Plagues of Biblical proportions can generally be counted on to provide plenty of zoological variety, from droves of frogs and lice to swarms of flies and locusts. Being for the most part more charming and attractive to most humans than these other critters, birds aren’t generally included among these unwelcome hordes. But there is one bird in history that has been associated – rather unfairly – with times of pestilence and disaster: the waxwing.

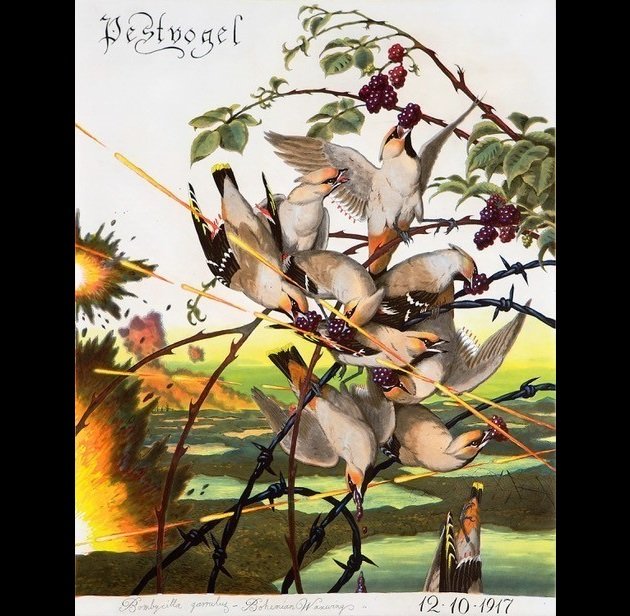

A pair of Pestvogelen: Bohemian Waxwings (Bombycilla garrulus) from Nederlandsche vogelen (“Dutch Birds”) by naturalist and illustrator Cornelius Nozeman (1720-1786) and Christiaan Andreas Sepp (1700-1775) and Jan Christiaan Sepp (1739-1811) of the famous Amsterdam publishing family.

In the Middle Ages, European observers noted that the erratic, southward peregrinations of Bohemian Waxwing (Bombycilla garrulus) flocks often coincided with wintertime outbreaks of plague and cholera. Of course, in our slightly more rational age, we know that these irruptions are driven merely by hunger, as waxwings wander south in search of fruit in the cruelest, coldest winters – just the time of year when humans too are likely to endure significant hardships, as it happens. But because of this coincidence, the poor waxwing came to be known as a bad luck omen of famine, disease, and hardships in general: an old folk name for the bird in Dutch is Pestvogel (“plague bird”) and the Germans have given it the equally harsh name Unglückvogel (“disaster bird”).

Foreboding superstitions about the waxwing persisted into the twentieth century: an irruption of this species in Great Britain during the winter of 1913-1914 was viewed in hindsight as a harbinger of World War I, which broke out the following summer, as depicted in Pestvogel (2016) by American artist Walton Ford (born 1960).

Plague bird or not, whenever waxwings roamed south, people took note of their diet and often followed suit, perhaps in hopes of acquiring some immunity against the pestilence these flocks were said to carry with them by eating the same foods. In Europe, favorite fare of the waxwing includes berries of the rowan and the hawthorn, which do see limited use in human cuisine and drink in products like teas, conserves, and country wines. But much more widely consumed by humans is another of the waxwing’s preferred treats, the juniper berry (Juniperus spp.).

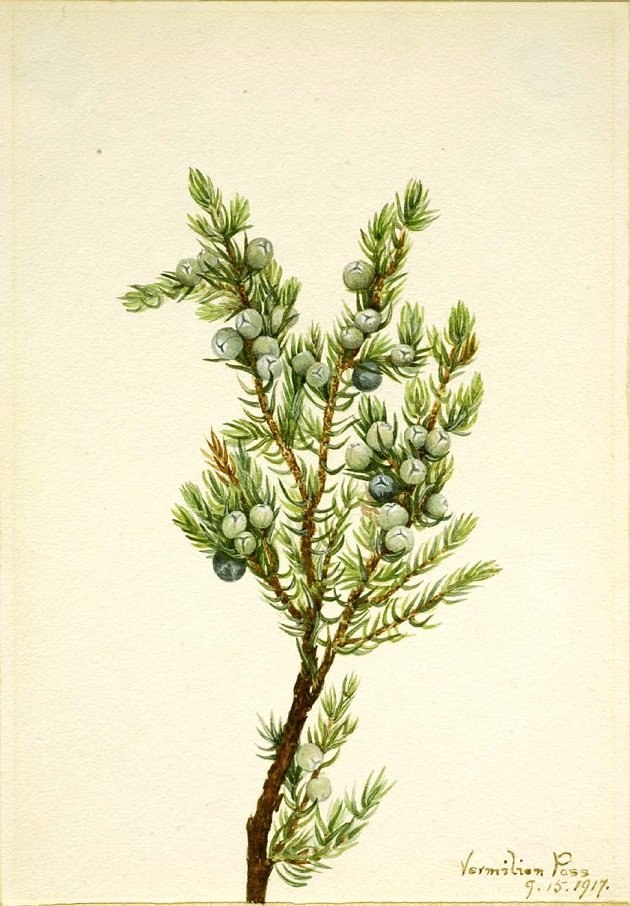

Mountain juniper (Juniperus sibirica) illustrated by Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940), an American artist and naturalist known as the “Audubon of botany”.

