The Cuckoo Cuculus canorus has a bad reputation because of its habit of laying its eggs on the nests of other birds, who then raise their young. But in south-west Europe there is a bird that kicks out the sitting tenants and takes over the nest altogether. The White-rumped Swift Apus caffer, a tropical African breeding species, was only discovered breeding in Europe in the 1960s. This was in southern Spain, near the town of Zahara de los Atunes in Cádiz Province, on the northern shore of the Strait of Gibraltar. At the time the bird was confused with the Little Swift Apus affinis, a similar species, also with a white rump. The confusion was understandable. Little Swifts breed in Tangier, just a few kilometres on the other side of the Strait so it would have been logical to expect these to have made the short sea crossing into Europe.

The White-rumped Swift, on the other hand, had a sub-Saharan distribution so nobody suspected it to have made the jump across the Sahara. If its arrival was shrouded and mysterious, its nesting behaviour is truly a cloak and dagger affair. White-rumped Swifts arrive in April and seek out Red-rumped Swallows Cecropis daurica. They have also arrived from tropical African wintering grounds and, by that time, are busy repairing old nests. These are mud constructions, easily identifiable by a long entrance tunnel, that are placed on the roofs of culverts, under bridges and similar structures. The swifts arrive, seek the swallows out, find their nests and evict the tenants! They then settle in their newly acquired home, lay their eggs and raise their brood. How can you tell if a Red-rumped Swallow’s nest has been taken over? Easy. The swifts line the entrance with white feathers – it is the clear sign that this is now property of White-rumped Swifts and it may also be a way of showing a potential mate that this bit of real estate has an owner.

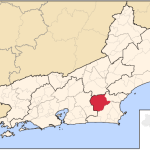

The population of White-rumped Swifts has expanded slowly, in numbers and geography, some now breeding as far north as Extremadura in central Spain, but the stronghold remains the Strait of Gibraltar. Recent estimates suggest that the population may be of the order of 200 pairs. That’s the entire European population, tucked away in south-western Iberia.

What triggered this expansion from Africa? I have a hunch that it was the Red-rumped Swallows themselves. Howard Irby, writing at the end of the 19th Century said that the Red-rumped Swallow had been recorded from Malaga and Valencia. In other words, it was a rare bird. Nowadays, Red-rumped Swallows are abundant and widespread breeding birds so there must have been an arrival and expansion during the 20th Century. The swifts would have followed. They were first detected in the 1960s but who knows how long they had been there before that?

What of the Little Swift? Curiously, they also breed in Iberia today. They were first detected in Malaga in 1981 and in the Strait of Gibraltar area in 1983 and are slowly spreading northwards. The population is small, perhaps no more than 200 or so pairs, and the main concentration is, again, in Cadiz Province, SW Spain. They breed in colonies, often close to human habitation.

I’m lucky to live close to these two gems and in a part of Europe that boasts no fewer than five breeding species of swift!

You’re in a good spot in Iberia, Clive. Still need to see this swift in Portugal – it arrives here in the midst of summer. I never feel like going out into the hot interior for a bird I have seen so many times elsewhere. I guess I am not a very good twitcher. Have seen the Little Swift in Portugal (by accident) so maybe I should make an effort and go for the “full house”. By the way, the White-rumped Swift has its own place in the book I mentioned a while back: https://www.10000birds.com/no-rain-in-spain.htm

A number of years ago legendary beat writer here, Redgannet, posted an article titled “Don’t take pictures of swifts.”

https://www.10000birds.com/dont-take-pictures-of-swifts.htm

You seem to have definitively invalidated his previous post. 😉 Bravo, Clive!

In 1968, as a teenage birdwatcher, I stayed with F.G.H. (Geoffrey) Allen, the Englishman who first discovered white-rumped swifts nesting in Andalucia. He was a skilled ornithologist, but had understandably mistaken the white-rumped swift for a little swift, as Clive mentions. His classic photograph of the nesting swift (he was a fine photographer) was published in The Times newspaper at the time.

Geoffrey lived with his wife Betty in Los Barrios, close to Gibraltar.

Betty was a great botanist who discovered the fern Psilotum nudum close to Los Barrios – a Tertiary relic found nowhere else in Europe

well, new kit helps!