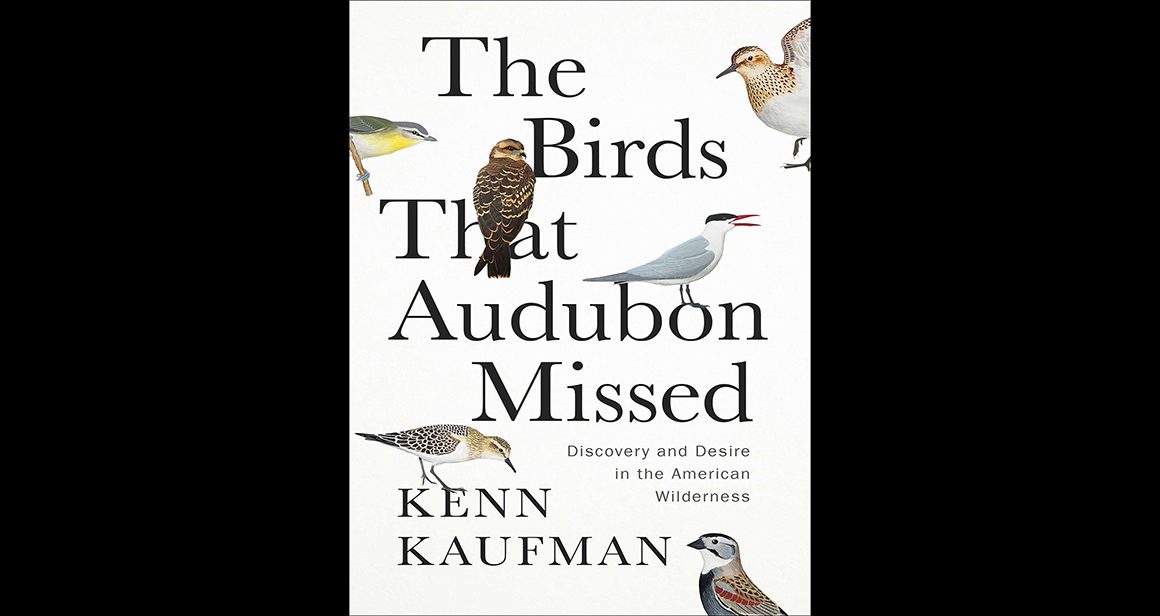

The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness is about birds and taxonomy, history and art, the birding god we have revered and torn down, the ornithological originals we’ve ignored or simply don’t know. It’s also about personal journeys, where knowledge comes from and how it is shared, investigating the past through the lens of history and the lens of informed imagination, learning how to negotiate the grays of our ornithological heritage, and the magic of discovery. I wouldn’t expect anything less from Kenn Kaufman, writer, illustrator, editor, and birder extraordinaire. It’s a decidedly different direction for the author of Kingbird Highway (1997), Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America (2005), and A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration (2019), to cite just three of his books, and one that I thoroughly enjoyed, underlined with energy, and am still thinking about.

In The Birds That Audubon Missed Kaufman looks back to the golden age of ornithology in North America, the late 18th and 19th centuries, when birds were discovered and named and painted and described. There were also many birds, he points out, that our birding fathers (sadly, no ‘mothers’ unless you count the patient Lucy Audubon, and we probably should) did not describe and paint. And some birds they described that did not exist or were really birds already described and named. It’s a fascinating cast of ambitious and brilliant characters: John James Audubon, self-involved with a core of artistic genius, also Alexander Wilson, Charles Lucien Bonaparte, Mark Catesby, George Ord, Spencer Baird, John Townsend, and many others, with guest appearances by Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and a few contemporary figures–Roger Tory Peterson and Victor Emanuel. Their discoveries, writings, art, and lives are woven in and out of chapters focused on bird families (thrushes, shorebirds, warblers), places (Florida, Texas), significant points in North American ornithological history (Wilson versus Audubon in Philadelphia), and the big topics of taxonomy and conservation.

