I’ve just returned from a trip to Israel and I feel like I’ve run 300 miles in a week…in the blazing sun…uphill…with no water…and carrying a one hundred pound sandbag. In reality I’ve returned from filming the second Champions of the Flyway Bird Race. And I had it easy. Compared to the 135 participants of this, arguably the most grueling 24-hour birding competition in the world.

Teams from the Champions of the Flyway gather to view the raptor migration in the mountains close to Eilat.

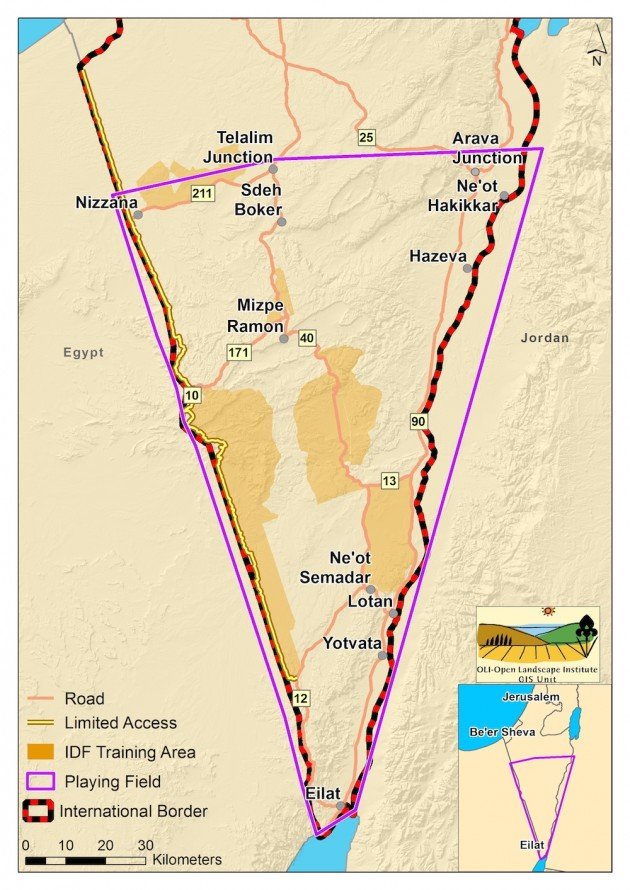

The 31 teams, 15 of them international and 16 local, set out as the clock struck midnight on March 24th, 2015 to scour the southern part of Israel for as many bird species as possible. Although highly competitive, what makes the Champions of the Flyway different from other bird races is that contestants share their sightings as they go – enabling others race teams to locate any highly sought after birds. Additionally, with the advent of What’s App and Twitter, the teams tweeted their sightings in real time so that anyone, anywhere in the world could follow the race live on Twitter, whilst the participants raced from one What’s App sighting to another.

The playing field for the race was limited to southern Israel

A male Crowned Sandgrouse – just one of the 235 species seen during the race. Jonathan Meyrav

The competition takes place every year during the height of spring migration as millions of birds funnel through Israel on their bi-annual migration. During this year’s competition, each team raised money for – and awareness of – the illegal trapping of migratory birds in Cyprus, a fitting cause for a race that celebrates the miracle of migration. Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean and is a crucial stop-over for migrating birds. Since 1974 it has been illegal to harvest birds there with mist-nets and limesticks. However, this law has had little effect on curbing the illegal trapping. Not surprising when one considers that ambelopoulia (a fancy name for a plate of songbirds) sells for €40. The competition raised over $50,000 for this very important cause.

Temminck’s Lark was one of the more difficult lark species spotted by many of the teams Jonathan Meyrav

Trumpeter Finches are highly sought-after birds Jonathan Meyrav

Trumpeter Finches are highly sought-after birds Jonathan Meyrav

Whilst following the race, I was most impressed by two things. Firstly, this is a competition that prides itself on diversity. It was refreshing to witness the enthusiastic participation of women and children, although thankfully I didn’t see any kids behind the wheels of any of the vehicles! It was also good to witness a mixed Palestinian/Israeli team, a testament to the fact that birding has the potential to bridge cultural and political divides.

