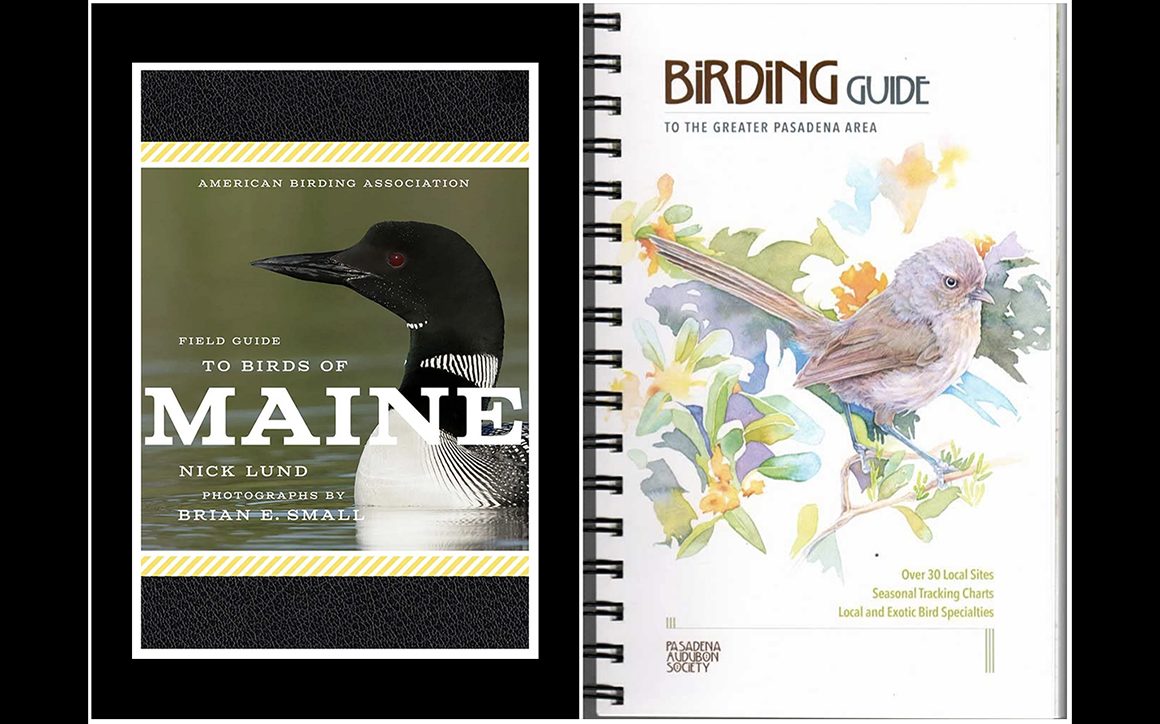

At the end of 2022, let us celebrate the local field guide, a sub-genre that many of us feared would die, the victim of technology, development, and globalization, but which still shines bright, fewer in number but brilliant in quality, thanks to birders and birding organizations that believe in knowing your patch and your state. American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Maine by Nick Lund, with photographs by Brian E. Small and others and Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed., edited by the Pasadena Audubon Society, with illustrations by Catherine Hamilton and photographs by many, are two very different books. They do share important features: authorship by local birders with unique, specific expertise; publication or sponsorship by nonprofit birding organizations; love of local habitats and concern for their conservation; education of new and experienced birders.

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Maine

Nick Lund pretty much says it all when he writes, “Maine left Massachusetts in 1820 to become its own state and took the best of New England with it” (p. xiii). There is no place that compares to Maine with its rocky shorelines, freezing waters populated by wintering alcids, offshore islands filled with nesting Atlantic Puffins, mixed and boreal forests (the most forested state in the U.S., we learn) that are home to coveted boreal species, breeding wood-warblers, and two species of Grouse. And of course, two raptors that are a part of North American birding history: the Great Black Hawk of Portland and the Steller’s Sea-eagle of Boothbay Harbor and other local areas. (A statue now memorializes the Great Black Hawk at its favorite place, Deering Oaks Park, but the Steller’s Sea-Eagle is alive and roaming and has intermittently been spotted in Canada, it may return to Maine soon.) Audubon’s Hog Island Audubon Camp attracts birders of all skills levels every summer and Acadia National Park, Monhegan Island, Machias Seal Island, and Scarborough Marsh are nationally known birding hotspots.