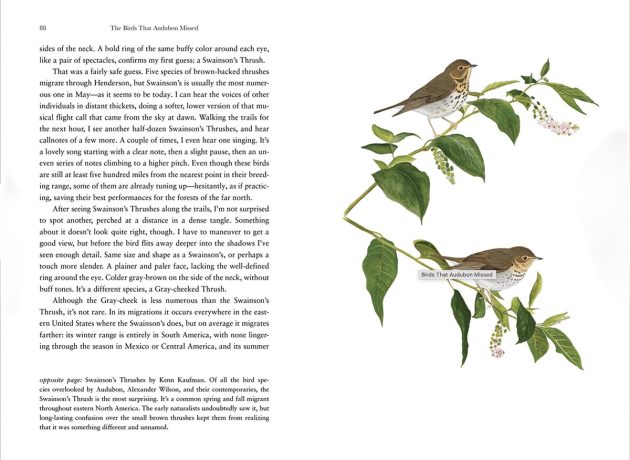

Kaufman says he worked on this book for five years and it shows in the depth of research, scope of topic, and the elegance of his writing. He brings together historical and scientific timelines, taxonomic descriptions, biographical anecdotes, entries from explorers’ journals, recent scholarship (notably Matthew R. Halley’s research on Audubon) and personal reminiscences to bring to life the passions and mundane realities of this age of avian discovery and to investigate exactly why Audubon (and Wilson and other early ornithologists) did not illustrate or describe a number of familiar birds. The list includes Swainson’s and Gray-cheeked Thrushes, Philadelphia Vireo, Caspian Tern, Western and Baird’s Sandpipers, Snail Kite, Carolina Chickadee, King Rail, Thick-billed Longspur, Kirtland’s Warbler, Western and Clark’s Grebes, and several of the Empidonax flycatchers. It’s not always a straight line to the answer.

Clearly, many of these absences are from families still confusing birders today–sandpipers, flycatchers, thrushes, warbles. And, of course, 18th-and 19th-century naturalists did not have our optics and communication technologies. Less obvious, and what Kaufman does such a great job of delineating, is the state of ornithological thought at the time, the lack of knowledge about migration patterns, seasonal plumage changes, geographic variations, and the emphasis on identification by physical features, excluding voice. (Kaufman also makes clear that knowledge about North American birds did not start with Catesby, Wilson, Audubon, etc., that there were diverse peoples here before Europeans started naming birds, who had their own expertise.)

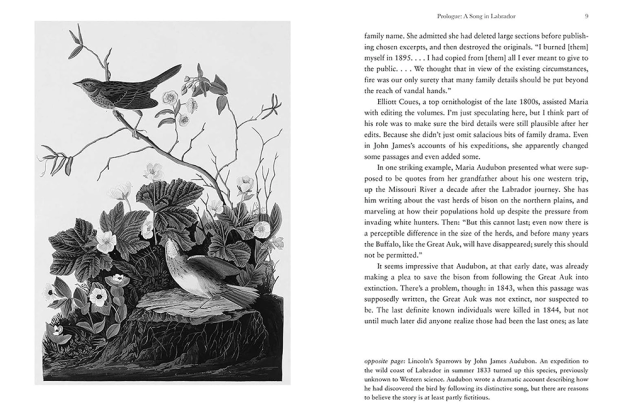

pages 8 & 9, Lincoln’s Sparrow by John James Audubon and text by Kenn Kaufman, © 2024 Kenn Kaufman

The protocol for who got to claim credit for discovering a bird species was an important factor. It’s a protocol still in place today–first person to describe the bird gets the credit and gets to name the bird. In the time of Wilson and Audubon, bird discovery was also an entryway to distinction, money, and what we today call celebrity. This is the root of the rivalry between Alexander Wilson (and his followers) and the larger-than-life John James Audubon, the self-styled “American Woodsman” who had crafted a persona that a reality TV star would envy. Much of this material takes place in “Feuding in Philadelphia,” an aptly named central chapter, but Audubon’s eagerness to find new bird species echoes throughout the book; we see him describe “new” species that already exist, insert himself into adventures experienced by his companions, even fabricate birds (notably, his Bird of Washington). All the early ornithologists made mistakes in species identification; Audubon’s often seemed rooted more in ambition and mythmaking than ignorance and confusion. Kaufman is clear-eyed about the many facets of the man, expressing anger at his history of owning slaves, respect for his artistic genius, and wondering in the last chapters how we can reconcile the good and the evil of Audubon and, indeed, many of our historical leaders.

Other material, particularly sections tracing out the historical taxonomic puzzles, can be a bit challenging. In the chapter “A Thicket of Thrushes,” for example, Kaufman traces the lines of confusion that surrounded the description and naming of Eastern thrushes, starting with Mark Catesby’s write-up of “Little Thrush” in 1731. Successive naturalists described and drew additional Little Thrushes, each somewhat different, combining features of Hermit Thrush, Veery, Gray-cheeked Thrush, and Wood Thrush, and sometimes a characteristic that didn’t apply to any of them. Alexander Wilson wrote descriptions of Wood Thrush, Hermit Thrush, and Little Thrush, stating that his Hermit Thrush was based on previous descriptions of Little Thrush and that his Little Thrush was a new species. Audubon illustrated and wrote about a Tawny Thrush which looked like it could be a Veery or Gray-cheeked Thrush (depending on who you read) but whose description could have applied to any of the thrushes; he painted a Little Tawny Thrush which he later renamed Dwarf Thrush in his description, declaring it a new species. The mind reels. Kaufman patiently goes through every thrush iteration, naming naturalists and books, outlining modern interpretations, allowing us to appreciate just how crazy it was to be a naturalist in the golden age of discovery, the great opportunities for finding treasure (new birds), the huge gaps in observation and information that allowed charismatic naturalists to create birds that didn’t exist.