Secondly, the sharing aspect was phenomenal. At first, I surmised that the sharing of sightings would reduce the competitive nature of the race. But, if anything, it enhanced it. In some instances, teams had to choose if it was worthwhile to chase down a single species. A case in point was the discovery of a Black Bush-robin at the Yotvata sewage works by the Next Generation Birders from the UK. This bird is a rare visitor to Israel and many of the participants really wanted a look at this charismatic species. But some teams raced to get a glimpse, only to wait in vain for many frustrating minutes as the bird hid determinately in a bush, thereby losing time to search for more birds. For the teams that saw it, the sighting was well worth the effort.

The discovery of a Black Bush-robin had several teams re-adjusting their itineraries…

Two rare birds that were not on the official race bird-list due to the sensitivity of disturbance by multiple teams were the newly described Desert Tawny Owl and the Nubian Nightjar (a bird that has been reduced to approximately a dozen pairs in Israel). Instead, the race organizers organized a special trip before the start of the race to see both of these incredible birds and the teams that decided to participate were not disappointed. The Desert Tawny Owl in particular is a fascinating story. A case of mistaken identity, this rare and secretive species, was only officially described to science in the last year.

The mistake has its origins in 1878, when ornithologists Henry Tristram and Allan Hume both collected specimens of what was then described as Hume’s owl. Tristram believed that his specimen was the same bird and nobody thought any different until over a century later when researchers established that the newly-described species was about 10 percent different from that of the Hume’s owl, a surprisingly large genetic variation. Named for the legendary Israeli ornithologist, Hadoram Shirihai, the new species, strix hadorami, finally gets its due. We managed to film this fascinating bird for the first time as two birds called to each other in a remote canyon in the Judean Desert.

Rare footage of Desert Tawny Owl

But back to the race…The vast majority of the teams decided to speed up north at the kick-off and begin to work their way south to Eilat. One exception was the American Dippers team who, when asked mid-race why they decided to do things backwards, replied somewhat prophetically that they had it right and that everyone else was doing this race the wrong way round.

In a frantic and dramatic race that included teams being chased off the crucial Meishar Plains by security personnel and one team getting their vehicle stuck in the sand, participants raced from one key birding site to another, hoping to win the coveted title of Champion of the Flyway. At 7.00 pm the finish line was opened in Eilat and teams slowly began to trickle in and hand in their checklists, with some teams waiting until the final minutes before the race officially closed at midnight.

As for the results of the race, it sure was a close one. The Cape May Bird Observatory American Dippers took top honors out of the international teams with 168 species, a mere one bird ahead of the Arctic Redpolls from Finland with 167 birds. The Reservoir Birds from Spain and the Finnish team, Northern Lights, shared 3rd place with 163 species.

The winners of the Israeli competition were the Jerusalem Bird Observatory Orioles with a mammoth total of 179 species, a new Champions of the Flyway record. They were closely followed by the Pied Bushchats from the Yerucham Center for Creative Ecology with 176 species and the “Terns” from Ma’agan Michael notched up 170 species for third place. In the sharing spirit of the race the ‘Knights of the Flyway’ trophy for the team that enables the most species to be seen by opposing teams was awarded to the Next Generation Birders from the UK. The “Guardians of the Flyway” award for the team that raised the most money for BirdLife Cyprus, was handed to the Birdwatch/Birdguides Roadrunners who raised over $7,500 for this great cause.

And so the second Champions of the Flyway, the Dakar Rally of birding, has come to pass. And while the teams catch up on many hours of lost sleep and get back to their regular lives, they can all be proud of their part in leaving a lasting impression on the birds that pass through Cyprus twice a year.

CHAMPIONS OF THE FLYWAY BY THE NUMBERS

5 Total number of volunteers and coordinators

31 Teams participated in the race

168 Winning total

231 Total number of birds seen by all teams

314 Number of What’s App messages shared during race

52,000 Total amount raised in US$ for conservation

I was fascinated how Whatsapp seemed to be changing the way people do fieldwork when I was in Aftica.