British birders are very serious about birding and their birds. This is a very good thing; it means they publish a lot of books about birds (probably more at this point than U.S. publishers); they host something called a Birdfair that maybe someday 10,000 Birds will send me to visit; they produce outstanding birders, some of whom come over to the U.S. and share their expertise, or do big years or write excellent blog posts.

It also makes it a little intimidating to be doing a review of Britain’s Birds: An Identification Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland. This photographic guide by Rob Hume, Robert Still, Andy Swash, Hugh Harrop, and David Tipling was ten years in the making and is spilling over with photographs and identification-type information, giving weight to the claim that it is a “complete and authoritative photographic guide to the wild birds of Britain and Ireland” covering “all plumages likely to be recorded of every species accepted onto the British and Irish lists up to the end of March 2016, including rarities” (Introduction). The book is produced by WILDGuides, Ltd, the excellent book company responsible for over a dozen photographic guides on Britain’s natural life ranging from dragonflies to plant galls as well as books on Africa, Australia and other areas we all want to visit, and was published this summer by Princeton University Press. Britain’s Birds was released at Birdfair, and caused a bit of a stir, positive and negative. Like I said, Brits take their birds, and apparently their bird guides, very seriously.

This is a hefty book, 560 pages long and dimensions of 6.3 x 1.6 x 8.46 inches, which makes it just a little too large to be a field guide. It does fit into a medium backpack (though keep in mind that it’s heavy, almost 3 pounds) and definitely onto the backseat of a car. It is made for wear and tear, with a flexibound cover and binding that allows you to see both pages clearly without breaking the spine.

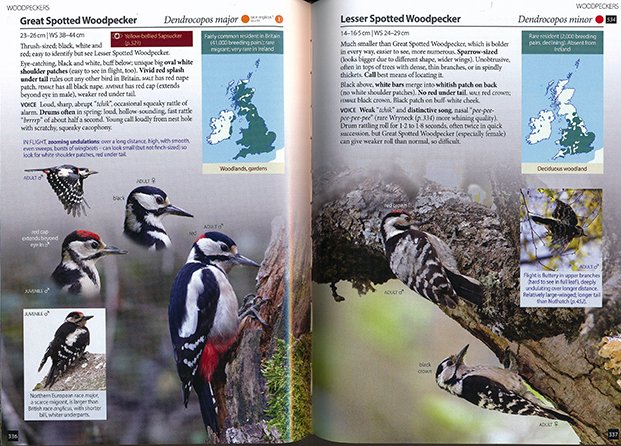

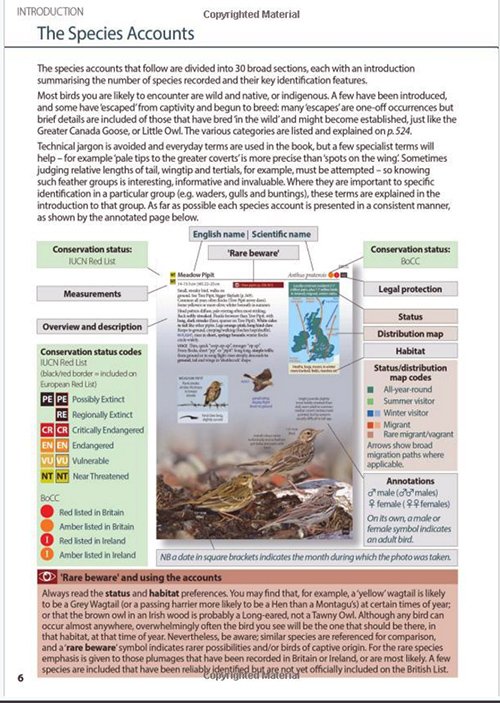

The design focuses attention on the photographs. Over 3,200 photographs have been used, most showing species in their habitats. There is also text, distribution maps, a dark red bar “warning” about similar looking rare species, and conservation symbols. There are comparative flight layouts, tables comparing subspecies characteristics, timelines of gull molt, comparative bill close-ups, boxed photographic inserts, and comparative wing drawings. It’s a busy book with a crowded sense of design, and though I love all the different kinds of information offered in so many ways, there were times I longed for a little black space.

