“You don’t like shorebirds?” my birding friend asked me in a tone of surprise, shock, and a tiny bit of horror. We had been talking about summer and I imagine that when she exclaimed happily, “Soon it will be time to go to the East Pond for shorebirds!” my face betrayed me. “I love shorebirds,” I replied, “I just don’t always like them.” My feelings about shorebirds came back to me a few days later, as I observed a mixed group of peeps and Dowitchers at Mecox Inlet, eastern Long Island, not far from where Peter Matthiessen once observed the shorebirds of Sagaponack, the stars of the first pages of his classic The Shorebirds of North America (1967). I do not like identifying shorebirds. Unlike many of my friends, I have been slow to master the art of instantly picking out White-rumps, locating the Stilts, and–forget about differentiating between Short-billed and Long-billed Dowitchers! Shorebird identification takes time and is often stressful, there’s heat glare and bugs and drones and dogs and humans. But this does not mean I don’t love shorebirds. I love the complexity of their plumage colors, the energy of their feeding, the sound of new Piping Plover parents calling to their wandering chicks, the mesmerizing sweep of wings and cacophony of sound when they all take off only to land again in the same place.

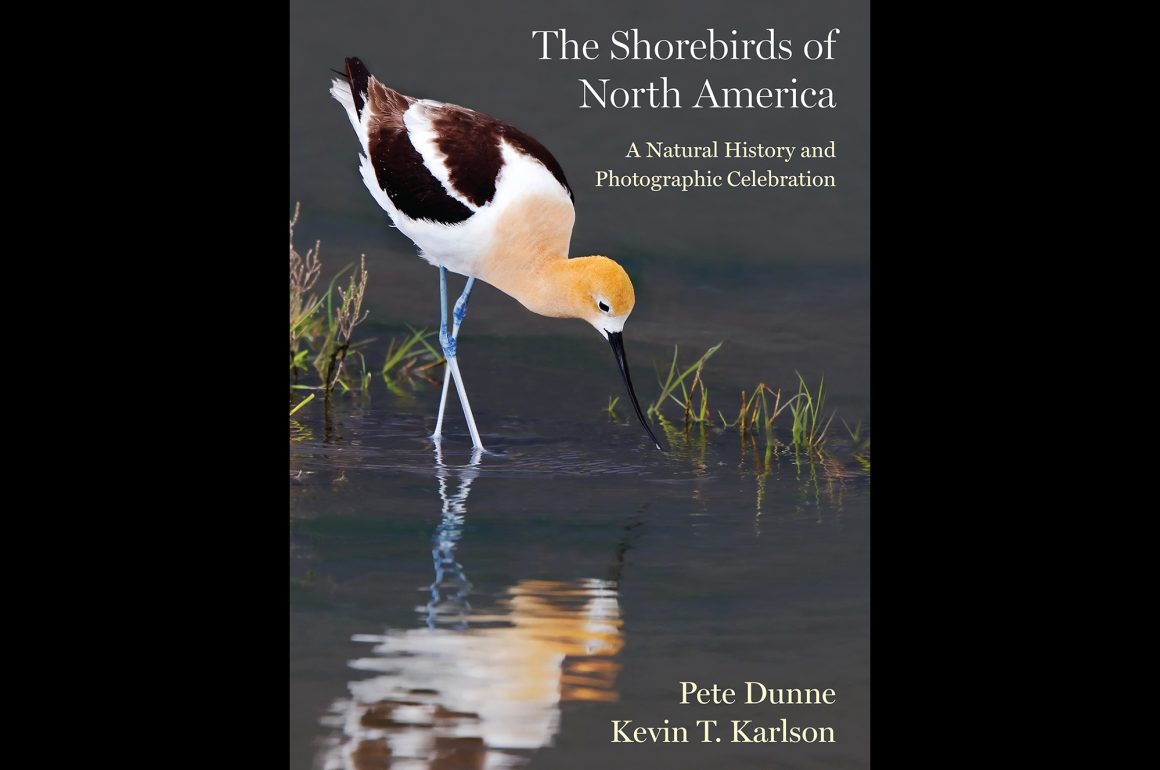

Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson love, like, and respect shorebirds. Their newest collaboration, The Shorebirds of North America: A Natural History and Photographic Celebration, is a glorious combination of expertise, graceful writing, and visual awesomeness. Taking inspiration from Matthiessen’s 1967 book (long out of print), which combined his natural history essays with species accounts by Ralph S. Palmer and watercolor paintings by Robert Verity Clem,* their goal is to present “a textual and visual celebration of the shorebirds of North America that includes a great deal of natural history information, scientific data, and current population numbers and trends for all the shorebirds that breed or regularly occur in North America” (Preface, p. vii). It is pointedly not an identification guide, though there is a lot of identification information in it, and it is not a coffee table book, though every page is illustrated. It’s a book that counterpoints and combines facts and personal experiences, science-based and eloquent writing styles, textual description and visual information, a history of abundance and an uncertain future.

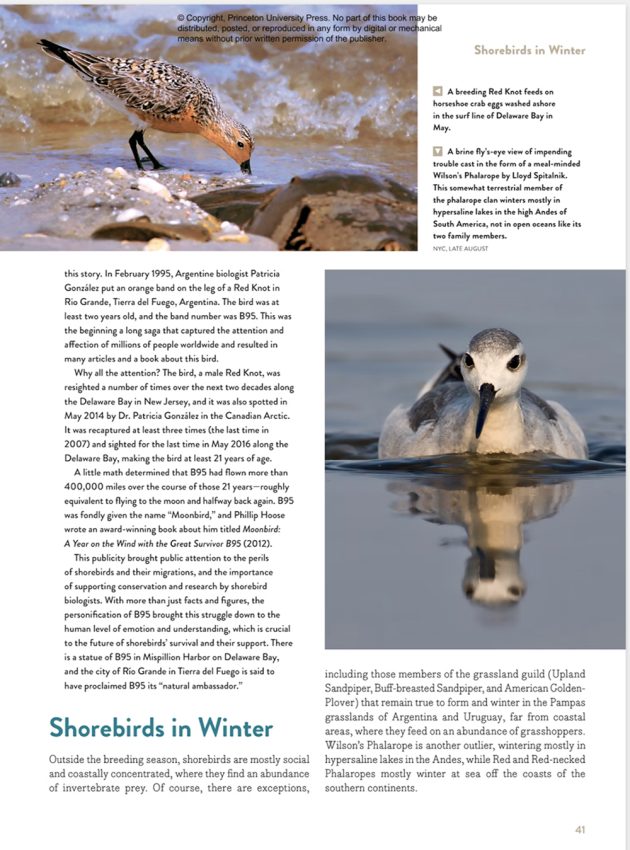

From Part I, “Shorebirds in Winter,” p. 41; © 2024 by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson; lower photo by Lloyd Spitalnik