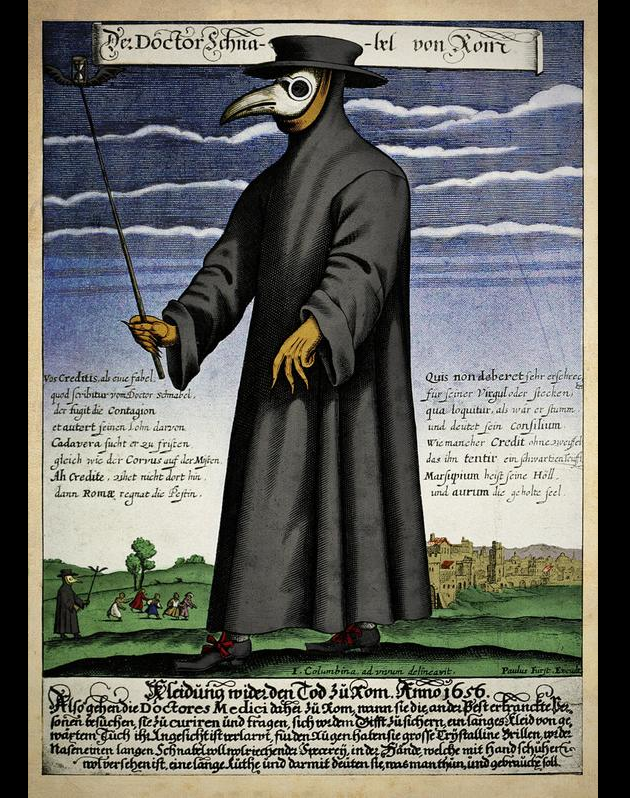

Best known these days as the characteristic seasoning found in gin, the juniper berry has long been prized for both its medicinal and culinary virtues. Perhaps the only spice that comes to our cupboards from a conifer tree, the juniper berry possesses a robust and earthy but ultimately cool and refreshing flavor immediately redolent of the world’s great northern forests. Whether infused, ingested, burned in smudging, or prepared as a salve, the juniper berry is alleged in countless folk medicine traditions to have antiseptic and curative qualities, used to treat all manner of bodily afflictions. This favorite food of the “plague bird” waxwing itself has even been invoked against plague itself: the “beaks” of the strange, bird-inspired masks worn by “plague doctors” from the seventeenth century onward were frequently stuffed with fragrant materials like myrrh, ambergris, and juniper in the belief that these would protect the wearer from putrid miasmas that were said to carry bubonic plague and other pestilence through the air, according to the medical thought of the time.

The invention of the famous plague doctor costume is attributed to Charles de L’Orme, the chief physician to Louis XIII of France, in 1630. The obvious avian features of the mask — here depicted in a circa-1656 copper engraving — earned the plague doctor the nickname “Doctor Beak“, or “Doctor Schnabel” in German.

Given the grim epidemic taking place in our own time, it can seem somewhat insensitive to talk about the enjoyment of food and drink these days, even those that are imbued with allegedly medicinal ingredients like the juniper berry, as is our featured beer this week. But life must go on and our offering today at Birds and Booze – a juniper-flavored farmhouse ale called Waxwing from the Arrowood-Farm Brewery – might serve as a reminder of those dread flocks of “plague bird” waxwings of not so long ago, the purportedly curative juniper berries consumed by both birds and people, and the ease with which people have fallen back on irrational superstition during uncertain times throughout history. By desperately looking in all the wrong places for both blame and a cure amidst fearful waves of pestilence, our ancestors of the recent past were not all that much different than we are, perhaps.

It also doesn’t hurt that juniper berries do taste rather good, both to human and avian palates. Strange as they may seem to our modern tastes, juniper-flavored beers are not without precedent. Undoubtedly many folk brewing traditions in the north of the world have made use of the bright and citrusy flavor of this rich, deep green berry – which isn’t really a berry at all, but a very small, compact evergreen “cone”. The ancient Finnish farmhouse beer known as sahti is a still-living example of this tradition, made by infusing a rye malt beer with juniper berries, which is then filtered through juniper twigs. Juniper was also a common ingredient in gruit, a proprietary blend of bitter herbs used to flavor an ale of the same name in the Middle Ages, before the use of hops in brewing spread across Europe. And of course, juniper has long been imbued in spirits, most famously in modern gin, but also in its direct forebear, a juniper-flavored liquor from the Low Countries called jenever.

A significant Dutch influence still pervades New York’s picturesque Hudson Valley where the Arrowood Farm-Brewery is found, so it’s fitting that the beloved juniper berry — a circumboreal crop early colonists from Holland must have been delighted to find on both sides of the Atlantic — is used to such great effect in this beer. The cool, clear, and unmistakable scents of this “berry” waft over this copper-hued beer with a delicate, sudsy head: fresh, green, and woodsy, but with aromatic, floral notes of magnolia blossoms and citrus as well. But this refreshingly dry farmhouse ale is much more than just a gin-flavored beer, thanks to a bright and herbal palate with flavors of ripe, green pear, sweet, bready malt, and a bright, herbal finish to match those bright, resinous notes of juniper.

Good birding and happy drinking — and be well, everyone.

Arrowood Farm-Brewery: Waxwing Juniper Farmhouse Ale

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Leave a Comment