With only a few more days left, 2017 was coming to a close. Birdwise, it turned out to be a good one and my year list was almost 400 species long, which made me happy… almost. I needed 4 more birds to round it up to 400, and as I said, I had only a few more days left. At home, I may find a new bird, perhaps two, but four? The solution? The Kerkini Lake. This will be the first time I find myself in Greece in winter.

Last evening, Nikos Gallios, the owner and manager of Limneo 3Bs (bed, breakfast & birding) in Chrisochorafa Village asked me what my targets are? Lesser White-fronted Goose and Greater Spotted Eagle came to mind, but what else? Nikos said: “I may have about an hour before breakfast and can take you to see the geese.”

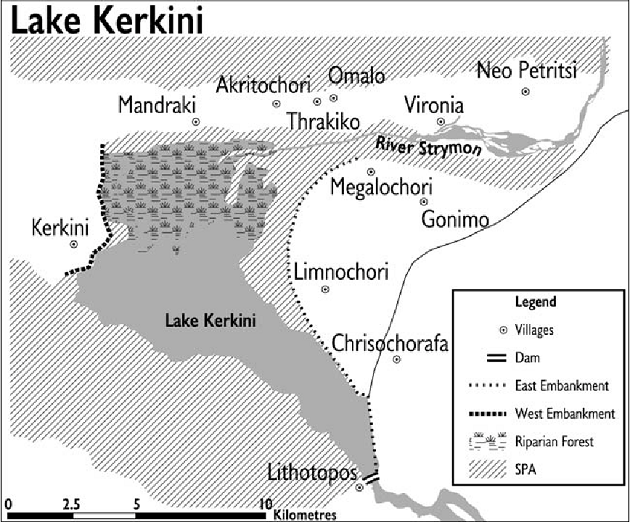

On the morning of December 30th, we were heading north along the eastern embankment through a flat landscape enveloped in a blanket of thick mist. Two kilometre above us, Mount Belles was snow-capped and some two-thirds up the slopes, the thin white cloud sliced up the mountain like a razor in Buñuel’s “An Andalusian Dog”.

Kostas Papadopoulos observing Lesser White-fronted Geese at Kerkini

Kostas Papadopoulos observing Lesser White-fronted Geese at Kerkini

The water level was very low, exposing the large mudbar dotted with waterfowl in the distance. Stopping here and there to scope the mudbar…

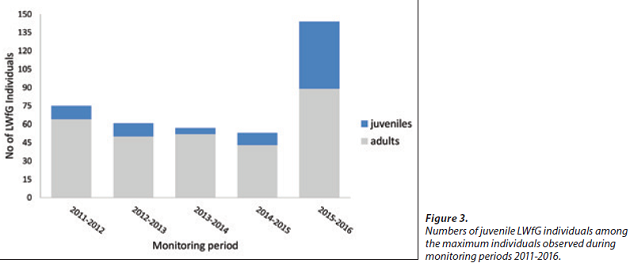

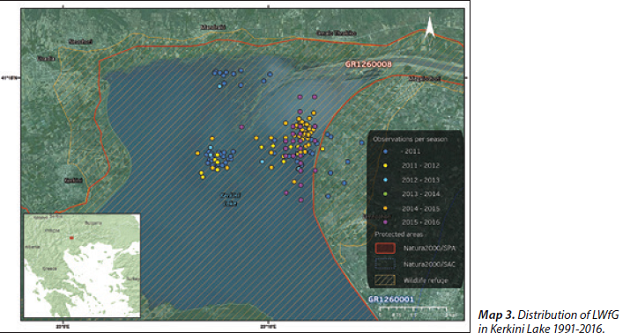

The Lesser White-fronted Goose is one of the most threatened waterfowl species of the Western Palearctic (classified as Critically Endangered in Europe), with illegal killing being the most important threat globally. During the last decade, the numbers in Greece were “mostly stable”, fluctuating from 35 up to 75 birds – representing the total European Fennoscandian population. The winter of 2015-16 was “exceptional” with record numbers of 144 LWfG for Greece and 118 for Kerkini alone (55 of them juveniles) (Source: “The Lesser White-fronted Goose in Greece” by Alehandra Demertzi, Christos Angelidis, Danae Portolou, Manolia Vougioukalou, Eleni Makrigianni & Theodoros Naziridis, 2017).