There are 461 species on the Maine checklist. This field guide covers 265 species, the ones most likely to be seen–residential and migratory, almost all nesting birds, many wintering birds. There are charismatic birds like Barrow’s Goldeneye, Evening Grosbeak, Red and White-winged Crossbills; mysterious seabirds like Leach’s Storm-Petrel; ‘little brown jobs’ like Winter Wren and Nelson’s Sparrow; a treasury of warbler species, 27 in all, many state breeders. The book roughly follows American Ornithological Society taxonomic order; a version date or number isn’t given, but it’s probably the 2020 version, before the Big Reshuffle of New World Warblers. So, expect to find warblers before sparrows if you are browsing. Some birds are put next to each other to aid in the identification process, for example, falcons follow hawks. Efforts have clearly been made to update all scientific names. (There is one error or typo, Phalacrocorax auritus (Double-crested Cormorant) should now be Nannopterum auritum, but is the mixed Nannopterum auritus in the Species Account.)

Nick Lund is the perfect person to write this guide. Currently the Advocacy and Outreach Manager at Maine Audubon, he grew up in Maine and has a work history in conservation and public policy including seven years at the National Parks Conservation Association and volunteer work in communications for the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia. He brings to the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Maine a lively prose style born of years of blog writing (initially bird DC and then for many years, still continuing, as The Birdist) and his “Birdist’s Rules of Birding” series for National Audubon.

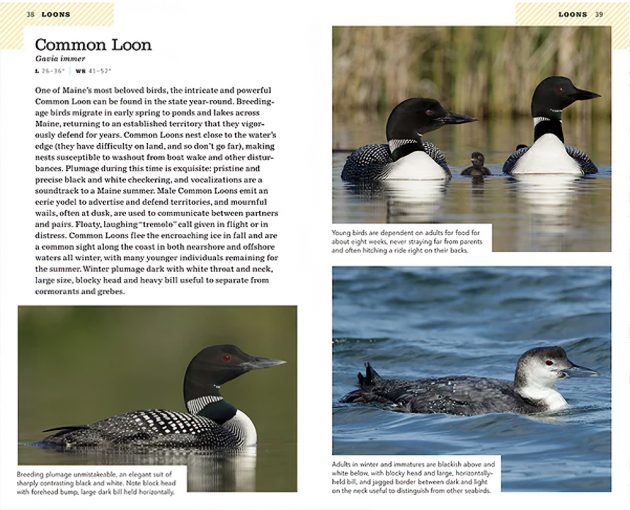

I’ve always wondered, how do you write a species account? How do you craft a description of a common bird like American Robin that’s unique, especially when you’re writing the 19th book of a series? Lund resolves the problem by being specific; every species account is based on the bird’s relationship to Maine–where it can be found, when it shows up and leaves, if it is a state breeder, how it sounds (or does not sound) when in Maine, and, importantly, conservation status in the state. He keeps his irreverent side in check, and though I missed it, as someone who has followed his writing over the years I’m impressed with his discipline. (You can get a flavor for Lund’s cheerful take on birds and life from his regular appearances on the ABA Birding Podcast, including a session on this book and The Joys of Birding Maine.)

In the tradition of the American Birding Association (ABA) Field Guide series, each species is allocated one page with 26 exceptions; these lucky species get two pages. Since many of these exceptions are common birds (Wood Duck, Red-tailed Hawk, Great-horned Owl), I assume Lund saw the additional space as opportunities to teach people how to absolutely positively identify these birds, adding more text and featuring images of the species in flight or in gender-specific, nonbreeding or juvenile plumage. Each Species Account includes: common and scientific name; measurements (length and wingspan); text that summarizes the species’ geographic distribution in Maine, seasonality (resident or migrant, what time of year it is most apt to be seen); habitat; major behavioral traits that aid in finding the bird and identification; major plumage characteristics; calls and songs. Photographic images are large and annotated with specific notes on plumage and behavioral identification features. Brian Small’s excellent close-up photographs are supplemented with images by several other photographers, including Michael Danzenbaker and Garth McElroy.

