New York City is full of surprises. For example, did you know that John James Audubon, you know, THE John James Audubon, the nineteenth-century painter of birds and mammals, the one with the birding and conservation organization named after him, has his final resting place in New York? Well, he does, and a recent visit there was well worth the long subway ride.

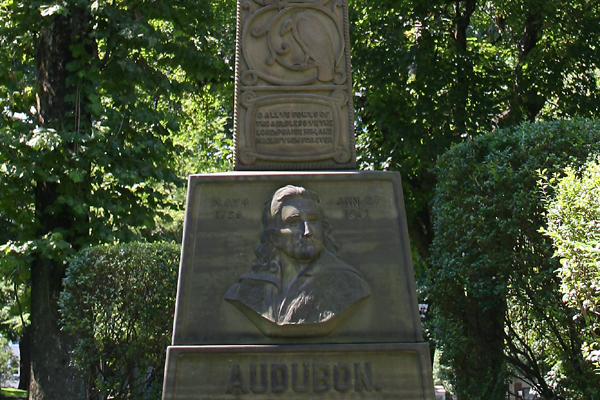

Audubon’s grave is in the Trinity Church Cemetery, on the south side of 155th Street, between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway. And while the monument is impressive and worthy of such an amazing naturalist and artist, the story of how it came to be is nearly as impressive.

For forty years after Audubon’s death, which occurred in 1851, the only marker on his grave was a simple stone that said “Audubon.” Eventually, in the 1880’s, Professor Thomas Egleston, a member of The New York Academy of Sciences, learned that Audubon’s grave might be threatened by the extension of a street. He convinced the church to move Audubon’s grave and in return offered to lead the fund raising for a monument suitable to one of Audubon’s stature. Egleston, in his eventual position of chairman of the committee charged with getting the monument built, rallied the scientific organizations of New York City and beyond, many of whom apparently agreed that leaving such a prominent naturalist without a proper monument was simply wrong. Even a committee of the American Academy of Sciences voted to support the monument-building, though they failed to follow through.

Even as money was being slowly raised the learned men of the monument committee, elected from several leading scientific organizations like The Linnaean Society of New York, The American Ornithologists’ Union, The Natural Science Association of Staten Island, the Torrey Botanical Club, the Manhattan chapter of the Agassiz Association, and the Audubon Society (it’s nice to see that all of the organizations but one still exist in one form or another today), were deciding on the design for the monument. By December of 1887, the basic design of a celtic cross was decided upon, a design for which it seems the Linnaean Society wanted to take credit. Though Egleston and The New York Academy of Sciences took the lead in the monument project each scientific organization wanted to be seen as the one doing the heavy lifting, and I imagine that this line in that short piece, “The monument, if placed in competent hands for revision and execution” must be a not-so-subtle dig at Egleston, and might be a result of the rather drawn-out fund-raising, which, by April of 1888, when the article was published, was rather short of the goal.

Egleston was so intent on seeing the monument built that he even used his house for at least one meeting of the committee. Despite efforts to raise the necessary funds in small amounts, he also (maybe at the urging of others on the committee?) started a century fund in December of 1890, into which wealthy men were encouraged to put $100 each. Excerpts from a letter to the editor of the New York Times, in which Egleston, who apparently thought that stretching the truth a bit was acceptable if it achieved the desired goal of getting the monument funded (he knew Audubon was not a native New Yorker, and also knew that Audubon’s grave was marked, albeit simply), are below:

…As he was by far the most distinguished naturalist that New York has produced, the scientific men of this city think that there should be erected some monument worthy of the eminent services which he rendered to science, and are endeavoring to raise money for that purpose…We are anxious to get subscriptions not only to this century fund but of smaller sums, to aid in the erection of the monument. It has been found impossible to make this a national movement. Will you not lend the infinence [sic] of your paper to the furthering of this object? It is certainly not creditable to New York that so distinguished a citizen should have no mark of any kind upon his grave.