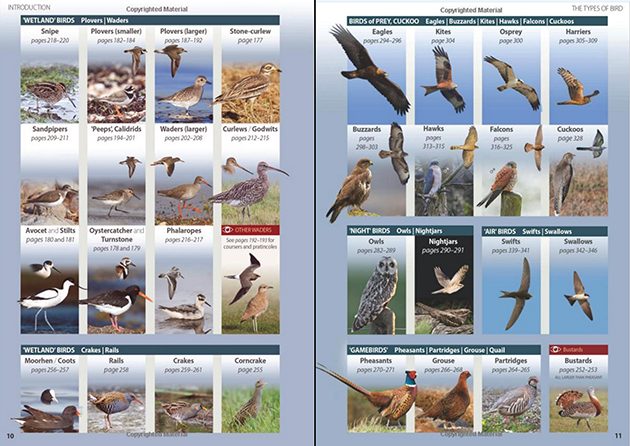

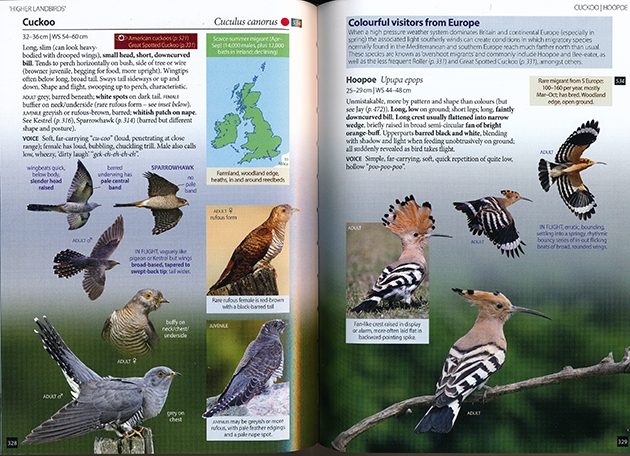

Britain’s Birds is organized in a very loose taxonomic order, with priority given to grouping together birds that are perceived as similar. There are 28 chapters—“Waders,” “Large Waterside Birds,” “Owls and nightjars,” “Birds of prey” (pulling together vultures, hawks and falcons), “Aerial feeders” (swifts, swallows, martins), etc.—plus a chapter on “Vagrant landbirds from North America.” Birds that are not easily grouped with others are put together in what I call the fun groups: “Dippers, Wren, accentors, oriole, starlings and waxwings” and “Kingfishers, cuckoos, Hoopoe, bee-eaters, Roller and parrot” (which are actually related, the authors tell us, as they are mostly “higher landbirds”). The book’s organization reflects the authors’ goal of making this a guide accessible to birders of all levels and skill. My librarian self is partial to a more strict taxonomic organization, but with no hope that the constant shifting of families will end in the near future, this type of sequence is making more and more sense.

So, how do you find the species account for Kestrel if falcons are not placed between woodpeckers and parakeet? You can check the table of contents, or browse the “gallery of thumbnail images” in the Introduction (see image above) or use either of the two indexes—a Short Index on the inside back cover flap and a traditional Index of popular and scientific names. Browsing is facilitated by section titles at the top of each left-hand page and smaller group titles on the upper right-hand page. I was wondering if a colored tab system would have been a good addition, but decided that it would just add a confusing element to a book that is already visually busy.

Unlike many other identification and field guides, Britain’s Birds has a very brief introduction, focused on the contents of the book and how to use it. Novice birders will have to look elsewhere for tutorials on the overall process of bird identification, diagrams of bird anatomy, or outlines of British and Irish habitat diversity.

