When was the last time you birded in the oldest forest preserve in the western hemisphere? If you have never been to the Tobago Main Ridge Forest Reserve on the island paradise that is Tobago, the answer is never. Since 1776 it has been protected land and the biodiversity there speaks volumes to what nearly 250 years of conservation can do. But I think that UNESCO explains things better than I can:

The Tobago Main Ridge Forest Reserve is on record as the oldest legally protected forest reserve geared specifically towards a conservation purpose. It was established on April 13th, 1776 by an ordinance which states in part, that the reserve is “for the purpose of attracting frequent showers of rain upon which the fertility of lands in these climates doth entirely depend.” The passage of the ordinance is attributed to Soame Jenyns, a member of the British parliament whose main responsibilities were trade and plantation. He was influenced by the ideas of the English scientist Stephen Hales who was able to show the correlation between trees and rainfall. It took Jenyns eleven years to convince the parliament that this was indeed a valid endeavour. Scientific American has commented “…that the protection of Tobago’s forest was the first act in the modern environmental movement”. This can be considered a landmark in the history of conservation and preservation of the environment. The living testimony is the survival of the Forest Reserve itself.

Thank you, Soame Jenyns!

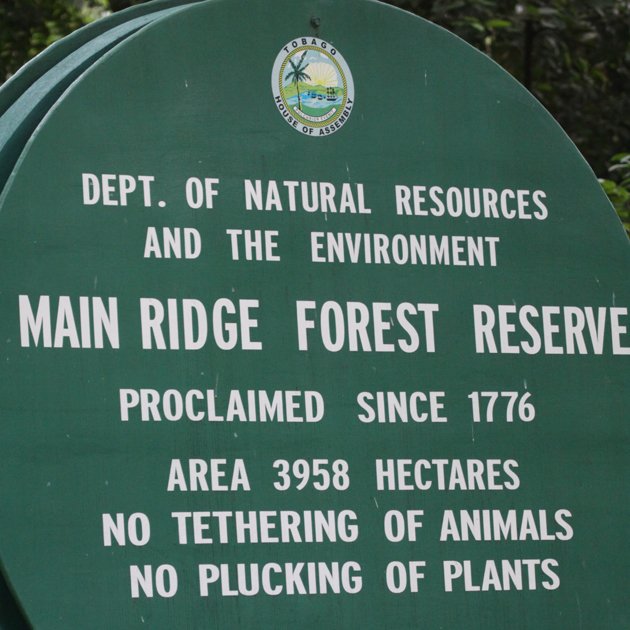

the entrance sign at the reserve

My visit to the Main Ridge Forest Reserve took place on 16 July 2013. We didn’t get to the Gilpin Trace, which is one of the most popular access points to the forest, until 9 AM, where we were greeted by Newton George, who was to be our guide for our visit. He is gregarious, knowledgeable, and eager to get you on the birds, which was a bit difficult for most of the people in my group, which consisted of six people, considering I was the only birder.

Newton George giving a talk about the history of the reserve at the beginning of our walk

Before we even started down the trail he had pointed out a trio of Broad-winged Hawks circling overhead. They had been calling, but for some reason the familiar sound didn’t register for me. Fortunately, this was not an exception, but a rule, as Newton proved himself quite adept at hearing, seeing, or maybe even just sensing nearby birds and making sure that he at least gave us the opportunity to see them. (You really couldn’t blame him for the fact that not everyone had binoculars, especially considering he brought two pairs for people to use, nor for the fact that some folks in our group didn’t really want a good look at, say, a Fuscous Flycatcher.)

And while we didn’t see or hear a ton of species (29 by my tally) there were some pretty darn good birds in that small total. The fact is that rainforest birding is hard and if a mixed flock doesn’t happen along it is unlikely that you will see lots of birds. Even without a mixed flock we managed to hear Plain Antvireo and Olivaceous Woodcreeper (with a poor glimpse gathered of the latter) and spot a Stripe-breasted Spinetail, all really good birds that would pretty much only interest birders. More interesting to the non-birders were the Rufous-tailed Jacamar and Trinidad Motmots that we saw, though they did stay rather distant. And everyone was very pleased by one of the stunners, a Tobago specialty, the Blue-backed Manakin. We saw several feeding on strangler fig.

Blue-backed Manakin Chiroxiphia pareola (male above, female below)

Newton George also pointed out a variety of flora, to say nothing of his uncanny ability to spot Trapdoor Spider holes. We only walked out about half-a-mile (to the first waterfall) and back and I imagine that if we had started earlier we would have seen quite a few more interesting birds, but non-birders don’t like getting up early and even our 9 AM arrival at the Gilpin Trace had caused some grumbles.

In addition to the species already mentioned I also particularly liked the Rufous-breasted Wren, of which we saw several, one of which is at the top of this post, Yellow-legged Thrush, of which we saw a pair, White-necked Thrush, which behaved exactly as the field guide warned by hopping down the trail, and Scrub Greenlet, which we observed as it fed a fledgling.

But the best sighting of our entire walk was of this female White-tailed Sabrewing, a Near Threatened species according to BirdLife International, which is found only in the Main Ridge Forest on Tobago and in northeastern Venezuela. She was very cooperative.

female White-tailed Sabrewing Campylopterus ensipennis

The Gilpin Trace is a great place to go birding. It is also a great place to bring a family, even with relatively small children, to teach them about the rainforest. The hike isn’t hard at all and even though there is a guy who rents out rubber boots at the entrance they were not at all necessary on the day I was there – my sneakers were more than adequate. I can’t speak highly enough of Newton George as a guide. Our group with its varied interests was kept engaged and entertained by his personality and his obvious and abiding respect for and knowledge of the reserve.

…

My visit to Trinidad and Tobago was sponsored by the Trinidad and Tobago Tourism Development Company but the views expressed in the blog posts regarding the trip are my own. For more information about visiting Trinidad and Tobago a good place to start is the official tourism website.

…

Is it my European genes that make me enjoy the wren more than the manakin?

@Jochen – Yes.

I second Felonious. I just wish I had gotten a clearer shot of what is a pretty darn cool wren which also has a great song.