The New York Times not only published Egleston’s letter to the editor but a couple of days later actually editorialized in favor of a monument to Audubon, even offering to accept donations which would be forwarded to Egleston! The editorial, though sometimes saccharine, is well worth a read and I highly recommend clicking through and checking out more than I have excerpted below.

The former half of the present century was remarkable for the number and excellence of the naturalists who sprang up in the United States. Among these JOHN JAMES AUDUBON will always be remembered by the people. He understood how to make science delightful to the “average reader” without impairing his own dignity as a man of science…Since AUDUBON’S day the grim spectre of the struggle for existence has risen beneath the Druidical pen of CHARLES DARWIN and thrown, it is much to be feared, a shadow on the scenes which our naturalist loved to describe as the joyous side of feathered life…We follow the assemblages of birds which seek mutual aid in companionship and, after some hours devoted to securing food, passing other hours in gambols which are the quintessence of free-hearted happiness. The same spirit of observing the joys of animals is one of the cardinal merits of AUDUBON…There is a park named after him but he deserves a statue. He was buried in Trinity Cemetery in 1851, but no shaft calls the attention of passers by to his grave.

The editorializing worked, and gentlemen with familiar names like Vanderbilt, Stuyvesant, Astor, and Rockefeller ponied up their $100 apiece at an alarming rate. By October of 1892 an article in the New York Times let readers know that the monument was virtually complete and would be ready to be erected within a month:

…a fourteen-ton block of North River bluestone, quarried in Malden Township, in the Catskills near Saugerties, arrived at the marble yeards of R.C. Fisher & Co…the stone has been cut into a monument in the form of a Celto-Runic cross…the cross is in one solid piece, 19 feet high, and weighs seven tons…The die [base of the monument on which the cross would stand] is a seven-ton block of bluestone, five feet high. The face has a heroic portrait of Audubon…this simple inscription appears on the base:

JOHN JAMES AUDUBON

Born May 21, 1780;

Died Jan. 27, 1851.

Erected by the American Association of Science.The monument was designed and modeled and the work upon it personally superintended by Eugene Pfister, foreman of R.C. Fisher & Co. Some of the minor work remains to be done but it will be ready to be unveiled in the latter part of November…This memorial…is in a measure due to the energy and zeal of Dr. Egleston of the School of Mines, Columbia College.

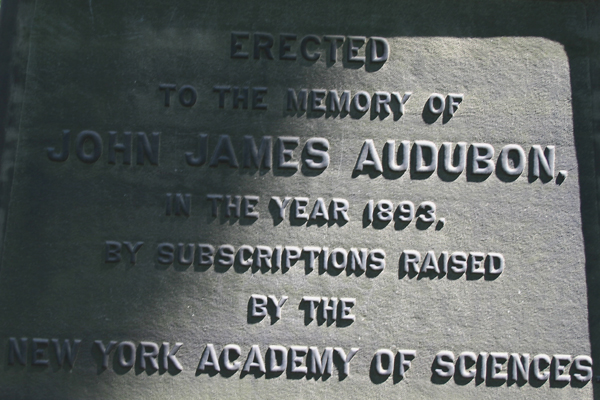

Unforeseen circumstances, the cracking of three consecutive dies (the base part of the monument), led to delays in the monument being unveiled. When it finally was unveiled, on 26 April, 1893, the New York Times reported that The New York Academy of Sciences had erected it and the inscription on the die of the monument said it had been raised “by subscriptions raised by The New York Academy of Sciences!” Now, granted, the leaders on the committee to get the monument built from the very start had been members of The New York Academy of Sciences, if any single organization deserved credit it would be the New York Academy of Sciences, and it made no sense for the American Association of Sciences to get credit for the monument but I imagine that members of, say, the Linnaean Society were kind of peeved! I tried to learn if the inscription was changed openly, as the result of a committee meeting, or clandestinely, by a partisan of the academy, but, unfortunately, I have not been able to figure that out.