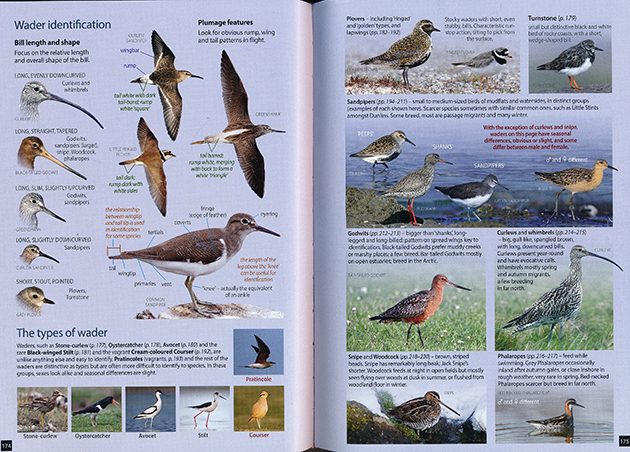

The chapters, however, offer very good introductions to each bird group. The 4-page introductory material to “Waders,” for example, discusses factors to keep in mind when identifying shorebirds (breeding and nonbreeding plumage, age, migration timing, molt), gives examples of diverse shorebird bill lengths and shapes, delineates the anatomy of the shorebird, and succinctly describes the common characteristics of subgroups (plovers, turnstone, sandpipers, godwits, curlews and whimbrels, snipe and woodcock, phalaropes). Not all of the chapter introductory material is this extensive (let’s face it, shorebirds are a challenge in any country), but they do all list what features to look at for identification (size, leg length and color, bill length and shape for waders, a much longer list for gulls) and subgroup descriptions. The latter will be useful, I think, to novices and visitors to Great Britain. I found it interesting, for example, to learn that tits movements differ from warblers, that they “have a bolder, more stop-start or leaping progress through trees or across spaces.”

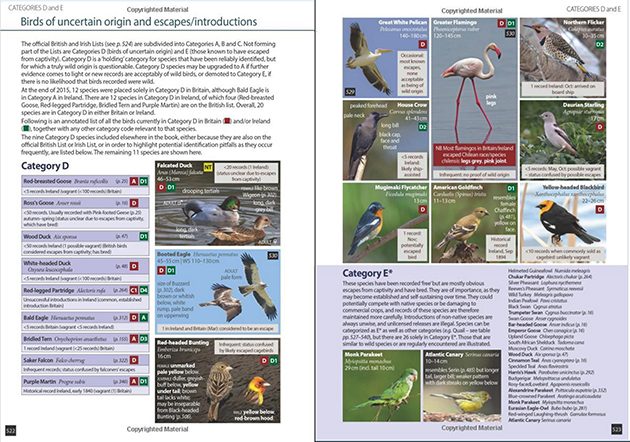

The book’s organization of rare and vagrant birds is inconsistent and confusing. They can be found all over the book–some interspersed with resident and migratory species, some collected together in the back of the chapter, some in the last chapter on North American vagrant landbirds. How does a birder using this guide for the first or even tenth time know where to look, especially if you know you are looking for a rare bird, but are not sure of the name? I ended up flipping through the pages, looking for entries that did not have a distribution map. Noting the rare and vagrant sections in the table of contents or adding specialized index would greatly help accessibility.

Roughly 236 species receive the full species account treatment–a page (sometimes two, sometimes a bit less) featuring photographs of the species in all plumages; common and scientific names; measurements; indicators of conservation status and legal protection; the “watch out for this similar looking rare bird” bar-with-eye; a paragraph or two of text describing the bird’s appearance and behavior, with important diagnostic features in bold print; a brief description of the bird’s song and call including sound transcriptions; a distribution map with the bird’s status (resident, migrant, vagrant, rare, etc.) and population estimate above the map and the bird’s most likely habitats below the map.

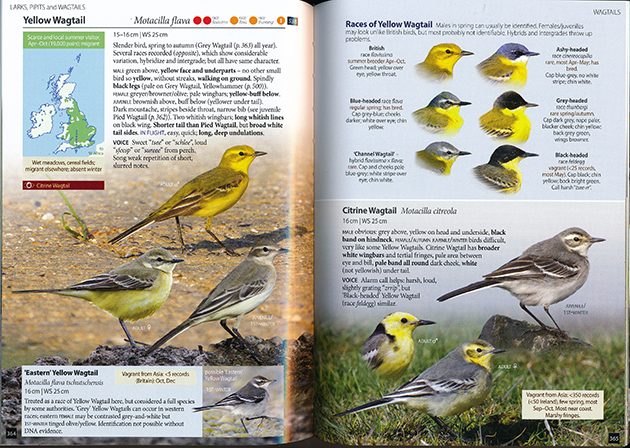

Photographs are annotated for age and gender and, if appropriate, for subspecies. Identification clues are also given–flight description, diagnostic features, behavior to watch for, plumage variability. The text and photographic captions usually complement each other, so both should be read. The maps are problematic. I compared a random sampling to the bird atlas maps offered on the BTO (British Trust for Ornithology) web page and found inconsistencies, perhaps because the book’s source was BirdLife International. Also, not all maps show migration route arrows and notes on places from where and to the birds migrate are either missing or hard to read.

Coverage of rare and vagrant birds is extensive. Some birds, like this Hoopoe above, receive almost as much coverage as commonly seen birds, minus map and conservation symbols. Other species, like our North American land birds, receive cursory treatment–a photo, measurements, a sentence and some captions on diagnostic features. This makes sense, since most of these birds have at the most 30 records in the area. There is even a short section on “Birds of uncertain origin and escapes/introductions,” which in British bird terms are the Category D and E birds.