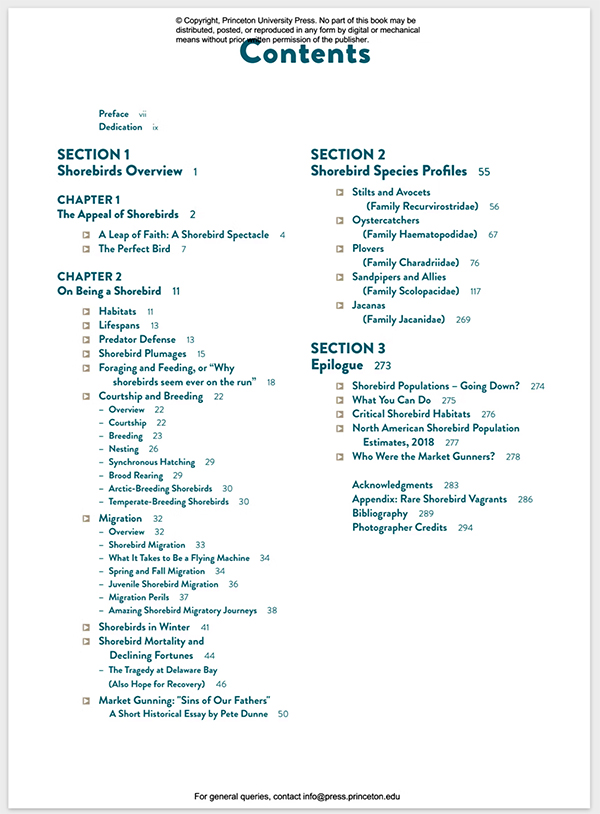

The Shorebirds of North America: A Natural History and Photographic Celebration is divided into three parts: (1) Shorebirds Overview, articles on the natural history of all North American shorebirds, including habitats, lifespans, predator defense, plumages, foraging and feeding, courtship and breeding, migration, shorebirds in winter, mortality and declining fortunes, market gunning; (2) Shorebird Species Profiles of 56 North American shorebird species, organized by family; (3) Epilogue, chapters on shorebird populations, what you can do, critical habitats, population estimates for 2018, and a second essay on market gunners. There are also back-of-the-book sections: acknowledgments, a listing of Rare Shorebird Vagrants, Bibliography, and photographer credits. The book is lavishly illustrated. There isn’t one page that doesn’t feature a captioned photograph, usually two or four, and there are a number of pages that are all photograph and caption, including striking full-page images. Like the book that is its inspiration, the text, images, and species accounts complement and overlap, the essays presenting the broad view of the diverse and similar ways in which shorebirds live and interact with their environment, the species accounts focusing on the specific, expanding on the species’ mentions in Part I, and the photographs giving us visual images of the behaviors and habitats described and their beauty.

One of the purposes of this book is to celebrate shorebirds, and the first chapter of Section 1 does just that, describing “the appeal of shorebirds” and how they might just be “the perfect bird.” If my birding friend needed ammunition to convince me to love shorebirds, here it is: their migration achievements, their diverse breeding strategies, their techniques for evading predators, the way they are anatomically suited for foraging along the shore (or in the prairie), the spectacular energy and beauty of masses of shorebirds feeding during migration stopovers, notably the Red Knots show on Delaware Bay in early spring. The next, much longer chapter, “On Being A Shorebird,” expands on these points, relating in detail the diverse ways 56 species of North American live their lives on their breeding grounds (more than half breed in the Arctic or subarctic areas), before and during migration (there’s lots of preparation involved, fat to store, new feathers to grow), and on their wintering grounds (where we find them reaching “their highest level of artistic expression” (p. 43). Special attention is given to the migration achievements of Bar-tailed and Hudsonian Godwits and Red Knot B95 (known as Moonbird, possibly appearing in one of Karlson’s photographs), and, most importantly, to the plight of the Delaware Bay Red Knots and other shorebirds dependent on Horseshoe Crabs during migration. Dunne and Karlson live and work in Cape May, N.J., near Delaware Bay, and the four-page, fact-filled account reflects personal knowledge of the population crash and research efforts to gather the information needed to fight for governmental curbs on the crab harvest (the focus is more on research than on the large-scale efforts by conservation organizations to put public pressure on government agencies and commissions). Karlson’s photos show both truckloads of harvested crabs and scientists banding Red Knots.

Dunne’s essays on market gunning, which appear in both Section 1 and the Epilogue, provide some fascinating historical context to current struggles to maintain shorebird populations. These days we need to conserve habitat and maintain a balance of food sources. In the 19th- and early 20th-centuries, shorebirds were killed outright for their meat, a trade that only ended with the passage of federal legislation (which still excepts game birds such as woodcock and snipe). I’m familiar with the slaughter of herons, egrets, and other pretty birds for their feathers, but I didn’t know that shorebirds were also targets and that the gunning trade greatly contributed to the demise of the Eskimo Curlew. The gunning trade exploded and shorebird and duck numbers dropped with the use of punt guns, giant guns mounted on boats, and other technological advancements. I did a little research and found plovers and snipe on menus and in cookbooks of the time, though I still haven’t found recipes for Dunlin or Dowitchers. Interestingly, although Dunne’s first essay is factually oriented (it is titled “a short historical essay,”), the second essay, “Who Were the Market Gunners?” reads more like a short story, with Dunne re-imagining dialog and scenes of young men learning the gunning trade from older men. I understand that Dunne is painting a historical portrait of a traditional father-son occupation that died off with the passage of the International Migratory Bird Treaty, but I found it difficult to feel any sympathy for the gunners or their lost skills after reading the first essay.