Another mystery I would love to have solved, but that most likely never will be solved, is who decided that the first bird over the base of the monument on what is, in addition to being a monument, a grave, should be a vulture? Though Eugene Pfister is credited with designing the monument there was a subcommittee of the monument committee that decided on the birds and mammals to put on the monument. Was it dark humor that led to a vulture perching over Audobon’s body?

Regardless of who gets credit for the monument or who decided what bird went where the fact that a monument to John James Audubon exists in New York City is wonderful and I highly recommend a visit!

Information that helped me write this piece came from articles in the archives of the New York Times and from Transactions of The New York Academy of Sciences, which was helpfully pointed out to me by Bill Silberg, Vice President for Publishing and Communications for The New York Academy of Sciences. By the way, that link to the Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences is well worth the click through for anyone who wants to learn more about the monument-building process: not only does it go into excruciating detail, but it also includes the text of speeches in support of the monument, some not-very-accurate biographical information on Audubon, and a full list of all donors to the monument committee.

To get to the Audubon Monument take the 1 train to 157th St or the C or B-D train to 155th St and walk on 155th St to the south side of the middle of the block between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave. The monument is easily visible from the street, and one may enter the cemetery by a gate directly in front of the monument.

Cracking article Corey, well done!

can’t wait to see u today yayyyy

Thanks. An interesting story I would have otherwise not known.

What is the inscription below the vulture? (Was that in the article and I just didn’t catch it?)

Definitely one of your best post (now, what does that mean 😉 )

Have your dropped Laurent a comment yet?

@Charlie, Jochen: Thanks! (And, yes Jochen, Laurent and I are in touch…thanks some more!)

@Raven: I’ll see you this evening!

@Bosque Bill: You didn’t miss it, I left it out! The inscription reads “O, all ye fowls of the air, bless ye the Lord; praise Him and magnify Him forever!” On the back side (where mammals are carved) is a similar inscription but relating to beasts.

Thanks, Corey, my curiosity about the inscription had been really itching! Now, suitably scratched.

Great sleuthing, Corey. Glad you enjoyed the (my) neighborhood; come back again. For more information on Audubon’s monument, a list of the MANY people buried with him, Trinity Cemetery where he’s buried, and Minnie’s Land, Audubon’s farm that once occupied the northern side of 155th Street across from the monument, see the links at the end of this post.

The vulture? During his lifetime, Audubon involved himself in a great debate about vultures: did they “spot” carrion from the air by sight or by scent? It was a cause celebre in scientific circles. My guess is that the gentlemen who designed the monument included the vulture both out of respect to Audubon and with a certain sense of humor.

When the monument to Audubon was unveiled, the city’s intention was to extend Audubon Avenue south to 155th Street (from 165th) so that it would begin in front of the monument. Unfortunately, after consolidation of the city in 1898, funding wasn’t available and that plan never happened.

Audubon Park: http://www.audubonparkny.com

Audubon Monument: http://audubonparkny.com/AudubonParkAudubonTomb1.html

Trinity Cemetery: http://audubonparkny.com/AudubonParkTrinityCemeteryTour.html

Interesting post and excellent researching! I would agree w/ MatthewS about the vulture; Audubon’s first presentation to a scientific group was about vultures in Edinburgh, Scotland. I also noted the shotgun carving on the monument. Many of you probably know that he shot his avian subjects in order to draw and paint the birds from up close. (And he ate some of them, too!).

The farm on which he grew up (but he wasn’t born here) is Mill Grove, located very close to Valley Forge, PA. I learned about JJA from Richard Rhodes’ biography of him, a very good and interesting read.

Hi Corey, MatthewS pointed out your interesting post to me. Impressive research!