There is extensive coverage of subspecies, as this plate of Yellow Wagtail shows. Not only are the different races pictured, the different conservation statuses of each race are indicated at the top of the page.

Over 251 photographers contributed images, including four out of the five authors. The photographs are fully credited in the back of the book, with both a listing of all photographers and a page-by-page, species-by-species listing of who took which image. The quality is overall impressive. And, care has been taken to position the photographs so all the birds on a page are facing the same way, which makes it easy to compare plumages and structural features.

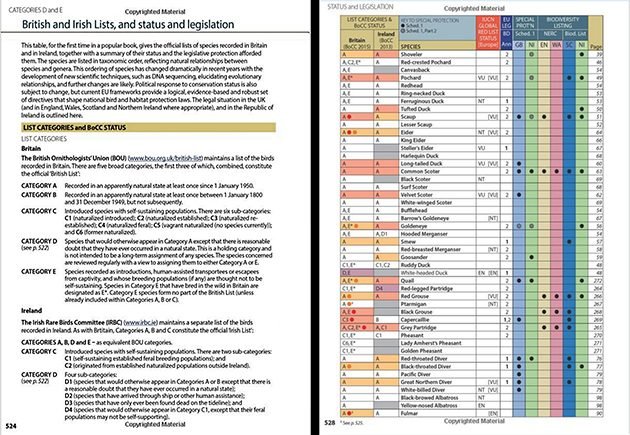

One unusual feature of this guide is the back-of-the-book section on “British and Irish Lists, and status and legislation.” This complicated table lists all British and Irish birds in taxonomic order, indicating their status on the Bird Lists of Britain and Ireland (the lists are divided into alphabetical categories from A to E), their conservation status according to the IUCN Red List, their special protection status under Irish, British, Scottish, and Welsh law and biodiversity plans. I don’t really understand why this 15-page section is included in a book already bursting at the seams. Conservation is, of course, very important, but the species accounts already indicate this information. I imagine that it’s a product of the authors’ concerns, but I don’t think it contributes to identification skills or knowledge base.

The authors themselves–Rob Hume, Robert Still, Andy Swash, Hugh Harrop, and David Tipling–collectively have 100s of years of birding and photographic experience. Rob Hume is a writer, editor, and tour leader; Robert Still is co-founder and publishing director of WILDGuides, with a specialty in design and computer graphics; Andy Swash is managing director of WILDGuides, author, co-author, and editor of many of WILDGuides books, and a photographer and co-owner of a photographic nature agency; Hugh Harrop in a nature photographer and founder of a nature tour company called Shetland Wildlife; David Tipling is a well-known nature photographer and the author or commissioned photographer of over 30 books, including Birds and People (2013). I wish they had provided more background on how this guide came about and what each of their contributions was.

Up to this point, I’ve been reviewing Britain’s Birds as a librarian, looking at organization, design, and accessibility of information in a book format. There is an important area I haven’t touched on yet—accuracy of visual content. Is the bird pictured what the caption says it is? I discovered very much by accident that questions have been raised by British birders about the accuracy of some of the book’s photographs; this is the to-do at Birdfair I referred to in the beginning of the review. A small number of photographs were cited on social media sites (Facebook and a birding forum) as incorrectly captioned by species, and more photographs were cited as incorrectly labeled for age or plumage.

This is disturbing. I looked at the specifically cited examples of species misidentification and though there are a couple that appear valid (the head of the juvenile Little-ringed Plover on page 182 is that of a Ringed Plover), I’m not so sure of others (is the image of the juvenile Audouin’s Gull on page 139 truly that of a Yellow-legged Gull or a bad photograph?). Several of these claims are about very similar species, such as Common and Spotted Sandpiper.

It’s not clear if the social media finger pointing comes from birder enthusiasm (after all, the authors do ask in the Introduction that for user feedback on “errors and omissions) or a reaction to the marketing claim that the book covers ALL plumages (capitals my own). Certainly, some of the accusations seem more in the realm of gossip than constructive critique.

At the same time, I don’t find it surprising that a guide with so many authors and so many photographs would have inaccuracies. I think that field/identification guides by one or two authors (think Sibley’s, Nat Geo, Stokes) are simply more likely to be accurate because there is one (or two) minds in charge. They tend to be more unified in design and organization. I’ve done things by committee, and even with the most well-intentioned members, details are dropped and lost and corrections are placed in the wrong file or on the wrong draft.

