I’m writing this on a hot midsummer’s day with the doors to my study wide open. There’s not much bird song to be heard now, but what I can hear is the screaming of Common Swifts, flying high over the village where I live. No bird symbolises the hot days of summer in England more than the Swift: the flocks that race like hooligans through our towns and villages on July evenings, screaming ecstatically, capture the very essence of high summer. Once known as devil birds, Swifts have always been creatures of mystery, appearing suddenly in early May and departing equally abruptly in August. Nobody knew where they came from and where they went to. The pioneering English naturalist Gilbert White thought that they hibernated, but it was Edward Jenner (1749-1823), the man who invented vaccination, who was the first to suggest that they migrated.

Jenner marked several Swifts by capturing them at their nests and cutting out their toes; he discovered that his marked bird returned to the same nest sites in subsequent years. However, his most compelling argument for migration was the fact that the birds he examined in May were fat and in excellent condition, which wouldn’t have been the case if they had spent the winter in a state of torpor.

Though Jenner may have deduced that swifts migrated, the mystery of where they disappeared to remained. Africa seemed to be the destination, and this was collaborated by an observation made by Dr David Livingstone, who reported seeing a flock of 4,000 individuals over the plains of Kuruman in the Northern Cape of South Africa. However, Africa has a number of species of similar-looking swifts that are challenging to identify, so Livingstone’s observation may not have been of Apus apus, the common swift, but possibly A.barbatus, the African Black Swift.

I’ve seen black-plumaged swifts many times in East Africa, and I’ve been reasonably confident that the flocks I’ve seen in November were Common Swifts, not the widespread (and also common) African Swift. These swift flocks follow the thunderstorms, appearing like magic almost as soon as the rain has cleared. The rain triggers the emergence of insects, and these are what the birds are after.

During the 20th century some 170,000 Swifts were ringed in Britain, of which more than 3,000 were recovered. A few of these ringed birds were found in Africa, with several around the Tropic of Capricorn in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the Republic of South Africa, so Livingstone may well have been right. Ringing recoveries only tell us where a bird has flown to, not how it got there: the mysteries of the swift’s migration were finally revealed by birds fitted with geolocators.

Geolocators weigh less than a gram, contain a clock and a light sensor, allowing researchers to plot an individual bird’s migration route. We now know that as soon as our birds have left their breeding areas in August, they head south over France and Spain to North Africa. Here they migrate around the western edge of the Sahara before turning inland towards the rainforests of the Congo, continuing east as far as the coast of Malawi where they remain until late January. They then start their return migration, pausing again in the Congo, before making a sea crossing across the Gulf of Guinea. They then make an important refuelling stop in the skies over Liberia, before heading back to Europe and then to Britain. It’s a remarkable journey, made all the more so because they remain in the air for all that time, even sleeping on the wing.

It’s over a century since W.H.Hudson wrote in his book British Birds “it has even been supposed by some naturalists that when not incubating, the swift spends his entire night on the wing”. Now we know that it’s not just a night on the wing, but a whole year, and for young birds it may be considerably more than a year before they land for the first time after fledging. Swifts are perfectly adapted to a life in the air, feeding, drinking even mating when in the air. Their feet are tiny, set in the middle of the body, allowing them to shuffle onto their nest, but not to perch in a conventional way. Aptly, the Swift’s Latin name, apus, means no foot.

Sadly, Swifts are declining in Britain, victims not so much as loss of habitat – their habitat is the sky above us – but loss of breeding sites. There’s no doubt that before man started constructing buildings, swifts were far fewer in numbers than they are today. No other bird is as dependent on us for its nesting sites as the Swift. They will occasionally nest in crevices in cliffs or quarries, and I have seen individuals nesting in old Scots pine trees in the Caledonian pine forests of Scotland, but 99% of the European population nests in buildings. The favoured nest site is on a flat surface under the eaves of a building, or possibly in a hole in a wall.

Until relatively recently house building was an imprecise art, and most houses had a gap between the roof and the wall where Swifts, along with sparrows and bats, could squeeze through. Today our quest for thermal efficiency means that no modern buildings are built in such a way, while many older buildings have had any potentially draughty gaps filled or blocked. The result is a disaster for Swifts, as every year there are fewer and fewer nest sites for them to use.

