I haven’t yet been birding in Europe but whenever I occasionally skim a field guide about the birds on the other side of the Atlantic, I’m always encouraged to find that I’m already familiar with many species found over there, even though most of my birding experience has been limited to eastern North America. In many cases, our waterfowl, gulls, and shorebirds are the same as those overseas – or only slightly different – and there are many other corresponding species in nearly all the shared families. Other species previously claimed by both sides of the North Atlantic have only been recently according to range, as was the case with Common Snipe (Gallinago gallinago) and Wilson’s Snipe (Gallinago delicata), or Eurasian Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) and its two North American cousins. Of course, the confusing assortment of warblers in Europe is quite different from ours, but this bewilderment is certainly made up for by all the goldcrests, firecrests, tits, and nuthatches that so often conveniently resemble their New World counterparts.

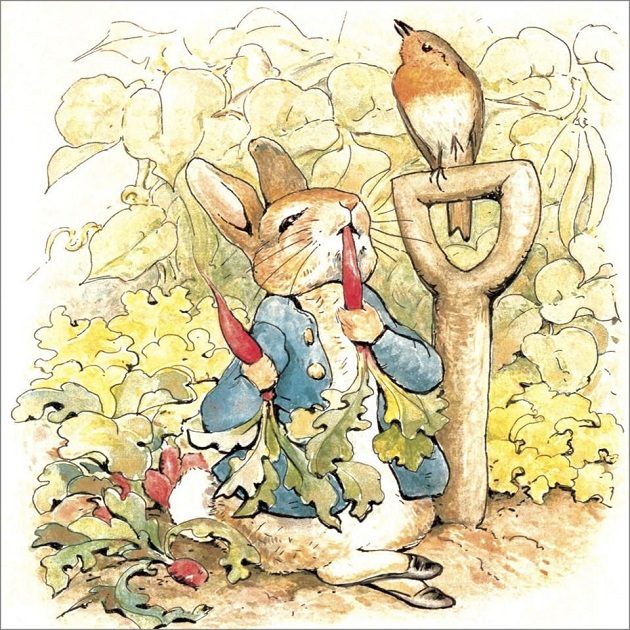

For me, the familiarity of European birds has always been reinforced by the appearance of some of the most iconic species in my steady childhood diet of old fables, fairytales, and folksongs. I remember the talking (Song?) thrush cracking snails on the gray stone in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, the cantankerous Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) Old Brown from the Peter Rabbit tales by Beatrix Potter, and Kehaar, a Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) who was one of the few non-leporine characters in Watership Down by Richard Adams. Besides these, a seemingly endless bestiary of European birds populated the nursery rhymes, children’s books, and lullabies of my childhood, including thieving magpies, baby-delivering storks, ascending larks (or is that the other way around?), cuckoos that really sound like clocks, hawfinches, bullfinches, and chaffinches, blackbirds (without red wings and also in pies), red wings (that aren’t blackbirds), cranes, nightingales, linnets, jackdaws, rooks and so on – even the “robin redbreast” of William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”. Alright, I wasn’t reading Blake as a child, but I do remember the colorful European Robin (Erithacus rubecula) showing up in plenty of fairytale illustrations and Christmas cards.

A Eurasian Robin (Erithacus rubecula) looks on as a presumed European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) enjoys an ill-gotten snack in this illustration by English writer and illustrator Beatrix Potter.

But in all of this, one European bird somehow escaped my notice – and it is perhaps the most unusual and distinctive of them all: the Eurasian Hoopoe (Upupa epops). In fact, I can remember precisely when I became aware of the existence of this odd-looking bird. I was well out of childhood by the time I first saw a depiction of one, rendered in exquisite Meissen porcelain in a pair of eighteenth-century painted figurines at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. At the time, I had just begun birding seriously and I remember questioning whether this peculiar bird with its outlandish crest was even an actual species, rather than some birdlike being of myth and legend like the phoenix or gryphon. And was that silly word really the name of this strange creature? Hoopoe? It all seemed too fantastical to be true.

A pair of hoopoe (Wiedenhoppe) porcelain figurines produced in the early eighteenth century by the Meissen Manufactury from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

