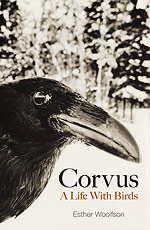

Living in a house with uncaged birds is not for everyone and that goes double for those brave enough to live with corvids. Usually ranked up there as among the smartest of birds, corvids, which include jays, crows, magpies, and ravens, are fascinating creatures that have been mythologized, persecuted, deified, and hunted throughout human history. Esther Woolfson, the author of Corvus: A Life With Birds, was fortunate (or crazy) enough to share her home with both a Rook named Chicken, a Magpie named Spike, and numerous other birds. She captures much of what is wonderful about corvids, and expresses her respect and admiration for the birds with strong and clear prose.

to live with corvids. Usually ranked up there as among the smartest of birds, corvids, which include jays, crows, magpies, and ravens, are fascinating creatures that have been mythologized, persecuted, deified, and hunted throughout human history. Esther Woolfson, the author of Corvus: A Life With Birds, was fortunate (or crazy) enough to share her home with both a Rook named Chicken, a Magpie named Spike, and numerous other birds. She captures much of what is wonderful about corvids, and expresses her respect and admiration for the birds with strong and clear prose.

Some of Corvus reads like a memoir of living with birds and, to me, those are the best parts of the book. Especially appreciated by this reviewer are the minute details of living with corvids, details that Woolfson carefully describes. Behavior like caching food, attempted nesting, responding to outdoor birds, reacting to different music and more give the reader a window into what it must be like to live with a corvid. Where else could one learn that

Not only rooks but even birds with reprobate reputations like magpies could shame humanity by their exquisite attention to manners, effusive displays of gratitude. Nothing, we discovered, is gracious like a corvid. Nothing displays such old-world, mannerly attention to others, such elaborate politisse, such greetings and such partings.

With that kind of description who wouldn’t want a rook as a housemate? Well, living with corvids isn’t all manners and elaborate greetings…

How would you like to find rotting goat cheese hidden under your rugs? Or a rook building a nest under your dining room chair? Or regularly cleaning up bird poop? Living with corvids is certainly not for everyone, but Woolfson seems to think that the sacrifices are worth the effort and inconveniences. She connects with the birds, and at the death of one of them (I won’t be a spoiler) she reacts emotionally:

I wept the night he died. Sitting in bed, filled with the utter loss of his person, I felt diminished, bereft. I talked about him, but not very much, in the main to members of the family, who felt the same, but few others.

It is unusual, to say the least, to find in a book about birds with as much research and careful description as this one to discover the author referring to the loss of a bird’s “person” but Woolfson manages to find a way to express her emotional attachment to the feathered members of her family without going down the dangerous path of overly anthropomorphizing.

Woolfson grapples with the topic of anthropomorphism, not wanting to idealize nor diminish the birds with which she lives. She successfully steers a course between the Scylla and Charybdis of studying birds and nature in general, the behaviorists and the ethnologists. The former she describes as accepting “only what can be reproduced when it comes to animal behaviour” and the latter as willing “to allow what is to behaviourists the unthinkable: conclusions drawn from anecdote, from personal observation, from what just seems to be so.”

To get to this middle ground Woolfson quotes extensively from the ornithological canon, from Pliny to Bernd Heinrich, backing up the nuggets she finds buried like corvid caches with personal observations of Spike and Chicken and the other birds in her menagerie-like home. She also finds precedent for her approach in the concept of ‘critical anthropomorphism’ which she describes as “a concept that encompasses a wide range of critical approaches, physiological, sensory, and ecological.” I must admit that when I first heard of this book I was worried that it would be a saccharine story, not a serious study, but my worries were completely unfounded.

In fact, at times she digresses deeply off-topic in a way that I feel actually detract from the book. The chapter on the evolution of birds is entirely superfluous, though I did enjoy the shots Woolfson takes at creationists. Ditto for the chapter “Of Flight and Feathers” which, in the description of how wings work, drags on interminably. Perhaps others will find these chapters interesting and educational but to me they were a drag.

Though I feel that some chunks of the book could have been removed without diminishing the value of the book I still greatly enjoyed Corvus: A Life with Birds. Those who are as fascinated as I am by the intelligence and dignity (too anthropomorphic?) of corvids will find this book worth buying and reading. Not many people have what it takes to live among corvids and write about them in a way that is both entertaining and educational but Woolfson manages it.

Corvus: A Life WIth Birds is published by Granta Books and is available as a 288 page hardcover.

my favorite corvid, the Common Raven (Corvus corax)

Looks like a fascinating book, Corey. I’ve added it to my WishList. Thank you!

“How would you like to find rotting goat cheese hidden under your rugs? Or a rook building a nest under your dining room chair? Or regularly cleaning up bird poop? Living with corvids is certainly not for everyone, but Woolfson seems to think that the sacrifices are worth the effort and inconveniences.”

———————————————————————–

I say the same thing about my kids on a daily basis.

Hear, hear, Will!

Great review! I’ll have to keep this one in mind, although it’s not going to be published in the US for another 7 months.

@Liza Lee: I think you will enjoy it.

@Will and Mike: And I thought my cats were bad…

@Grant: It is available on Amazon now, but it wouldn’t be shipped for 2-4 weeks. Maybe they are selling the British version?

that sounds like a book i’ll have to get. I share my house with a crow. He comes to my shop every day, where I groom dogs, spends most of his time standing in front of his mirror on the floor, and stashing whatever treat I may give him. He loves to get a shower in the grooming tub, and then a blowdry in one of the drying crates. Thanks for the review!

I only found “Corvids: ALWB” after having very similar experiences with the magpies that have adopted my daughter and grandson, (one has even said “Hello”), and also given us worms, snails and moths after we’ve given them scraps.

I’d found these birds so unsual (even to those magpie friends I’d made when I was young) that I had to write about them here and here… which is why I noticed Corvids:ALWB in my local bookshop and purchased it.

I absolutely adored this book. It was a favorite book last year, and one of my favorites period. A brief review I’d written on Living Social reads:

I finished this book yesterday, and am keenly missing its companionship. It is sweet, thoughtful, mind-expanding, and has made me rethink what it means to be human, to experience life and emotion, have an inner life, and live on this planet. Thank you Esther Woolfson, I loved your book.

I still miss the companionship of this gem.