Fortunately, help is at hand, and there are several organisations and many people who are doing their best to not only make people aware of the birds’ plight, but also giving positive assistance by erecting nest boxes for them. There’s also a move to make it a legal requirement for all new houses built in the UK to incorporate swift boxes. This is a simple move that would make great difference, but it’s one that has been fought by the house builders, reluctant to add even a modest cost to that of building a new property.

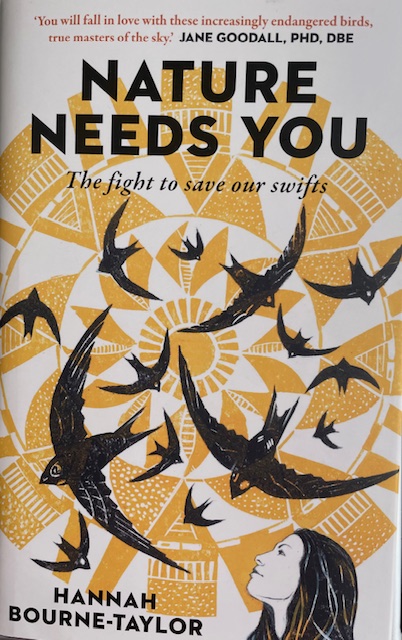

Nobody has fought harder for swifts in Britain than Hannah Bourne-Taylor, the so-called Swift Lady, who has even gone as far as as to walk naked through London, her body covered in painted feathers, to draw attention to the problems Swifts face, and the need for Swift bricks to be incorporated into new buildings. Her book Nature Needs You tells the story of her campaign. It’s a deeply poignant book, in which most politicians, DEFRA (the Department for Food and Rural Affairs) and both Conservative and Labour governments come our badly, as does the seemingly all-powerful Home Builders Federation. Frustratingly, we are still waiting for the legislation to make Swift bricks compulsory.

Hannah writes well, carrying you, the reader, along with the frustrating story of her long battle. The fact that the necessary legislation has still to be made law is a poor reflection on both politicians and house builders. The latter want a voluntary system, but the sad thing is that few will then bother to install a swift brick, which costs a mere £30, so a tiny percentage of the cost of building a new house. The book concludes with an excellent chapter on the fight to save Swifts. It’s noteworthy that the Netherlands mandated Swift bricks in 2024. If the Dutch can do it, why can’t we in Britain?

Nature Needs You, The Fight to Save our Swifts, was published by Elliot & Thompson in May (£16.99). It’s a good read, but it’s bound to make you angry. It certainly made me feel very cross.

Hannah Bourne-Taylor, “the Swift lady”

Excellent read David. Timely as we have had about 30 Swift’s screaming over our tiny village for the last couple of evenings.

Hannah is a true champion.

I love swifts. But “the coast of Malawi”? I always thought of Malawi as a land-locked country?

Sorry – Lake Malawi.

Nature-inclusive building has been a bit of a saga recently in the Netherlands. The very dimwitted minister for Housing Mona Keijser canceled the legislation for swift bricks, bat tiles, etc because “she needed to reduce red tape, not create more”. All builders in the country instantly replied – to their eternal credit – that this was stupid and that the one law replace hundreds of municipal rules. Rather than more red tape, the law was reducing red tape. The construction companies will continue doing the right thing despite the minister’s stupidity. In my opinion, populist dimwittery is the greatest threat we are facing now.

Lake Malawi? They overwinter is such a narrow zone?

(Add the Asian swifts to the picture, all going to Africa, and none to the Subcontinent.)

Common Swift move following the seasonal rains. So, yes, they are at Lake Malawi but also over the Congo. It’s very complex.

Lovely read. Thx for sharing. I have come to love swifts in recent years only. In the region I live now, swifts and swallows appear mostly in the same site and learning to keep them apart is a good exercise in observing these fast moving birds. We have create an ID card free to download here: https://seafile.greensteps.me/f/d0dab51e87074c98b7b3/