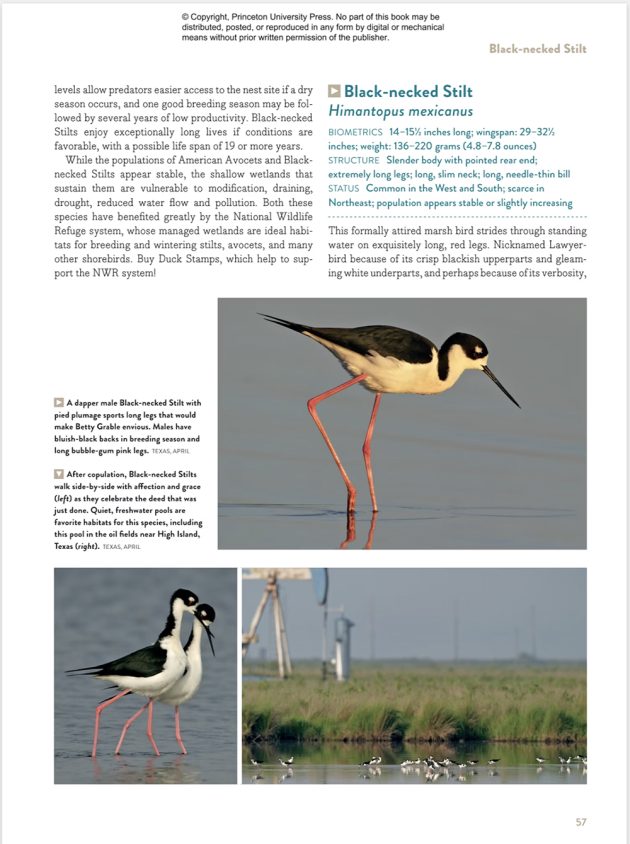

Species Profile, Black-necked Stilt, p. 57; © 2024 by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson

The Species Profiles cover 54 species, the common and not so common shorebirds of oceans, lakes, and puddles, of rocks and jetties, of prairies and grassy fields, of forest floors and dry tundra. There are five families: Stilts & Avocets (Family Recurvirostridae), Oystercatchers (Family Haem), Plovers (Family Charadriidae), Sandpipers and Allies (Family Scolopacidae), and Jacanas (Jacanidae), with Family Scolopacidae representing the bulk of species (as it does worldwide). Most of these birds will be familiar names to birders, even those new to birding–American Oystercatcher, Piping Plover, Sanderling, Semipalmated Sandpiper, American Woodcock–but there are some entries that surprised me, seldom-seen species such as Eurasian Dotterel, Lesser Sand-Plover, and Common Ringed Plover. They apparently meet the criteria for inclusion in that they are regular migrants or annual visitors to specific areas of Alaska.

Each family section begins with an overall introduction to the features and behaviors that are common to all species in the family, their habitats, migratory patterns, and data on how many species there are in the family globally. There are also introductions to a couple of related species within the family sections–Golden-Plovers and Willets. The authors appear to have used the AOS (American Ornithological Society) taxonomy as the basis for names and organization within the family sections, though the Plover section departs from the current order. (This explains the use of the common name “Lesser Sand-Plover” as opposed to the eBird/Clement’s newer name, Siberian Sand-Plover.) A section in the Appendix, “Rare Shorebird Vagrants,” lists 16 additional species that do not show up annually in North America but who have more than ten records; the list notes where the species breed and where their vagrant paths have taken them within North American borders.

The Profiles are engaging reading, much livelier than most identification guides, reflecting the broader scope and goals. Each profile begins with scientific and common names and “biometrics:” measurements and weight, a sentence summarizing “Structure,” and a sentence summarizing “Status” (common or uncommon and where, whether species is endangered). The text describes the species’ appearance, including plumages and molts, habitats, migration patterns, feeding behavior, courtship and breeding behaviors, nest and egg information, subspecies, and population data. There are also unique information bits thrown into the mix–how the bird or the bird’s nests were first discovered, dazzling migratory flight achievements, quotes from poetry, sometimes a personal experience from one of the authors. The lengths of the profiles, including text and photos, vary from less than one page for Eurasian Dotterel to over five pages for Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Karlson’s admittedly favorite shorebird. Most are three to four pages long.