Both: “The Lesser White-fronted Goose in Greece” by Demertzi et al., 2017

Both: “The Lesser White-fronted Goose in Greece” by Demertzi et al., 2017

Seeing a parked 4×4 and a national park biologist Kostas Papadopoulos scoping the flats… What is he looking at? Lesser White-fronted Geese, of course. (How do you find lions in Africa? Watch for parked 4x4s! This was pretty much the same thing.) With one Black Stork near them, some 80 LWfG were foraging in the distance, where the sun was just now clearing the mist. Then 20 more joined them, so I entered 100 in my notebook. I counted them very roughly, but I do have a lot of experience estimating flocks. Kostas was not merely counting them, but counted one by one, checking also their age and if they have colour rings on their legs and came out with 101 LWfG.

Lesser White-fronted Geese at Kerkini, photo by Kostas Papadopoulos

Lesser White-fronted Geese at Kerkini, photo by Kostas Papadopoulos

One done, three more to go. I am scoping Great Cormorants roosting in their colony in the (now dry) flooded forest, there is one… eagle to the right of them. I am right, Kostas confirms, it is a Greater Spotted Eagle. Focused on watching the eagle, I am deaf and blind to anything else, but Kostas warns me of the honking sounds made by Common Cranes, 18 of them in flight, then 7, plus 6 more, 31 cranes in total and my species #399 for 2017!

By now, Nikos’s time is running out, he has a guesthouse to run. Yet, we didn’t get far when a smallish falcon flew over the dyke and landed on a log in the mud. Too short-tailed to be a kestrel, it’s a Merlin and the species #400 in barely more than an hour on my first morning at the Kerkini lake!

Reaching that threshold, birding become less tense. Afterwards I added species #401, a female Red-crested Pochard along the eastern dyke and the last bird observed in 2017 turned out to be one lovely Little Owl, perhaps 15 metres from the Limneo Guesthouse. Next morning, my first bird in the notebook will be the Greater Flamingo (the truth is, I did see Collared Doves and Eurasian Magpies in Chrisochorafa earlier, but knowing I will see them at the dyke, too, I haven’t written those).

The eastern dyke (the northern section of it) is generally the most productive section of the lake and with 52 species (including all of the above) in winter, it didn’t disappoint me. Yet, with low water level and birds pushed further away, it did disappoint my bird-photographer friend. Among the more notable species of this section (Greater Flamingoes and Dalmatian Pelicans were spread all over the lake) I find one Red-breasted Goose, 7 Bewick (Tundra) Swans, one young White-tailed Eagle and 5 different Greater Spotted Eagles – 4 of them in the same morning and two of those right next the dyke, plus one magnificent pale fulvescens form. Add to that picture one more cool beast, the European Wildcat crossing the dyke in front of the car (and it wasn’t the only one, other Limneo guests had their own wildcats, too).

Circling the lake anticlockwise, the northern shore was the least productive, but the western dyke (the northern half of the west shore) with 45 species was very good. Unlike the previous embankment, this one had a smaller, bird-rich mudbar close by and shallows in its northernmost section, followed by deeper water, decreasing the diversity of waterbirds, but the further south one goes, the diversity of songbirds increases. One of the sights to remember here were Greater Flamingoes feeding in deep water, up-ending like swans and splashing the water with bright pink legs like a person learning to swim. This dyke also produced 3 Eurasian Spoonbills, one Greater Spotted Eagle, Eurasian Curlews, Hawfinches, Eurasian Siskins and one Sardinian Warbler. Last but far from least, there was a curious Golden Jackal observing us, then running a dozen metres to stop and observe us again.

Continuing anticlockwise, south of the western dyke comes the Korifoudi flats, an extensive mudbar where some good birds are to be found anytime. Common Snipes (34) and Water Pipits (40) were two birds that stood out for me because I found them here in January 2018, while I missed them during the entire 2017 and they aren’t uncommon – I just missed them. The best species was the Temminck’s Stint, clearly showing its yellow legs, two of them among those Water Pipits.

