Chemistry is everywhere—at least that is what chemists like me tend to believe. In this new, irregular series, I will look at the intersection of avian life and chemistry – a surprisingly vast topic. The Venn diagram below illustrates the topic of this series without supplying any additional information whatsoever.

In Papua New Guinea, a bird family named Pitohui is called “rubbish birds” by the local people, who do not hunt them while hunting many other birds of a similar size. Why? The birds are toxic and thus cannot be eaten without dedicated preparation. As so often in science, the natives understood this fact long before a scientist, Jack Dumbacher, experienced a burning sensation when licking a scratch on his finger after handling a Hooded Pitohui.

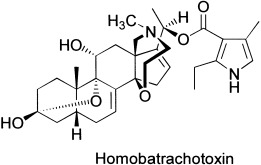

However, Dumbacher then did what any good scientist would have done: he followed up. Specifically, he analyzed feathers of the bird and found that they contained a toxin with a sufficiently off-putting name and frightening-looking formula, homobatrachotoxin.

Subsequent research identified several other toxic bird species apart from pitohuis: Blue-capped Ifrita, European Quail, Spur-winged Goose, North American Ruffed Grouse, Brush Bronzewings, European Hoopoes, and Green Woodhoopoes.

For most of these species, their toxicity comes not from toxins produced by themselves. Instead, they have outsourced toxin production to (mostly) beetles, which they thank by eating them. Only hoopoes and woodhoopoes have toxin-producing bacteria in their preen glands.

This also explains why not all of these species are toxic all the time. European Quails are not toxic during spring migration, but are toxic in autumn, though only on some migration pathways. In their case, the poison comes from eating poisonous plants, which are only available at specific locations. Poisoning from eating such quails even has its own name, Coturnism. Symptoms of this illness are muscle tenderness and muscle cell breakdown, and cases are even reported in ancient texts such as the Bible – in Numbers 11:31-34, the Israelites become ill after having eaten quail in Sinai.

Getting seriously sick from a bird is an exception, though. Most cases of contact with toxic birds produce only mild symptoms, as the birds are not eaten.

There are several hypotheses regarding the function of the toxins. The deterrence of predators (and presumably, Papua New Guinean hunters) is a preferred one. Support for this hypothesis comes from the bright colors of some toxic birds (though they are hardly alone in that respect), acting as a warning sign to predators, and the fact that some other bird species seem to imitate these colors, presumably to also be regarded as toxic.

Another credible hypothesis is that the toxins deter lice, ticks, mites, and fungi on the bird’s skin or feathers – nature’s way of providing the equivalent of a long-lasting mosquito spray. Indeed, research showed that chewing lice prefer non-toxic feathers and die more quickly in their presence.

Other potential functions, such as the protection of offspring or the simple deposition of toxins in the feathers in order to get rid of them, seem less likely. It is even more unlikely that the toxins have no function whatsoever, as the sequestering of the toxins by the birds, without poisoning themselves, requires substantial effort and chemical changes in something called sodium channel Nav1.4.

And unfortunately, at least for the pitohui, their toxicity does not protect them from the vast Indonesian market for pet birds. Apparently, discussions about pitohuis on online forums rarely mention their toxicity, and when mentioned, it is quickly dismissed by the traders.

Finally, one might even speculate that toxic birds could attract other bird species, happy to form mixed-species flocks with them and thus benefit from their toxicity. Somewhat disappointingly, this is not the case.

Photo: Hooded Pitohui, Mark A. Harper, used under Creative Commons license

Sources:

- When poison takes flight: these birds might kill you – if you eat them

- Avian Toxins and Poisoning Mechanisms

- Chemistry and Ecology of Toxic Birds

- Pitohui

- Coturnism

- Poisonous birds: A timely review

- The role of toxic pitohuis in mixed-species flocks of lowland forest in Papua New Guinea

- Evolution of Toxicity in Pitohuis: I. Effects of Homobatrachotoxin on Chewing Lice (Order Phthiraptera)

- Toxic to the touch: The makings of lethal mantles in pitohui birds and poison dart frogs

- Poisonous pitohuis as pets

Future posts in this series:

- Chemistry of Birds (2): Guano

- Chemistry of Birds (3): Poisoned Vultures

- Chemistry of Birds (4): Eggshells

- Chemistry of Birds (5): Smell

- Chemistry of Birds (6): Feather Coloration

… and more after those. Suggestions for topics welcome!

Never knew that poisonous birds even existed… learned something new today. Quoting Confucius: “Education breeds confidence. Confidence breeds hope. Hope breeds peace.” https://www.10000birds.com/ should be mandatory for world leaders…