There is a freedom in the writing that we don’t often see in formal identification or field guides. So, the profile of Bar-tailed Godwit starts off with the spectacular nonstop flight of Godwit 234864 from Alaska to NE Tasmanaia, 8,435 miles in 11 days, which leads to Bar-tailed Godwit’s biological preparation for migration and then what we know about the migration paths taken by geographically separate subspecies, and then defensive strategies to protect territory on breeding grounds. Long-billed Dowitcher begins with its taxonomic history, how it was described as a separate species in 1823 by Thomas Say but not accepted as one till 1957. Piping Plover (my favorite shorebird) begins with its designation as Endangered or Threatened, depending on the geographic area and a delineation of the three separate Piping Plover populations in North America. Each shorebird is special, for different reasons.

The photographs in both sections, freed of the technical requirements of formal identification guides, show many of the behaviors described in the text as well as dramatic plumage variations. I was particularly fascinating by the many photos of shorebirds on Arctic breeding grounds, images of them in bright breeding plumages and engaged in behaviors I don’t see when they stop off in Jamaica Bay or Mecox Inlet. They are by Karlson, from his years as a research biologist in Alaska, and Ted Swem, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who lives in Fairbanks, and it is noted that many of these photos have never been published before. In addition to these two, photographers who contributed images to the book as a whole include Arthur Morris (whose photograph of two American Avocets copulating looks even better and brighter than when it appeared in The Shorebird Guide), Brian Sullivan, Lloyd Spitalnik, Mike Danzenbaker, Jamie Cunningham, David Speiser, Julian Hough, Audrey Whitlock, Linda Dunne, Scott Elowitz, Brian Guzzetti, Peggy Wang, Anita North (the stunning photo of a displaying male Ruff opposite the title page), and a drawing by Sophie Webb.

© 2024 by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson

I have one problem with The Shorebirds of North America, and as is usually the case, it concerns usability: there is no index and the table of contents does not list the individual species profiled in Section 2. This means the only way to find a species profile of a specific bird is to guess where it is located within the family section chapters, which are listed (see above). Pretty simple for Stilts and Avocets, Oystercatchers, and Jacanas, a bit more difficult for Plovers, very difficult for Sandpipers and Allies unless you are very familiar with AOS taxonomy and the order in which they list sandpipers. The absence of a listing in the table of contents is puzzling since the chapters and subchapters in Section 1 are listed in detail. It’s also puzzling because the design of the book is very much oriented towards helping the reader locate topics and species profiles through the use of colored banners, large, colored fonts, arrow icons, and chapter headings on the top of every page. So, this is an easy book to browse through, but a difficult book to use for direct reference.

This is not Dunne and Karlson’s first partnership. They have collaborated on four books in the past eight years (this being the fourth, and the third title on a bird family), and I was curious who wrote what. I always like to know how the “sausage” is made. Answering my question via FB Messenger, Karlson wrote, “Pete wrote much of Section 1, but I wrote the Migration and Breeding chapters as I worked in the Alaskan Arctic as a shorebird biologist from 1992-95, and also wrote about 40 percent of the species info at the back of The Shorebird Guide….. I researched much of the natural history and scientific data for the Species Profiles, including current population numbers and its placement in each account, Pete also added some great tidbits about historical and ornithological background for shorebirds. In conclusion, the book was a true collaboration between Pete and myself, with my stronger ID skills and research background providing a solid backbone for the book. Pete’s two essays about the Market Gunners adds a bit more historical perspective about the challenges that this amazing bird family has faced.” (Thank you, Kevin for your prompt response!)

Authors Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson are so well-known in North American birding circles that I wonder if it makes sense to even write a biographical paragraph. But I like doing this, learning about authors. Dunne was director of the Cape May Bird Observatory and vice-president of the New Jersey Audubon Society for many years, till 2014. He has counted hawks, led tours, taught workshops (I attended one by him on how to choose a scope back in around 2006), founded the World Series of Birding, and has written many magazine columns, articles, and books. Notable titles include The Feather Quest: A North American Birder’s Year (1999), Hawks in Flight: A Guide to Identification of Migrant Raptors (with David Sibley & Clay Sutton, 1988; 2nd edition, 2012), Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place (2010), Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion (2006), and The Art of Pishing, (2006). As I noted above, Dunne and Karlson co-authored three books before this one: Birds Of Prey: Hawks, Eagles, Falcons, and Vultures of North America, (2017), Gulls Simplified: A Comparative Approach to Identification (2018), and Bird Families of North America 2021).