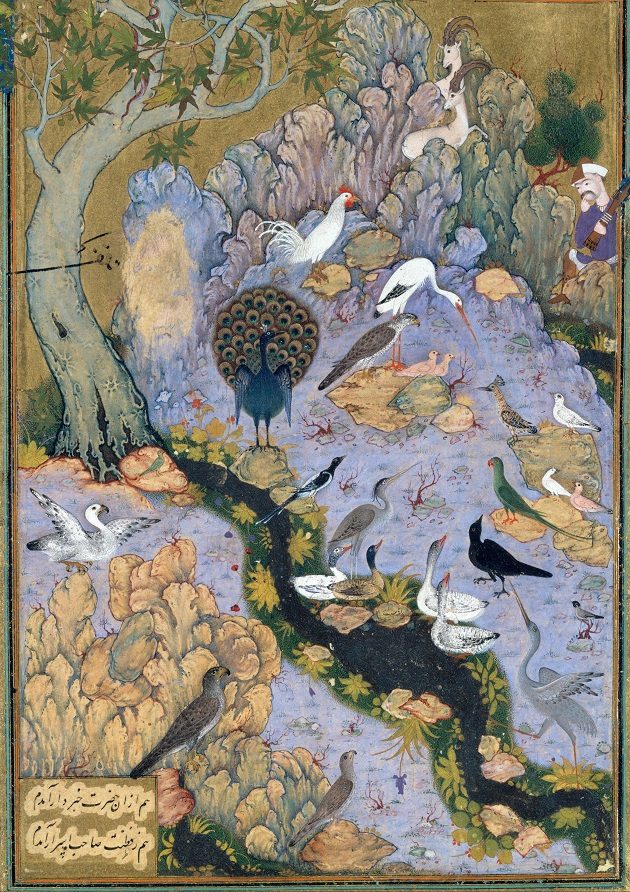

Of course, hoopoes do exist, though I’ve yet to see a real one myself. It’s one of the most beloved birds in many cultures across its wide range, appearing in ancient Egyptian art, the Torah and the Quran (in the former, the Book of Leviticus describes it as an unclean bird that should not be eaten), and in Persian poetry in Mantiq al tayr (The Conference of the Birds) by the medieval Sufi poet Farid al-Din `Attar . In European folklore, the hoopoe has been associated with everything from thievery to war, death, and the underworld, probably on account of its long and sinister bill, which looks like it means serious business. It even appears in the Brothers Grimm fairytale “The Hoopoe and the Bittern” – though that’s one I don’t ever remember reading as a child.

All the other birds gather around the hoopoe in this manuscript illumination from a circa 1600 Persian edition of Mantiq al-tair (The Conference of the Birds) by the medieval Sufi poet Farid al-Din `Attar.

We also have a hoopoe gracing the label of this week’s wine, the 2017 Vinho Verde “Bicudo” from the Quintas das Arcas vineyards in northern Portugal. According to the winemakers there, hoopoes (a summertime breeder in Spain) are commonly encountered along the paths through the vineyard. The name bicudo means “big beak” or “long beak” and isn’t one of the official names in Portuguese – Wikipedia lists boubela, poupão, poupa-pão, and poupinha – so perhaps it’s only a nickname given by the winemakers. Interestingly, the Portuguese name bicudo is also applied to an entirely unrelated Brazilian species, the Great-billed Seed Finch (Oryzoborus maximiliani).

Vinho Verde is both a style of wine and a demarcated denominação de origem controlada (DOC) that dictates its production in what was historically the Minho province in the far northwest corner of Portugal (it now comprises the districts of Braga and Viana do Castelo). In Portuguese, the name vinho verde literally means “green wine”, a reference not to its color but to the relative youth in which these wines are sold and enjoyed. Vinho verde wines are traditionally bottled young and retain a slight residual carbonation leftover from the fermentation. They’re not fizzy enough to qualify as true sparkling wines, but there are enough bubbles to provide an invigorating snap.

A pair of Eurasian Hoopoes (Upupa epops) illustrated in The Birds of Europe (1837) by English ornithologist and artist John Gould.

Vinho verde is sometimes made as a red wine, but the most common incarnation of this style is a light, spritzy white wine, slightly soured from the malolactic fermentation. Once an obscure specialty of northern Portugal, vinho verde has become increasingly popular and easier to find abroad. With its appetizing tartness, the style makes a perfectly refreshing white wine for summer. Better still, these wines lack the heftier price tags commanded by long aging – or the name recognition – of many other European wines.

Vinho verde wines are said to be at their best when young so I sampled this 2017 Bicudo as soon as I picked it up a few months ago at the beginning of the summer, by which point it was at least a year-and-a-half old (I’ve seen the 2017 vintage for sale in a few shops this year, but not the more recent 2018 vintage). Despite having reached its first birthday and beyond, the wine retained a lively fizz. Bicudo exhibits a distinct green apple aroma with a tropical hint of mango and lemon. The delicate but crisp palate is citrusy and tart, with a streak of minerality and touch of fennel in the light, spritzy finish. While summer in the Northern Hemisphere is officially ending for good in just a few days with the autumnal equinox, we have a few days left to enjoy the wine of the season – or to look forward to next year.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Quintas das Arcas: Vinho Verde “Bicudo” (2017)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

Support the most bio-diverse landscape in Europe: the cork oak forest by drinking wine with a cork. That’s all you need to do.