Just to add to the discussion on the vulture, the bird on the monument is based on Audubon’s painting (and prints) of the California Condor, which Audubon called the California Vulture. It is definitely taken from Audubon’s art, whereas most of the other birds are not recognizable (to me at least) as Audubon’s work. The California Condor being a western bird, Audubon never saw it in the wild, and never saw any live specimens. The experiments with vultures (conducted with the assistance of John Bachman who published on the subject in 1834) were limited to Black and Turkey Vultures. I am personally inclined to think inclusion of this bird was more of a nod to death, not to Audubon’s experiments.

I have photos of the monument on my website (link below) with transcriptions of the inscriptions. The inscription on the bird side reads, “O ALL YE FOWLS OF THE AIR, BLESS YE THE LORD, PRAISE HIM, AND MAGNIFY HIM FOR EVER.” The other side of the cross includes some animals (some based on Audubon’s work, some not). On the side of the cross showing mammals, there is a variation: “O ALL YE BEASTS AND CATTLE, BLESS YE THE LORD, PRAISE HIM, AND MAGNIFY HIM FOR EVER.”

http://www.minniesland.com/about_our_name.html

Thanks for the excellent research. I discovered Audubon’s grave marker before I discovered your blog post. Your research answered almost all the questions I had. Here is a link to my post where I also link to your blog in general and this post in particular. http://summittoshore.blogspot.com/2010/05/celtic-cross-for-birds.html

Being far away from America, we birders in India are continuously reminded of Audubon’s legacy. This little vignette should emphasize his magnificent presence in our imaginations.

Over at The Green Ogre, we made a different connection. Birds, we thought, have always awakened the poet in the artist and the artist in the poet. Emily Dickinson, Audubon’s contemporary, may never have met the great bird artist but in some of her poems it is possible to visualize the same power of inspiration that drove Audubon to render his magical brush-strokes.

I recently visited Audubon’s grave and the birth date engraved on the monument says May 4, 1780, this date is incorrect and needs to be changed. The monument could also use some cleaning up!

Francis, May 4, 1780 is the date that JJA gave most often as his birthdate and the date his biographers (and his family) accepted, until Herrick published his seminal Audubon autobiography in 1914, after monumental research. Even in 1905, one of JJA’s granddaughters helped plan a celebration marking the 125th anniversary of her grandfather’s death: wrong day, wrong month, and wrong year.

An interesting coincidence, though: the 1893 dedication of the monument took place on April 26, Audubon’s actual birthday, apparently unbeknownst to anyone attending.

Matthew, so if May 4, 1780 is the birth date accepted by his biographers and family, then any mention of April 26, 1785 needs to be correted!

@Francis: I think what MatthewS is saying is that what the family and early biographers thought was correct turned out to be wrong. His actual birthday is 26 April 1785.

@Corey: Is there any physical evidence that proves JJA was born 26-Apr-1785, or is that date accepted by a majority of people?

Maria Rebecca Audubon published “Audubon and His Journals” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897). On p. 6, Vol. I, “…the date of Audubon’s birth is not known, and must always remain an open question. In his journals and letters various allusions are made to his age, and many passages bearing on the matter are found, but with one exception no two agree; he may have been born anywhere between 1772 and 1783 , and in the face of this uncertainty the date usually given, May 5, 1780 [SIC], may be accepted, though the true one is no doubt earlier.”

Fransic, As I wrote in a previous post, until Herrick researched primary (original)documents while preparing his 1914 Audubon biography, the accepted date among biographers and JJA’s family was May 2. Check the Audubon biographies by Herrick, Alice Ford, and Shirely Stevshinsky for their methodology in determining JJA’s actual birthdate. The were systematic and thorough.

Take care when using Maria Rebecca as a reliable source. She is infamous among Audubon scholars for re-writing her grandfather’s journals and then burning the originals, in the process, destroying valuable source material, only because it did not fit with the image of her grandfather she wanted to portray.

one image of the monument depicts two birds: a goose-like creature and a spoonbill. it should be noted that the spoonbill is not a Roseate Spoonbill as drawn by JJA. I believe it is an African species.

I listed a scarce Audubon Monument Committee report on ebay under user “mpemj”