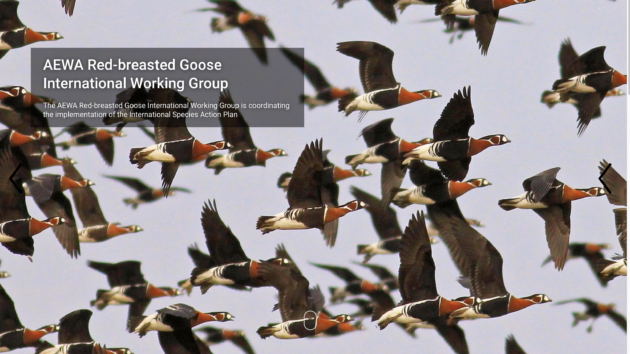

As a general rule, geese are birds of subtle, even dull, plumage. All the so-called grey geese – Greylag, Bean, White-front, Lesser White-front, Swan – look very much alike, and it takes experience to identify them by their calls and their shape and size. The black geese – Brent/Brant, Canada, Barnacle – show a little more variety, but there’s only one goose that really stands out for its striking plumage, and that’s the appropriately named Red-breasted. With its deep chestnut-red breast, exquisite head pattern and black and white body it’s an exceedingly handsome bird, and one that never fails to attract admirers when one turns up in Britain.

Red-breasted geese have always been rare visitors to the British Isles. The first record is of a bird shot in 1776, during a severe frost, not far from London. In the next 170 years there were just 13 records. These days sightings of these delightful geese have become much more frequent, and during most winters a few birds can be found in Britain. This current winter is no exception, and at the time of writing there are no fewer than five to be seen at four different locations.

Explaining the increase in the number of sightings is difficult, as the Siberian breeding population is declining. It might well be because there are far more people looking for unusual geese than was once the case, and most of them are equipped with the sort of optics that allow them to find unusual birds even at extreme range. According to the British Trust for Ornithology’s BirdFacts website, “Although a small number of vagrant Red-breasted Geese from the declining arctic Siberian breeding population winter in Britain each year, the species is popular in wildfowl collections and many birds are of captive origin. Vagrants are typically found in flocks of Brent Geese or Barnacle Geese so the winter distribution map mimics the stopover and wintering areas of those species.”

Red-breasts are indeed popular in wildfowl collections, but they are valuable birds that are rarely kept full-winged (it has been illegal for many years to keep them un-pinioned) so these days escapes are relatively rare. It’s usually easy to establish whether a goose is of captive origin, for it’s likely to be tame and approachable, and to appear in an unlikely setting, such as a town park. As the BTO notes, wild vagrants are usually found mixed in with Brent and Barnacle – both typical carrier species.

The immature Red-breast in my photograph is currently wintering at Cley, on the North Norfolk coast, where it’s become a popular attraction for the many birdwatchers. (You are likely to meet more serious birders in North Norfolk in one day than anywhere else in Britain, or anywhere in Europe for that matter). With so many people looking for it every day, it’s hardly surprising that its daily movements are monitored carefully. It likes to spend its mornings in company with several hundred Dark-bellied Brent Geese on what is known as the Eye Field, close to the sea.

Despite the fact that it is generally seen every day, finding it isn’t as simple as it may seem, and my first attempt, earlier this month, was a failure. It’s remarkable how as distinctive a bird as a Red-breasted Goose can disappear within a big flock of Brent, and it can take a lot of work with the scope to pick it out. My most recent attempt to see it, earlier this week, was relatively easy, as all I had to do was look for the small group of birdwatchers already watching it. Once I had joined them, picking it out was simple, but trying to spot it without binoculars, even at close range was still difficult. Despite its distinctive plumage, a Red-breast is surprisingly well camouflaged.

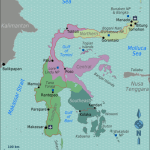

I was well aware of this, as I’ve watched flocks of Red-breasts in Bulgaria, a regular wintering ground for these geese. Here they are usually to be found with Russian White-fronted Geese, many hundreds of thousands of which winter around the Black Sea. In recent years the majority of the Red-breasted Geese have stayed in Romania, with much smaller numbers in Bulgaria. (Last year the peak count of Red-breasts in Bulgaria was 800, with 14,600 over the border in Romania). The Red-breasts tend to keep together, though within the White-front flocks, and it always takes some time with the scope to pick them out, even when there are hundreds of birds present. The photograph below was digiscoped in Bulgaria in February 2007. Most of the birds are White-fronts, but there are a few Red-breasts there, too (honestly!)

It is perhaps surprising that Branta rufficollis so seldom associates with White-fronts when in Western Europe. The very first Red-breast I saw was a young bird mixed in with Barnacle Geese at Caerlaverock on the shores of the Solway, in south-east Scotland. That was in October 1991. I’ve since seen individual Red-breasts in winter in the Netherlands (with Brent), in Estonia on spring passage (always with Barnacles), and on the Swedish island of Öland in autumn (again with Barnacles). I’ve also seen them in Greece twice: one sighting was a flock of nine birds at Lake Kerkini in January 2010, while a single individual I saw there in November 2017 was accompanying Russian Whitefronts (and not the nearby Lesser Whitefronts.)

The goose I photographed earlier this week is a first-winter bird: it shows five distinctive white bars on the closed wing – an adult would only show two. The breast is also a duller shade of red than that of an adult. Immature birds are more regularly recorded in Britain than adults, which makes sense, as they are, one suspects, more likely to get lost and caught up with flocks of Brent or Barnacles. Two years ago I photographed another Red-breast in Norfolk (below). This was also a bird that over-wintered and my photograph was taken at the end of its stay, in mid-May. It shows a distinct third wing bar, suggesting that it was probably a second-winter individual.

One of the attractions of wintering Red-breasts is that they usually become established in a relatively small area to which they remain faithful throughout the winter and well into the spring, finally departing with their companions (Brent or Barnacle) at the end of May. This makes then relatively easy for people to find. With luck I might well see the Cley bird again before it heads back to Siberia. It’s a goose I never tire of seeing.

For more information on the conservation of the Red-breasted Goose, plus stunning photographs of these birds, go to https://savebranta.org/en. These geese breed in arctic Siberia, and their migration route to and from their wintering grounds takes them through several countries, including Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine, making their conservation an international challenge. Stopping spring shooting and educating hunters about these endangered birds has helped reduce the pressure on the species, but many threats still remain.

Leave a Comment