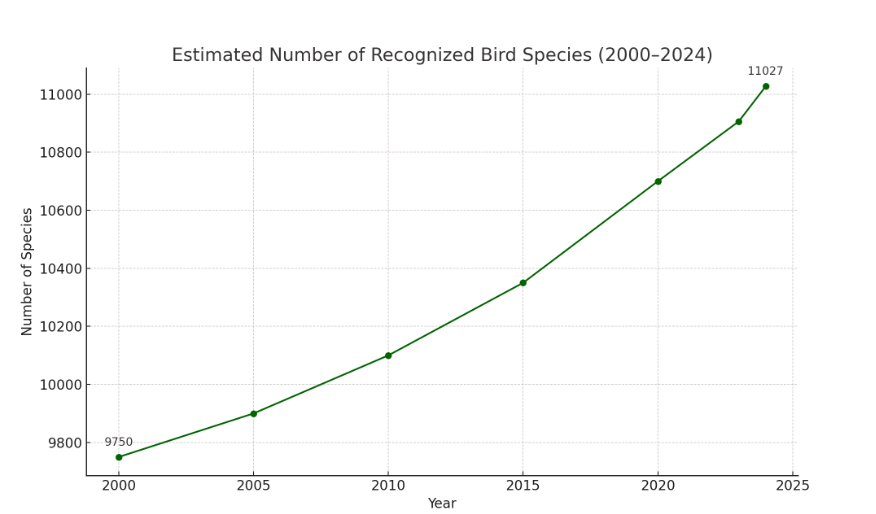

As you can see from the chart, the number of recognized bird species has increased from about 9,750 in 2000 to a bit more than 11,000 in 2024. Why?

Mostly, this is the result of species being split, rather than new species being discovered. Only about 5-10% of “new” species are the result of newly discovered birds, the rest are established species being split.

As ornithologists learn more about known bird species, they sometimes discover substantial differences within an established species. Newer tools and technologies, such as DNA analysis, as well as an added focus on bird behavior, are among the drivers of this process.

For example, in 2023, the Northern Goshawk was split into the Eurasian Goshawk and the American Goshawk, as their DNA shows substantial differences, and their vocalization is also different. Somewhat ironically, this is the reversal of a lumping of the two species about 80 years earlier.

There are also truly new species identified, typically 5 to 10 each year. For example, in 2022, the Meratus White-eye was formally described (as if the world needed more White-eyes). It had probably escaped ornithologists before, as it has only a small range and does not look all that different from some other species of white-eyes. The Inti Tanager is a more interesting example, a species discovery that required a new genus (i.e., it is not strongly related to the established species).

Purely based on the mathematical shape of the curve shown above, there will be about 15,000 bird species by 2100. Of course, most of us will be dead by then.

Sidenote: even though the rise in species makes the name of our website, 10,000 Birds, sound slightly outdated, we have no plans to change it.

You can never have enough white-eyes though!

Duncan! You stole the words right out of my mouth. There could never be enough white-eyes…

Duncan and Peter, you can have the white-eyes, just leave the other species to me.

Just saw two more white-eye species… 🙂

My condolences.