It would be very helpful if the authors or publisher posted a public response. In the meantime, the fact that the book has been reduced in price from $35 to $21 lends credence to a theory that the publisher is trying to sell all copies so they can produce a corrected second edition. (PUP and authors—if I’m wrong, please let me know!)

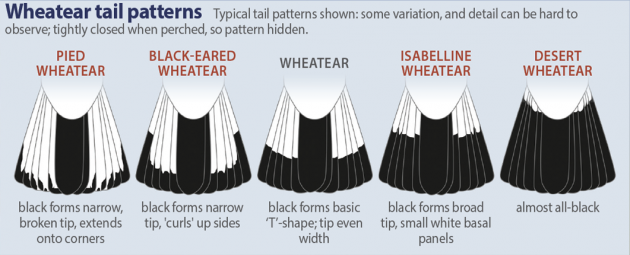

I find this all very painful because there is so much in Britain’s Birds to recommend. I described the species accounts and the group introductions, but I haven’t talked at length about all the other great aids towards identification stuffed into each chapter. There is not just one comparative layout of gulls flying; there are plates of small and medium-sized gulls in non-breeding plumage, dark-winged larger gulls, 1st-winter larger gulls, 2nd-year larger gulls, 3rd-year larger gulls, and white-winged gulls. For birds of prey, we have plates of flight silhouettes, Eagles in flight, Kites in flight, Buzzards in flight, Harriers in flight, Accipiters in flight, falcons in flight, plus multiple flight images on each species account. There are drawings comparing the hind claws on pipits, images of hybrid ducks, a table of key identification features of redpoll species, a table on the key features of Chiffchaff races, drawings of tails of Collared Dove, Turtle Dove, and Rufous Turtle Dove, comparisons of the bills of Rook, Carrion Crow, and Raven. It’s almost like the authors went through the book over and over and each time said, “What other cool thing can we squeeze in? Do we have room for Wheatear tail patterns? What about a table on golden plovers?”

There are many books on British birds, but surprisingly few comprehensive guides. The Crossley ID Guide: Britain and Ireland (PUP, 2014) covers 314 birds that reside in or migrate regularly through England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland and a few rare birds. The Collins BTO Guide to British Birds by Paul Sterry & Paul Stancliffe (2015) covers 320 most common birds, and a companion volume, the Collins BTO Guide to Rare British Birds (2015) covers rare birds and vagrants. Probably the closest guide in comprehensiveness to Britain’s Birds is the Collins Bird Guide, 2nd edition by Lars Svensson (HarperCollins, 2008), published in the U.S. as Birds of Europe, 2nd edition (PUP, 2011). The Collins guide covers all of Europe, contains drawings rather than photographs, and is widely considered one of the best field guides in the world. (It’s app is pretty terrific too.)

The two guides make for interesting comparisons–one is full of rich browns and greens and orange-reds and makes your eyes dizzy, the other is cool and elegant, with text on the left and artwork on the right. Each has its strengths. For the time being, I suggest that U.S. birders visiting Great Britain and Ireland stick with Collins. Birders who live in Great Britain or who expect to spend time there, especially beginning and intermediate birders, could gain a lot by purchasing, studying and using Britain’s Birds, despite its drawbacks. The reduced price means you will be getting a lot for your pound. It is a very good identification guide that has the potential, in future editions, of being a great identification guide.

———————————

Britain’s Birds: An Identification Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland

by Rob Hume, Robert Still, Andy Swash, Hugh Harrop & David Tipling

WildGuides, Princeton University Press, summer 2016

ISBN-10: 0691158894; ISBN-13: 978-0691158891

560pages, 6.3 x 1.6 x 8.5 inches

Flexibound edition – $35 (discounted by publisher to $21!); Great Britain – £19.95

Apple iBook – $24.99, available for iPhone, iPad, iPod touch, and Mac; see publisher’s web page for links to all digital editions: http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10715.html#evendors

Hi Donna, a little late for your review but you might find interesting. Charlie Moores interviewed the authors on the Aug 2 podcast of Talking Naturally. http://www.rarebirdalert.co.uk/v2/content/talking_naturally.aspx?s_id=1041083976

Thanks for the heads up, Bob! Have it bookmarked, will listen in the car tomorrow, interested to hear what they say.