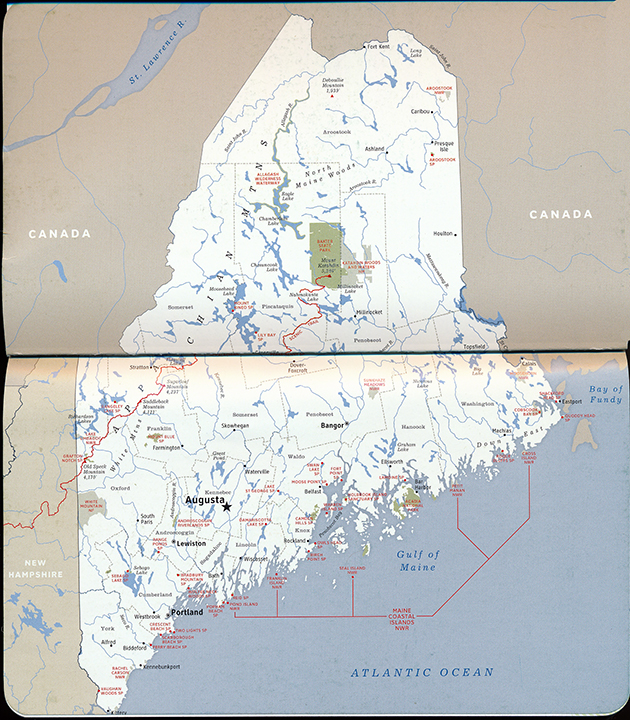

The Guide is organized in the ABA State Field Guide format –map of the state on the inner front cover, ABA Code of Ethics, Introduction, “A Year in Maine Birding” (what to expect every month in terms of migration and where to go), explanation of how the guide is organized and how to use it, “Parts of a Bird,” Resources (including a list of Maine Audubon chapters and their websites). The back of the book consists of Acknowledgements, image credits, Maine Bird Records Committee Checklist of Maine Birds (updated to June 2021), bios of authors, Species Index and Quick Index. I found the latter, printed on one page and easily accessed on the inside back cover, particularly useful. Additional helpful design features include the names of family groups against a yellow-and-white striped background on every page corner and having every bird image facing right (except for that Common Loon chick!), this convention helps the eye compare photos and browse without unnecessary distraction.

Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed.

Once upon a time there were many local birding guides, ranging from thin stapled pamphlets with black-and-white drawings to full-color, professional-level publications. They were written (mostly) by people who knew their patch and published by local bird clubs or small, alternative publishers and the only way to buy them was to write away to a bird club or unearth one in a nature preserve shop. The standard bearer of the regional birding guide was the Lane Birder’s Guide series, eight pamphlet-type books on where to find birds, written by James A. Lane. The Lane Guides told you exactly where to go –what roads to take, what landmarks to turn at–and were filled with local maps. In the back were simple bar graphs showing species seasonality. I have friends who talk nostalgically of birding trips with the Lane’s Guides to Southeast Arizona, or Southern California (there were eight guides in all, some co-written or updated by other birders, notably Henry Holt). The Lane guides were taken over by the American Birding Association in 1990, updated, greatly expanded, and published as the “ABA/Lane Birdfinding Guide series.” (Some titles are still available; A Birder’s Guide to Southeastern Arizona, for example, was updated as recently as 2018.)

Sadly, the number of local and regional birding guides has trickled down to almost nothing. (There are some excellent web guides, like the New York City Audubon “Birding in NYC” guide, but these are not books. I want books!) “Why spend money on a guide on where to find birds when eBird and text alerts will tell me where the birds are?” birders tell me. Well, eBird is great. Text alerts, if you’re lucky enough to know about them, are great (though most don’t allow for information beyond rare bird sightings). This is what eBird and text alerts don’t give us: overviews of the ecology of an area, in-depth descriptions of different habitats in parks and preserves and where you are likely to find specific species, local migration trends, hotspot logistics–parking, bathrooms, hours, websites, accessibility, driving and public transportation directions. I’ve missed this information, especially when I travel to Los Angeles to visit my daughter and her family. So many parks, canyons, mountain trails; so little time.

This is why I was ecstatic when I saw the announcement for Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed. (I didn’t know there was a first edition! It was published in 2005, and I guess was a great success because I can’t find a trace of it online.) The guide, as the title indicates, covers much more than the city of Pasadena. It reaches out to include Glendale and La Cañada Flintridge to the east, the San Gabriel River and Rio Hondo basins in the south, Santa Fe Dam Recreation Area and San Dimas to the west, and, most delightfully, the canyons, divides, day-use areas, visitor centers, roads and flats of the San Gabriel Mountains to the north and northwest. If you are visiting Los Angeles County (the birdiest county in the United States, they tell me), and want to bird this area knowledgeably and efficiently, this guide is invaluable. This is the Los Angeles area where you are most likely to find Wrentit, California Quail, high elevation species like Mountain Quail (sob, my Nemesis Bird), Pygmy Nuthatch and White-headed Woodpecker, plus the famous Pasadena parakeets and parrots and a mixed bag of exotics, some of whom have obtained ABA Checklist status, like Black-whiskered Bulbul, and some that are striking, like Pin-tailed Whydah. It’s also an exciting and incredibly beautiful place to bird, period.