Kevin Karlson is a noted nature photographer, writer, tour leader, speaker, and workshop educator. In addition to the books produced with Dunne, he is co-author with Michael O’Brien and Richard Crossley of the groundbreaking The Shorebird Guide (2006), co-author with environmental educator and wife Dale Rosselet of the also groundbreaking Peterson Reference Guide to Birding by Impression, and the writer, photographer and editor of many other books, columns, identification booklets, DVDs, and even an app (on shorebirds!). Both Pete Dunne and Kevin Karlson have encountered serious health problems in recent years. I love the fact that they have continued working, creating books like The Shorebirds of North America, being inspirational in a very low key way, and I look forward to their next book.

The Shorebirds of North America: A Natural History and Photographic Celebration by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson is a special book. I first got a glimpse of it back in August 2023, when Kevin did a presentation at the Jamaica Bay Shorebird Festival. I was enamored with the photographs of American Avocets and peeps, some maybe the same peeps I had seen earlier in the East Pond. The book in hand is so much more than what I expected. I knew I was going to see stunning images, I didn’t expect so much natural history and identification information. No, it’s not an identification book, it is not a substitute for The Shorebird Guide by Michael O’Brien, Richard Crossley, & Kevin T. Karlson (2006) or earlier guides like Shorebirds of North America: The Photographic Guide by Dennis Paulson (2005), but I found a lot in the Species Profiles that I think will be helpful and may even help me like shorebirds a little bit more. This is a large book, but smaller than I expected, 8.25 x 11.5 inches. The 1967 Matthiessen The Shorebirds of North America dwarfs it, but only in size. Because while the 1967 book introduced many people to the wonders of shorebirds, this 2024 version updates readers and increases their wonder exponentially with 50 years of research, 225 photographic images, a well-designed format, and the combined, counterpointed expertise of two experienced birders/writers/lover of shorebirds. I may go to Sagaponack Pond tomorrow and think of Matthiessen, but when I get home, I’ll read about the birds I’ve seen in Dunne and Karlson.

* The Shorebirds of North America, 1967, has an interesting history. It was edited and “sponsored” by Gardner D. Stout, a NYC aristocrat who served as president of the American Museum of Natural History and chairman of the executive committee of the National Audubon Society. It was apparently his idea to put together the essays by Peter Matthiessen with paintings by Robert Verity Clem and species accounts by Ralph S. Palmer, an ornithologist who wrote and edited the five-volume Handbook of North American Birds series. Matthiessen’s essays also appeared in two issues of The New Yorker in 1967 in slightly different form as “The Wind Birds,” but the book notes the text was written “especially for this book.” Reviewing the book for The Auk, ornithologist Joseph R. Jehl, Jr. had high praise for the artwork and species accounts, but found Matthiessen’s text to be “uncritical and speculative….clearly Matthiessen has spent time observing shorebirds, but it is not always evident whether the observations he presents are derived from personal experience or from the literature.” This was probably not the opinion of the reading public, who always devoured Mathiessen’s books on nature and the wild, and the essays were re-published, updated and expanded, in a later book, The Wind Masters (1973), with black-and-white drawings by Robert Gillmor and without species accounts.

The Shorebirds of North America: A Natural History and Photographic Celebration

by Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson

Princeton University Press, June 2024; UK August 2024

Hardcover; 8.25 x 11.5 in.; 3.1 pounds; 304 pages; 225 color photographs

ISBN-10 ?0691220956; ISBN-13 ? :978-0691220956

$35.00/£30.00 (discounts from the usual sources plus from publisher for ebook)

Very thorough review, Donna, fantastic. I may well be on the opposite side of the spectrum: I have very few books on waders (the term shorebird has not sunk in yet, thick skull) and I love identifying them! However, Santa Claus: please consider me for this book too – I have been quite good so far this year…

Thank you for the splendid and thouough review. You are an artist.

I’ll go shorebirding with you any time.

Pete

Thank you, Peter! I was thinking of how “waders” is widely used in countries outside of North America as I was writing the review, it’s an interesting linguistic difference.

Pete Dunne–I am so happy you read the review! I appreciate your comment immensely and hopefully we will meet up on the shores of New Jersey or Delaware some day.