Material

Surprising, Leckie and Beadle spend little time on the question I’m sure all moth beginners will have, “What is a moth?” It isn’t till page 9 that we find out that if the antenna is clubbed at the tip, it’s a butterfly and that “if it’s threadlike or feathery, it’s a moth.” This is a little simplistic–there are exceptions (aren’t there always?), and there are other ways to distinguish moths from butterflies. The authors, it seems, don’t want to dither around with ifs, ands, and buts. Nor with scientific language. This is a straightforward and easy to read introductory section that focuses on making the subject of moth identification clear to even the most elementary beginner.

So, this section, entitled “How to Use This Book,” focuses on how to see moths (setting up a moth sheet, light trap, sugar bait, in the wild), advice on how to start learning about moths (start with a small group of common moths, or bright moths, build skills over seasons), how to identify moths (size, position, shape, color, pattern), and how to read the species accounts. The sections are fairly similar in both books; there are some minor changes in language, and one section in the Northeastern field guide, about photographing moths, is omitted from the Southeastern field guide.

Both back-of-the-book sections feature a very useful glossary, which supplements the anatomical diagrams in the front. The helpful Resources section includes both print and online resources, plus, in the Southeastern guide, a listing of two public events that started after the publication of the Northeastern guide–the Ohio Mothapalooza festival and National Moth Week.

The indexes in both books thoroughly index scientific and common names. Users should keep in mind that a common species name like ‘Imperial Moth’ is listed under the major subject heading ‘Moth,’ but the family name ‘Bird-dropping moth’ is itself a major subject heading. A little confusing until you start using the book, then it all makes sense. The last two pages of the book are the moth silhouettes, pages that are likely to be the starting points for many of us.

Conclusions

There is a growing consciousness amongst naturalists, amateur and professional, that we know too little about moths. They are pollinators with their own kind of beauty that hold important niches in our ecosystem, and are thus worthy of our observation, study, and identification. The publication of the Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America has contributed immeasurably to the growing naturalist interest in moths. Knowing the names of living things makes them ‘real’ to us, adds value. Which leads to greater support and funding for conservation measures. I can’t imagine the extent of the research, organization, and hard work that Seabrooke Leckie and David Beadle put into this volume, and I find it somewhat shocking that they actually did it again with the Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America. Both authors are self-professed moth hobbyists, but it’s clear that they bring to these guides professional accuracy, thoroughness, obsession with detail, as well as artistic senses of graphic clarity and pictorial organization. If you bird in eastern North America, northeast or southeast, these are volumes you will want in your field guide collection. You may not want to identify moths now, but there is a good chance that you will be looking at these creatures in the near future and wondering if it’s a looper, sallow, or glyph.

Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Southeastern North America (Peterson Field Guides)

by Seabrook Leckie & David Beadle

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April 2012, $29.

paperback, 640 pages, 4.5 x 1.4 x 7.2 inches

ISBN-10: 054425211X; ISBN-13: 978-0544252110

Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America (Peterson Field Guides)

by David Beadle & Seabrooke Leckie

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April 2012, $29.

paperback, 624 pages, 4.5 x 1.3 x 7.2 inches

ISBN-10: 0547238487; ISBN-13: 978-0547238487

[Lower prices available from the usual suspects.]

Leave a Comment