A birding trip is more than arriving to your destination and watching birds. It’s also getting ready for the trip and in a sense, once you buy that plane ticket, when you begin with serious planning, you are on your way! A successful birding trip is a process, one that requires a fair degree of planning and as much studying as you want (or can handle). At times, studious birders may wonder if staring at plates of antbirds is worth it, if attempting to memorize differences in woodcreeper bills and parsing out flycatcher vocalizations will pay off. These are good things to think about, especially if you have a regular life but trust me, fit in the study time and the birding trip is gonna be enhanced!

Once you get to Costa Rica, you’ll already know those birds so well, it will be like meeting distant family members and famous folks for the very first time.Over and over! You may say to yourself, “Ha! That’s a great view of a Great Kiskadee for sure! Hello my well recognized friend. By jove, there’s a Boat-billed Flycatcher! I know that guy! Whoah, and this smaller kiskadee thing must be a Social Flycatcher! Why do I feel this strong desire for an autograph? I better take a picture or maybe a100..”.

A knowledgeable guide will triumphantly proclaim vocalizations that ring through rainforest, “Scarlet-rumped Caciques!” and you will know they are right. Your preparations will also reveal when someone is actually a pseudo birding guide. You’ll know this is the case when the guide focuses a bit too much on Clay-colored Thrushes while misidentifying obvious toucans and ignoring wrens. In brief, you’ll be ready for those birds in Costa Rica, ready to soak them up and have a fantastic trip.

When you study the plates in the field guide and quiz yourself with birding apps for Costa Rica, whether you want to or not, you will also pick out target birds. As much as you try to be neutral about it, thinking that all birds are equal and that you will be happy with whatever you see, favorites are still gonna be there. There might be 300 favorites but they will be fave, hoped for birds nonetheless.

The party pooper is that some of those favorites won’t be seen. After becoming enthralled with birds in books and on apps and looking forward to meeting them in Costa Rica, this can be a tough pill to swallow. However, the truth about birding trips is that one rarely sees every single bird, especially on trips to places with bird lists that surpass 900 species.

With limited time, you just won’t see everything. Some birds will be in regions relegated to the next trip to Costa Rica, some are super rare and easier in other places (hola senor Pheasant Cuckoo), and others are just anti-social pains. There’s a fair chance you won’t even see some birds that seem like they should be seen. Right, say what?! These are the infamous “false rare” bird species of Costa Rica; uncommon birds assumed to be rare because they are so infrequently encountered. The following birds top that nefarious list:

Agami Heron

It’s so easy to say that this wading royalty is a rare heron but that designation really depends on how the word is defined. While this beauty isn’t nearly as numerous as Little Blue Heron or some of the other beak stabbing species, there are more than a few Agamis in Costa Rica. The problem with these fancy birds is that they loathe being seen. Despite that feathered finery, Agamis prefer their own, private fish parties, ones that take place in shaded jungle streams and quiet wetlands.

You could see one, I hope you do but sadly, the bird is far from guaranteed. Experienced bird guides in Cano Negro can up the odds and if you visit the Pacuare Reserve in May, you’ll get mindblown at a breeding colony (!). In general, though, a birder needs to get lucky with this prize. Keep peering into forested lowland streams and wetlands and it might happen.

Tiny Hawk

How tiny is it? Take a male Sharp-shinned Hawk, make it a little bit smaller, tell it to never ever soar, and then stick it in tall rainforest. That one sentance probably sums up why this bird is so hard to see. I wouldn’t say it’s common but it really isn’t rare either. It just hides most of the time, ambushing small birds in plain sight.

Scan tall trees at the edge of rainforest in the early morning and you might get lucky. Don’t overlook that odd looking thrush with the dark cap and blocky head because that funny little bird just might be a Tiny Hawk.

Olive-backed Quail-Dove

Believe it or nor, this bird isn’t actually rare either. It’s just a quail-dove that lives in dense, wet rainforest. All a birder can do is keep birding those places, keep on watching the trail as far ahead as you can see and be ready for movement on the forest floor. Don’t expect to watch it for long but one fine day, one of these quail-doves will appear.

Whiet-chinned and Spot-fronted Swifts

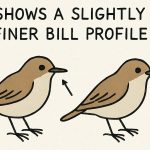

The deal with these birds is that they have the same shape. There could be a subtle difference but if you really want to be honest with your field identification, you really should hear them call or get a good look at the head in good light. Sounds easy enough and it would be if the birds flew low enough to see those markings, and if they called all the time.

They don’t.

When they do, they can be identified but most times they don’t and that’s why so many of my lists have swift sp. on them. Now you could see them nesting at a waterfall and get easy, definitive views but that’s also easier said than done.

Thicket Antpitta

This bird is a classic heard only species. Go birding around Arenal and some other places and oh you will hear it! You’ll probably hear it so much you’ll get tired of its rising whistled song. However, you won’t tire of seeing it because sadly, you probably won’t. Ok, you could but you should know that you might need to hear 7 different birds before having one close enough to try and actually see. Then, you might also have to wait until it hops into view. It can be done, I have even shown it to groups of birders but it’s not the easist of birding tricks to accomplish.

The Three Leaftossers

With a name that sounds like an insult, maybe these birds shouldn’t be blamed for being so reclusive. Like the other birds on this list, none of the three species in Costa Rica are very common but they sure aren’t rare either, especially the Middle American Leaftosser. Even so, they can be very difficult to see. Looking just like the deeply shaded muddy ground doesn’t help.

Nightingale Wren and Scaly-breasted Wren

In being all about the singing, this pair of little forest gnomes are like antpittas. They are easy enough to hear and do have lovely voices but they seem to be distinctly opposed to being seen. As with antpitta viewing, a heck of a lot of patience can be required. They aren’t rare but knowing their songs is the key to wren viewing happiness.

Sulphur-rumped Tanager

No, it’s not actually rare! Look for them the right way in the right places and you can see this uncolorful yet cool rainforest tanager. Knowing the call helps along with accepting that you might see a dark gray bird with white tufts at the bend of the wing and NOT a bird with a yellow rump.

Veragua Rainforest is the best site for it but the tanager also occurs in southeastern Costa Rica from Panama on up to Barbilla National Park.

In Costa Rica, these bird species are far from impossible to see but you will need some luck. You might also need a birding hat trick or two, maybe a knowledgeable guide. Sharp eyes and lots of patience can also work wonders but for this dirty dozen, it’s best to lower the expectations. Lower that birding bar enough, stay focused, and you actually might see them along with a bunch of other birds from a 900 plus species list.

Leave a Comment