Turning off the asphalt, I enter the Deliblato Sands steppe, between the Danube and the Carpathian Mountains in the northeast of Serbia, where the first bird to greet me is a Northern Wheatear, followed by a Crested Lark. The wires are decorated with only about a dozen European Bee-eaters: is it still too early, or has the local colony dwindled?

Deliblato Sands comprises an elongated elliptical tract of sand, spreading north from the Danube, about 35 km / 20 mi in length and 15 km / 10 mi in width. Dominant easterly winds have shaped the prominent dune relief rising from 70 m / 200 ft a.s.l. (the altitude of the Danube) up to 200 m / 650 ft a.s.l. Continental climate and the absence of surface water took care of the rest.

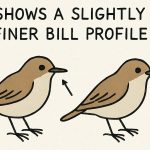

In front of us, the dirt track is cut deep into the aeolian dune overgrown with feather grass (Stipa joannis) with its fronds seductively glistening in the sun. A small bird lands at the tussock at the edge of the track: slim, longish tail, sandy-coloured with unstreaked buff-white underparts. The only unstreaked pipit around here and a characteristic breeder of sand dunes is the Tawny Pipit and this one shows well, holding to the grass edge.

Two European Rollers await us on the wires, while one Eurasian Hoopoe flies by. On the opposite side is a smallish falcon, obviously too short-tailed for a Common Kestrel, a Eurasian Hobby first comes to mind… but a male Red-footed Falcon on migration it turns out to be. They do not build nests, but occupy old nests of Rooks and breed colonially among them. Red-footed Falcon’s breeding range starts less than 50 mi north of here and I hope that some will choose to join a local rookery and stay.

A pair of European Turtle Doves on a wire, followed by two soaring Common Buzzards…. Wait, those fingers, the upper one is not a buzzard… a small eagle, it’s a dark morph Booted Eagle! They are quite a rare breeding species in Serbia, declining as we speak, but one pair breeds nearby. Yet, when I visit the area, a sighting is far from a common occurrence.

Wandering through the short grass, there’s a flock of Sand Martins (a.k.a. Bank Swallows) – in 1990s, their local colonies along the 10 km long section of the Danube riverbank summed together reached 15,000 active nests, but that number is now lower. One harrier in flight, a female Montagu’s Harrier, and a male is nearby! They are rare breeders here, but at least, this species’ numbers are on the increase.

Female Montagu’s Harrier at Deliblato Sands, by Aleksandar Urosevic

Female Montagu’s Harrier at Deliblato Sands, by Aleksandar Urosevic

Some nice birds indeed, but let’s look back and ask ourselves not what have we seen, but what we haven’t? There wasn’t a single European souslik or ground squirrel (Spermophilus cittelus). 11 years ago, alongside my bird notes I wrote of numerous sousliks observed along this same route. Two years ago for the first time I noted that not a single souslik was seen, and it hasn’t been seen ever since. Add into that picture that the last time I observed the endangered Saker Falcon in Serbia was here – but three years ago, when squirrels were still present.

The story is even worse with the vulnerable Eastern Imperial Eagle. In order to prevent sand storms choking nearby villages, from 1818 to 1907, half of the sand dunes surface was afforested, mostly with pine (until the disastrous forest fire of 1953) and non-indigenous false acacia. Today the stands of acacia occupy one third of the nature reserve. Tasty sousliks lived along the edge of this odd forest. Hence, it comes as no surprise that this area was one of the last strongholds of Imperial Eagles in the country (6 to 7 breeding pairs up to the mid-1980s). The last time I observed an Imperial Eagle here was in 2007, but that was a non-territorial, immature bird. There are no breeding pairs left in this forest and nowadays we have only one left in the whole of Serbia.

I must digress further. Taking part in a wind farm development workshop in the Serbian Chamber of Commerce, I learned that no less than 8 construction permits are issued and that the Deliblato Sands should become encircled with wind generators from all sides. On that occasion, a raptor expert Sasa Marinkovic raised an important and still unanswered question: How should we treat a locally extinct threatened species in a wind farm environmental impact assessment? The EIA methodology says nothing about it and yet, if ever a reintroduction of this species should be attempted, this nature reserve makes an obvious location choice.

At the time being, no eagles were recorded within the EIAs made for the proposed wind farms, which, I am sure, made the process of obtaining a permit much easier. The construction has started and I am afraid that we are all at loss because of it.

Cover photo: European Bee-eater at Deliblato Sands, by Roksana

Leave a Comment