I often wonder how many birds I would see if I spent a whole day sitting in the garden, watching the sky. What is certain is that a lot of birds slip over unseen, though just occasionally I spot something unusual. This happened on Tuesday, 16th September. A friend staying with me remarked on the number of Blackbirds in the garden. I looked out to check on them (my maximum count had been 11) and happened to glance skywards. There, flying in a straggly line overhead, was a flock of large black birds.

A flock of Glossy Ibises

I was pretty sure what they were – Glossy Ibises – before I’d even reached for my binoculars, which I keep handy in the kitchen. However, the view through the binoculars confirmed that these birds were indeed Glossy Ibises, readily identified by their shape – they are broad winged with long beaks – and their style of flight. They are birds I am familiar with, having seen them many times in places like Portugal, Spain and Greece, as well as Africa and America, for they are a cosmopolitan species. A quick count before they disappeared from view suggested that there were at least eight of them, and possibly 10.

The Glossy Ibis has a highly distinctive flight silhouette

Glossy Ibises are rare birds in England, so such a sighting would have been improbable except for one fact: September witnessed the biggest-ever recorded influx of these birds to the British Isles, when more than 400 were counted at a variety of locations. I just happened to be lucky and see these birds flying over. Interestingly, a flock of eight were recorded flying over Cley in Norfolk that day. Could they have been the same birds I saw? The chances seem highly likely. (Cley is 50 miles directly north of my house).

These ibises had almost certainly flown north from Span and Portugal, where the population is numbered in thousands of pairs. Intriguingly, they died out in Iberia in the 19th century. There were a few sporadic records in Spain during the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, but then observations became more frequent, with the first nesting taking place in the Coto Doñana in 1996. By the start of this century big colonies had become firmly established not only in the Doñana, but also in the Ebro Delta and around Valencia.

Since then they have spread to Portugal and France, though it wasn’t until 2022 that there was the first successful breeding record in Britain (in Cambridgeshire). My guess is that some of the birds that reached us in September will remain during the winter, and that there are likely to be more breeding attempts in the spring of 2026. It even seems probable that Glossy Ibises will become common breeding birds here, establishing themselves in East Anglia just like Spoonbills, Little, Cattle and Great White Egrets have done already this century.

This individual shows how the Glossy Ibis acquired its name

Little Egrets first nested in England in 1998: they are now common and widespread, and can be found throughout much of the British Isles where suitable habitat exists. Pure white, with a long black beak and legs, the only touch of colour they have is their bright yellow feet.

The Little Egret is very similar to the closely related Snowy Egret of the Americas

Great White Egrets are much bigger birds. They first nested in England, in Somerset, in 2010, but they are also increasing rapidly, and I now see these birds regularly. Cattle Egrets are another recent colonist. Like the Great Egret, the adults also have yellow beaks, but they are much smaller birds, so there’s little chance of confusing the two. They first bred in England in 2008; they have been slow in establishing themselves here, though numbers are now increasing. As their name suggests, they do like to feed with cattle, but sheep, goats or horses will do if need be.

Great White Egret: now a familiar bird in many parts of England

Quite why they have been so slow to become established is a bit of a mystery, for this is one of the world’s most successful birds, increasing its range hugely in the last 100 years. It’s thought that this egret has its origins on the plains of the African tropics, where it remains a familiar species. The first sighting in South America was in 1880, with subsequent records in 1911 and 1913. By 1937 it was thought to be breeding in Columbia and Guyana.

Cattle Egrets do live up to their name. This flock was photographed on the Balearic island of Menorca, where they first nested in 2006

They invaded Central and North America using two routes, with birds coming via Columbia to Middle America and via Trinidad and the Antilles to the eastern USA. By 1956, within five years of their arrival, they were established from Texas to Boston, though few had nested away from the coast. Four years later they had reached Canada and were breeding far inland.

In Europe the Cattle Egret has expanded its range north and east in the last 30 years

In Europe the species was once restricted to the south of Spain, but its range has expanded considerably in the last 50 years, spreading north to France and east to Italy. A serious drought in Spain led to a big influx of birds to France in the early 1990s, while the first breeding attempting in Holland was in 1998. Apart from climate change, intensification of agriculture and the spread of irrigated crops are both factors that are thought to have helped this range expansion.

Cattle Egrets have short yellow beaks

Here in Britain their colonisation has been slow, and the number of nesting pairs is probably still fewer than 100. However, last winter up to 700 birds were counted roosting on the Somerset Levels, so there’s little doubt that these small herons are here to stay, and it even seems likely that the Cattle Egret will eventually becomes our most common species of heron.

Your comment regarding the apparent slow spread in the UK of the Cattle Egret is paralleled here in New Zealand. Despite the rapid increase in range and numbers seen elsewhere the species has been slow to establish here and is rarely seen in much of Northland, in the North Island, despite the large number of cattle here. It is another intrigue in birding in Aotearoa.

The photo of the single ibis flying overhead made me want to look very closely. Especially flying overhead, important field marks are difficult. Where I am from, ibis flying overhead can only be ID’d as Ibis sp. or Plegadis sp. Well, at least there was one time when I was called out. I thought the single ibis could be a White-faced ibis. But then the sun on the feathers can sometimes make things appear differently than they really are.

The photo of the ibises all jumbled up is wild.

David’s comments about the fate of the Iberian ibis are hard to believe when you look at flocks of thousands of ibisies flying over the lezirias in Lisbon. However, it is a shocking truth and a clear warning that abundance may not last (but can be regained).

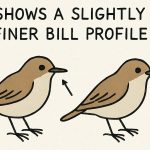

White-faced Ibis has yet to be recorded in Europe, so this isn’t a bird we really have to consider this side of the Atlantic. My ibis photographs were taken in Portugal, Spain and Cyprus.