Amy Evrard has a PhD in social anthropology from Harvard University and loves to write about human relationships with nature. But that makes her sound awfully stuffy. As a clumsy person, she enjoys the experience of literally stumbling through nature, learning as she goes, experiencing the magic of finding something interesting. Although she has loved birds all her life, she is relatively new to birding and enjoys everything about it except the bug spray. She teaches anthropology at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, USA, and lives in Maryland with her husband and not nearly enough pets. This is Amy’s first contribution to 10,000 Birds.

I’ve hit an all-time low. With apologies to my mother, I am using sex to lure readers to this post on 10,000 Birds. Not only sex but the word “voyeurs,” which calls to mind those questionable people who watch others have sex. If we see that the number of views and comments reaches an all-time high on the site, we’ll know something about you readers!

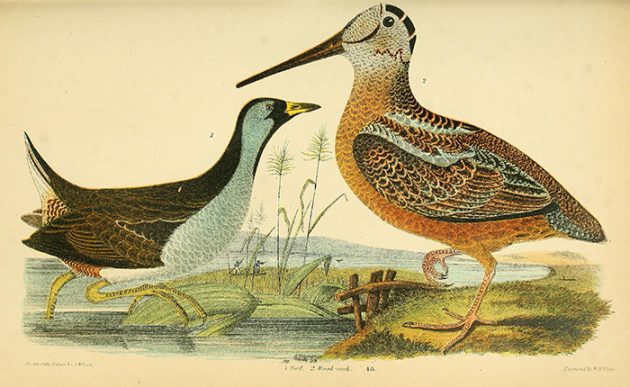

A few weeks ago I joined a group of bird lovers to go out to a little clearing in the woods of West Virginia and watch the skydance of the American Woodcock. For a couple of weeks or so, anytime from January to May, male woodcocks will come out to the field from dusk to dawn, make a strange little peent noise, do a funny little dance by moving forward and backward, and hope to convince a female woodcock to approach for a quick mating. After dancing a few times, the male will fly up and do a spiral formation high in the sky, before returning to the ground, wings whistling, to dance once more. If the courtship displays begin just a little bit before dusk or keep going just a little bit after dawn, there’s a chance that bird sex voyeurs can get a glimpse into their world through the dim light.

This is enough of a thrill that eleven of us came out on a chilly evening. Some brought lawn chairs for comfortable, front-row seating. Some brought binoculars or scopes. Some brought flashlights. We were ultimately disappointed that we had waited too late in the season. While we got to hear a couple of males and watch them fly up in the air, there appeared to be no more females in the mood to mate, so we only saw a truncated version of the ritual carried out by a couple of lonely, frustrated males. Still, I couldn’t help feeling embarrassed for the woodcocks and embarrassed for myself, wondering if we were all a bunch of sex-obsessed weirdos.

Strange reaction, huh? We’re talking about birds here. They mate out in the open, for all the world to see, and of course they don’t care one way or the other if a human is watching through binoculars. But we in the United States have some rather repressed notions about sex, which have made their way into our understandings of the natural world. Think back to Victorian mores of sexuality prevalent among the upper classes in Great Britain and North America, which were so repressive and repressed that many Victorians felt that books by male and female authors should not be shelved next to each other in libraries. These mores informed the work of Charles Darwin and other naturalists who insisted (inaccurately, it turns out) that female animals are generally elusive and monogamous when it comes to sex. America’s Puritans scrapped the common English word “cock” to describe the male chicken and popularized “rooster” as its replacement. Never mind that this made little sense, given that both male and female chickens roost. It was a necessary move to save well-bred young ladies from having to speak or hear the word “cock”, which had become a slang word for “penis”. All these generations later, I may well be imposing this history of societal mores on the innocent act of bird mating by the haplessly named American Woodcock.

I can’t help wondering if my fellow birders have the same thoughts, or if American birders have these thoughts and, say, Brazilian or French birders do not. I think it would make a fascinating research study. In the actual moment of these realizations, however, my way of dealing with such confusing thoughts was to make a joke, one with sexual overtones to match the confusion. As we were packing up to leave the clearing, one of my fellow birders said, “Well, we’ll try again next year.” I quipped, in my best dirty-old-woman voice, “Yep, now that I have a taste for woodcock, I’ll definitely be back!” No one laughed. I’ll leave you to analyze that one for yourself.

Leave a Comment