San Gabriel Mountains, @2022, Donna L. Schulman. This photo is not in the book, I wanted to show the beauty of the San Gabriels.

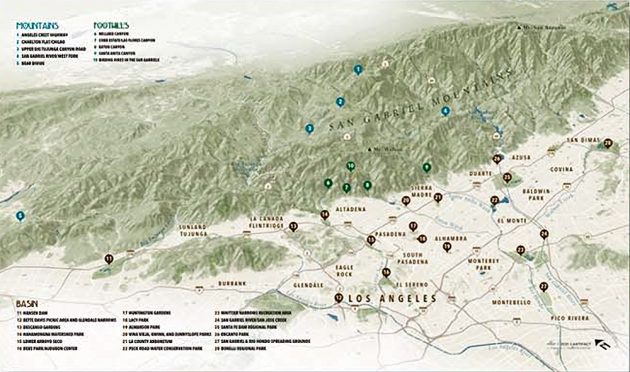

Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed. is organized into three main geographic sections–Mountains, Foothills, Basin. We start at the top, in the wilderness, and then head down, closer and closer to civilization. A total of 27 birding hotspots are profiled, five in the Mountain section, five in the Foothill section, 17 in the Basin section, each hotspot numbered. Additional hotspots are summarized in an Appendix chapter, “Other Sites to Visit.” Each hotspot profile is authored by a birder, a Pasadena Audubon member, who knows the area. This is the best thing about the guide: birders sharing their expertise, earned from years of patch birding, with the rest of us.

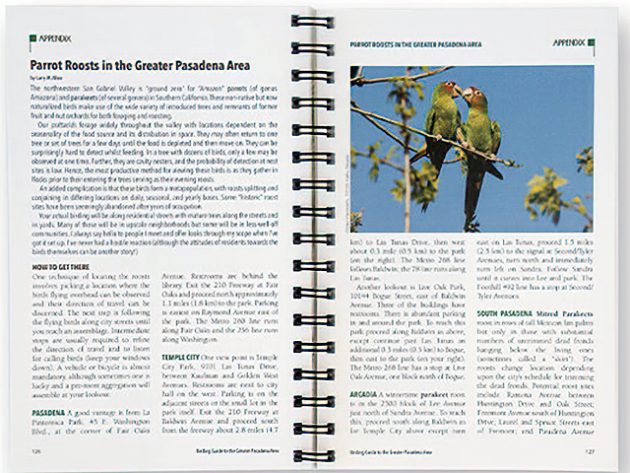

©22 Pasadena Audubon, “Parrot Roosts in the Greater Pasadena Area”

The profiles start with an overall summary of the area–location, agency administrator is there is one, types of habitat, notable water bodies and recreation facilities. There is an icon indicating the total number of birds seen at the site according to eBird as of March 2022. “In Birding the Area” the author takes us ‘birding’ through the park or canyon or road, telling us which habitat areas are best for which birds in this or that season, pinpointing the “birdiest” spots, suggesting when we should drive and when we should walk, all the while listing possible birds in bold print. These routes can get a little confusing in the larger, more complex areas, and thankfully there are maps to guide us, indicating trails, parking areas, best birding spots. The chapters on the roads of the San Gabriels–Angeles Crest Highway and Upper Big Tujunga Canyon Road–will be particularly helpful to birders new to these areas. (And not so new, I’m looking forward to using them. I love the San Gabriels but I also find them very intimidating.) The hotspot chapters close with “How To Get There” by car, public transportation, and bicycle, and “Amenities/Fees”–hours, bathrooms, picnic tables, required passes, fees. All the important stuff they don’t put in eBird.