This isn’t a biography of Audubon nor a straight-forward history of his times, as Kaufman points out in his first chapter. Historically oriented chapters, boldly numbered and titled, are separated by briefer sections called “Channeling the Illustrator.” Here Kaufman presents his progress and thoughts as an artist; he has set himself the task of drawing the birds Audubon missed as Audubon would have painted them (though without shooting them). This very personal project was initially motivated by his review of National Audubon Society’s online gallery of all the color plates from Audubon’s Birds of America, where he first realized Audubon’s significant misses, and then pushed to actual implementation by Covid isolation. If this was a novel, it would be called a narrative framing device, and it works in much the same way here, enabling Kaufman to comment on Audubon’s artistic technique and creativity, to imaginatively approach and value him through his drawings in ways he can’t in the historical context. It also gives us additional information on how Audubon created his images, the tools and processes he used. I really enjoyed these sections.

Kaufman’s artistic endeavors are presented throughout the book, in black-and-white drawings and in the 8-page color insert of 11 of Kaufman’s paintings. (The image of Swainson’s Thrush shown below is presented in black-and-white on page 89 and again in color in the insert. The image I use here is possibly from the Kindle edition or put together by the marketing department, it was downloaded from the book’s Amazon page.) Audubon’s paintings are also presented throughout, illustrating stories such as the creation of his “Bird of Washington” and puzzles such as his “Schinz’s Sandpipers,” thought to be White-rumped Sandpipers but painted without the white rump (so maybe the then unknown Baird’s Sandpiper).

Swainson’s Thrush by Kenn Kaufman, © 2024 Kenn Kaufman

The Birds That Audubon Missed offers a two-page “Further Reading” list of books on ornithological history and biographies of Audubon, Wilson, and several other people of note featured in the book. It does not have a bibliography, which I very much missed. I especially would have liked citations to Matthew Halley’s research, which is cited throughout the book, and to Rick Wright’s blog. (Wright’s work is not cited, but you can’t read this book and not think about his similar investigations of ornithological questions using open-source historical sources. Both he and Halley are thanked with generosity of spirit in the Acknowledgements.) I understand what the problem might have been–Kaufman used many sources (he says in Acknowledgments that he “read thousands of pages of publications from the 1700’s and 1800’s”) and listing them in a formal bibliography was probably out of the pale for a popular nature book published by a mainstream publisher. Fortunately, all older titles can easily be found in the online Biodiversity Heritage Library, as Kaufman points out, and Halley and Wright’s articles are also easily found online. There is also an excellent index, which I found very helpful in writing this review.

Known primarily for his big-year bildungsroman, Kingbird Highway (1997), his field guides on bird, butterfly, insect, and mammal identification (some co-edited with spouse Kimberly Kaufman), and his writings on migration as seen from his beloved home in Ohio, The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness may seem like a dramatic change of direction for Kaufman. I don’t think so at all. North American ornithology and birding has a fascinating history that hasn’t been explored enough, and Kaufman clearly has a curiosity and love for all things birds and birding culture, past and present.

Kaufman makes clear that his motivation for writing this book is personal, to answer intellectual and artistic questions. Yet it is being published at a time when the birding community is grappling with the twin controversies of the Audubon name and the names of birds, and Kaufman writes about these issues in the last few chapters, presenting them in a historical context that should be informative to readers not from the birding community. Perhaps more importantly, Kaufman talks about the possibility for discovery in the present age. The golden age of bird discovery, characterized by individual obsession, guns, and an abundance of birds, ended in the 1880s. “But that wasn’t the end. Changes in definitions, changes in understanding, and changes in methods would keep the age of discovery alive” (p. 347). Subspecies, identification of species by call note, DNA research, introduced species, explosion of species’ boundaries due to introduced apple snails, communication networks that allow for extensive teamwork–these are the elements of discovery today, and all birders can participate.

I highly recommend The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness to all birders and naturalists, those entering the field and those with lengthy life lists. Its unique blend of ornithological taxonomic history and biography, analytic critique and personal memoir, written in an engaging style that entertains, enlightens, and educates. This is a wonderful addition to Kenn Kaufman’s long list of books and his final commitment to personal discovery is inspiring in many ways. I saw an American Flamingo in East Hampton, New York two days ago, several miles from where I used to summer with my daughter, 100 miles where John James and Lucy Audubon spent their last days. Maybe not an official “discovery,” but one that lifted my heart. Maybe I’ll even draw that Flamingo and think of Lucy.

The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness

by Kenn Kaufman

Simon & Schuster, May 2024

400pp. illus.

ISBN-10 1668007592; ISBN-13:978-1668007594

Hardcover $32.50 (discounts from the usual sources); also available in Kindle and other formats.

Donna,

Thank you! for such a thoughtful and comprehensive review of Mr. Kaufmann’s latest book and of birding knowledge. I am about to start reading it in preparation for a book club discussion, and your assessment is providing an overview and guide. Thank you also for links that enhance learning as well as the delight of learning . Drina

Hi Drina–Thank you so much for your appreciation of Kenn’s book and my review. As a librarian this is exactly what I’m aiming for. I hope the book club discussion was lively, educational and fun.