Further south, heading towards the dam, is a cove from where Nikos Gallios sails out for Dalmatian Pelican photography tours. I was on two of these and I highly recommend them. Winter is the high-season here when it comes to photographing pelicans because their beaks are at their brightest and the most handsome. Light-wise, daybreak and sunset are the best times (it can be a bit chilly in the morning), and Mt. Belles creates a perfect background.

Further south, heading towards the dam, is a cove from where Nikos Gallios sails out for Dalmatian Pelican photography tours. I was on two of these and I highly recommend them. Winter is the high-season here when it comes to photographing pelicans because their beaks are at their brightest and the most handsome. Light-wise, daybreak and sunset are the best times (it can be a bit chilly in the morning), and Mt. Belles creates a perfect background.

Yet, I am not a photographer (I just have a camera, which is not a qualification in itself). So, what to do? Have high hopes and make at best a bunch of very average photos and mostly very inferior ones? Nope. I’ll play with my mobile phone. Photographing birds with mobile phone? Sure, why not.

Yet, I am not a photographer (I just have a camera, which is not a qualification in itself). So, what to do? Have high hopes and make at best a bunch of very average photos and mostly very inferior ones? Nope. I’ll play with my mobile phone. Photographing birds with mobile phone? Sure, why not.

Afterwards, Nikos will receive an email enquiry how far the pelicans are and how much time is needed to reach them. The answer is, these beasts have learned to follow fishermen as they pull in their nets and will be all around the boat, already waiting in the cove when you arrive. One piece of advice: don’t bother with your telephoto lens, bring maximum 100 mm, plus a wide-angle lens. Or your mobile phone, whatever.

Afterwards, Nikos will receive an email enquiry how far the pelicans are and how much time is needed to reach them. The answer is, these beasts have learned to follow fishermen as they pull in their nets and will be all around the boat, already waiting in the cove when you arrive. One piece of advice: don’t bother with your telephoto lens, bring maximum 100 mm, plus a wide-angle lens. Or your mobile phone, whatever.

The last area to visit was the town of Sidirokastro (literally “the iron castle”). Finding my target bird there was easy, but finding the castle on whose buttresses it lives was more complicated. My first attempt ended up in front of some closed gate, but later I asked Nikos how to get there, only to discover olive groves and pine forests that I want to explore more in the future. And the target was a Western Rock Nuthatch (above), a species that lives from the Balkans east to Iran, which cooperatively called for attention from the wall the very moment I got there.

The last area to visit was the town of Sidirokastro (literally “the iron castle”). Finding my target bird there was easy, but finding the castle on whose buttresses it lives was more complicated. My first attempt ended up in front of some closed gate, but later I asked Nikos how to get there, only to discover olive groves and pine forests that I want to explore more in the future. And the target was a Western Rock Nuthatch (above), a species that lives from the Balkans east to Iran, which cooperatively called for attention from the wall the very moment I got there.

Kerkini Factfile

The Kerkini Lake is one of the youngest national parks of Greece, protected only in 2006 and inhabited by 11 amphibian, 27 reptilian, 44 mammal and 312 bird species. The lake lies at 35 m / 115 ft a.s.l. among the 2000 m / 6500 ft high mountains (hence, offers a wide range of habitats), about an hour north of Thessaloniki or three hours south of the Bulgarian capitol, Sofia. Its surface area fluctuates from 50 km2 / 19 sq mi in August-September to 75 km2 / 29 sq mi in May-June. The maximum length is 17 km / 11 mi (north-south) and the max. width 5 km / 3 mi (east-west).

National park authorities in Kerkini village

I stayed at birder-friendly Limneo Guesthouse in Chrisochorafa

Organised bird-tours are offered by Natural Greece

For additional info, the BirdLife Greece has recently published Birding in Greece

Really nice birds to finish off the year. I would love to see the beasts on that lake!

Indeed. And I’d love to guide you there 🙂

I want in too!

Would be happy to arrange the trip for you and guide you personally (Y)