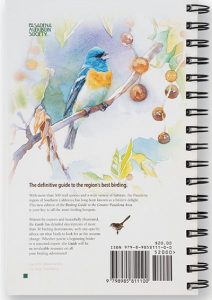

Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area is profusely, almost decadently illustrated with bright, sharp photographs contributed by a large group of Pasadena Audubon members. I would have liked a few more photos of places and habitats, but I understand that birds are the draw here, for contributors and users. And there is original artwork too, by Catherine Hamilton, birder, tour leader, journaling workshop instructor, board game artist, professional bird artist, and Pasadena Audubon member. Her colorful paintings of iconic Pasadena birds in their habitats–Wrentit on the front cover; Lazuli Bunting on the back; Acorn Woodpeckers on the inside front cover; Mountain Quail, Rufous-crowned Sparrow, Cactus Wren, and Mitred and Red-masked Parakeets eating berries on the inside, introducing sections–are pure expressions of avian joy. They also make this a unique birding guide, one I’d buy even if I didn’t regularly visit Pasadena. (back cover: © 2022 Pasadena Audubon, illus. © Catherine Hamilton)

Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area is profusely, almost decadently illustrated with bright, sharp photographs contributed by a large group of Pasadena Audubon members. I would have liked a few more photos of places and habitats, but I understand that birds are the draw here, for contributors and users. And there is original artwork too, by Catherine Hamilton, birder, tour leader, journaling workshop instructor, board game artist, professional bird artist, and Pasadena Audubon member. Her colorful paintings of iconic Pasadena birds in their habitats–Wrentit on the front cover; Lazuli Bunting on the back; Acorn Woodpeckers on the inside front cover; Mountain Quail, Rufous-crowned Sparrow, Cactus Wren, and Mitred and Red-masked Parakeets eating berries on the inside, introducing sections–are pure expressions of avian joy. They also make this a unique birding guide, one I’d buy even if I didn’t regularly visit Pasadena. (back cover: © 2022 Pasadena Audubon, illus. © Catherine Hamilton)

The book is framed by introductory and appendix material, quite a lot of it. There is a foldout color relief map in the front of the book, showing all the profiled hotspots by number (and those numbers labeled above and below, saving us the trouble of flipping pages). There is the formal Introduction, with an “Acknowledgement of Indigenous Peoples’ Lands,” the ABA Code of Ethics, and chapters on “Geography, Habitats, and Climate” (including fire ecology, a very important subject to know about when birding this area), Pasadena Audubon’s conservation work, and a Preface about the guide itself. Its purpose, chief editor Mickey Long tells us, “is to provide useful information for birders of all skill and experience levels” (p. 7).

The Appendix offers a wealth of additional material: chapters on parrot roosts in Pasadena and owls in the San Gabriels; a personal essay encouraging us to bird by bicycle; a lengthy chapter on “Pasadena-area Bird Specialties and Where to Find Them;” the previously cited “Other Sites to Visit;” a seasonality chart showing what birds to expect in what months and in which geographic areas; another chart on “Birding Site Accessibility;” “Resources for Birders;” and a surprisingly good index, much better than the indexes I see in professionally published books.

The goodies don’t stop with the Appendix. There are brief essays and tidbits of information scattered throughout the main sections–an essay about the Wrentit, two essays on exotic species in the area, boxes suggestions for gardening for birds, small ways in which we can promote conservation. It can get a bit crowded on some of these pages! Thankfully the font is large and bi-colored and spaces between paragraphs are large, so even the most info-nugget loaded page is readable.

Conclusion

These are two guides with a little and a lot in common. The American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Maine is for beginning birders who live in Maine and for all birders who intend to visit the state. Its Maine-oriented information written by a talented communicator, is the perfect supplement to a Sibley’s, Nat Geo, or Peterson’s. Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed. is a smart model of what a modern-day local birding guide can be. It was obviously a community project and I’m so impressed at the large number of contributors and the resulting professional product. I hope it inspires other local birding organizations to do the same, update their older guides, maybe collaborate on creating a new one. The future of bird book publishing might just be in our local patches.

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Maine (ABA Field Guide series)

by Nick Lund, with photographs by Brian E. Small and others

450 photographs, 344p. (not the 368p. indicated on Amazon), 4.5 x 0.8 x 7.5 inches

ISBN-10: 1935622749; ISBN-13: 978-1935622741

Scott & Nix, Inc., 2022, $25.95

Birding Guide to the Greater Pasadena Area, 2nd ed.

edited by the Pasadena Audubon Society, chief editor: Mickey Long, content editors: Darren Dowell & Mickey Long; illustrations by Catherine Hamilton, photographs by local contributors.

spiral bound, 180p. (incl. cover), foldout map

Pasadena Audubon Society, 2022, $20.

Available from Pasadena Audubon Society, Buteo Books, Theodore Payne Foundation Store, & local nature stores listed on the Pasadena Audubon website.

Leave a Comment