Two epigraphs open Bernd Heinrich’s White Feathers: The Nesting Lives of Tree Swallows, each so redolent of his work as a whole, not just this new book, that they deserve to be quoted, even in a mere review, in full. The first is from the American naturalist William Beebe:

“I was walking across our compound last month when a queen termite began building her miraculous city. I saw it because I looked down. One night three great fruit bats flew over the face of the moon. I saw it because I looked up.”

Heinrich is prolific, but everything he writes is worth reading. In most every one of his books (or articles, like those that were collected in his last book, A Naturalist At Large) he poses a question about the natural world — often a question, like the central one in White Feathers, that no one else has thought much about — and then solves it. (Or sometimes not — but even his wrong turnings are interesting.)

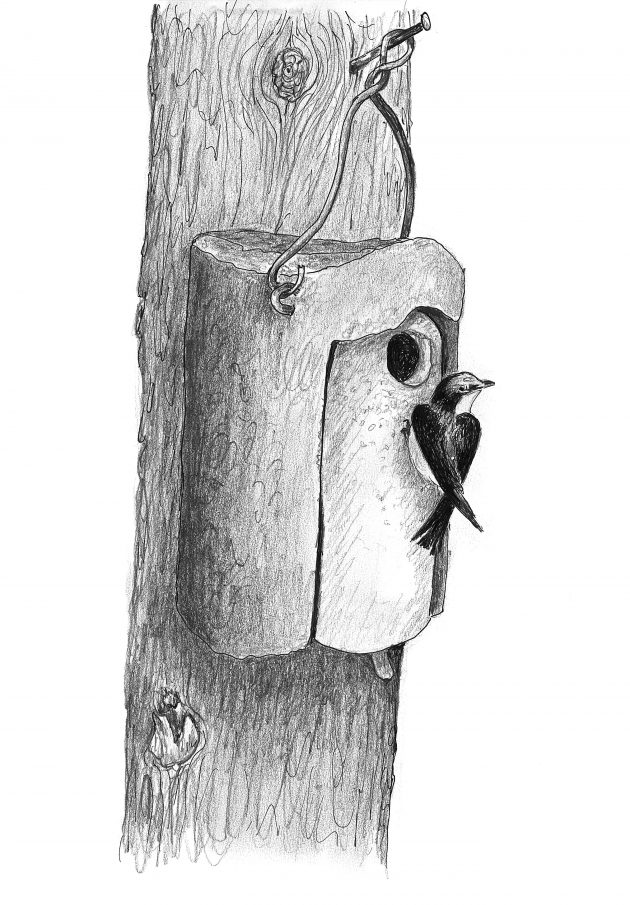

Here’s the question in this book: Tree swallows build their nests in tree cavities or manmade boxes. Why do they gather feathers (duck feathers or others, white or sometimes otherwise) to line the nests– and place the feathers in a sort of canopy over the nest, like a parasol with a hole in the top?

Heinrich never answers the question definitively (but then lots of questions about bird behavior don’t have definite answers, not to us). His first surmise seems like a good one – that the feathers are meant to hide the eggs from other female swallows seeking to parasitize the nest, by disrupting the parasite’s timing (if eggs are present, the parasite would know that the nesting mother is ready to incubate – that is, incubate not only her own eggs, but the parasite’s, as well).

(There’s a remarkably similar photo, of the nest of a west coast swallow, the Violet-green, in this July 2014 post (the third photo down.))

Other explanations, arrived at much later (this book covers Heinrich’s observations over ten nesting seasons), include that the feathers might be nuptial gifts from male to female, or, simply, toys – as when the female grabs a feather from the ground, flies into the sky and circles with it, then drops it, only to pluck it out of the air and repeat the maneuver – ten times.

That notion of play in birds reminds the reader that one of Heinrich’s best attributes as a writer and naturalist has always been his willingness to commit anthropomorphism (or, as he calls it elsewhere, perhaps with the slightest hint of derision, “APM”), gladly and without apology, but with, usually, an explanation of the scientific rationale for the behavior. It’s not out-of-bounds, to him, to ascribe such things as emotion or feelings to animals (indeed, it’s a naturalist’s requisite): “Like other physiological mechanisms, these are shared among species and can be assumed to be present in others, just as we may assume every vertebrate animal has a heart, a brain, lungs, liver, and alimentary canal.”

Heinrich is fond of, and indiscriminate in, the use of the word “cuckold” and its inflected forms to mean . . . what, exactly? That’s the problem. A cuckold is a male whose female mate has sexual intercourse with another male. Othello thought he had been cuckolded by Desdemona and her supposed lover Michael Cassio.

But Heinrich uses the term to mean (probably) that a strange female has laid her egg in a nest she did not make – a la the cowbird or cuckoo. Or maybe he means that a strange female has mated with the main couple’s male (swallows are frequent copulators – fifty times per clutch – and promiscuous, too). Who knows?

He has employed this usage this for years, as in his 2010 book The Nesting Season: Cuckoos, Cuckolds, and the Invention of Monogamy (where he previously pitched his white feather hypothesis, in abbreviated form) — and of course he’s Bernd Heinrich, a naturalist of deserved renown, and entitled to semantical latitude. But why create the confusion at all? There’s nothing wrong with the standard “brood parasite” or, if you want to get fancy, “inquiline.”

He can be confounding in other ways, too, when he fails to tie up loose prosaic ends. After telling, early in a chapter, of a pair of swallows that had ejected a chickadee hatchling from their nest, he concludes by saying that “the only possible nest parasites that swallows need to watch for” are cowbirds and other swallows. (What about that chickadee?) And, though swallows are “well-known to nest near each other,” he never expresses much wonder at why, of the nine nest boxes in his lot, only one is ever occupied during the ten years. (He does, though, offer a hunch – that the resident pair are “protecting sky space.”)

But two things make every Heinrich opus worth reading and, mostly, delightful – his patience and his experimental method.

Patience: Nothing in the natural world seems to escape Heinrich’s notice, and this is not surprising given his ability to stick to his task. From one dawn until 4:20 p.m. (for only one example) he jotted down 410 separate behavioral acts – despite being tortured by the horrid black flies of Maine (where he has a cabin, and whence his observations come).

Method: he “tames” the swallows, when they first arrive in the spring, before they can find in him any cause for alarm:

“I intended to teach the swallows that I was like any other feature of this landscape, like the post, the solar panel, or the apple tree. I would then become invisible to them, and their activities would be unaffected by my presence.”

And it works! He can touch their tailfeathers without flushing them, and “feed” them feathers from his hand:

“Not to be confined by the greatest, yet to be contained within the smallest, is divine.”

(That’s the other epigraph, in addition to the William Beebe quotation at the top of this review. It’s from St. Ignatius of Loyola and, in this context and for this book, is a perfect fit, as well.)

Every Heinrich book makes one envy his ability to observe closely – to read a piece of nature like the close reading of a poem. What one would give to walk the woods with eyes as acute as his, and curiosity as unceasing!

White Feathers: The Nesting Lives of Tree Swallows, by Bernd Heinrich / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 232 pp., $27 / February 18, 2020 / ISBN 978132860441-5 (hardcover) / ISBN 9781328603517 (ebook)

Leave a Comment