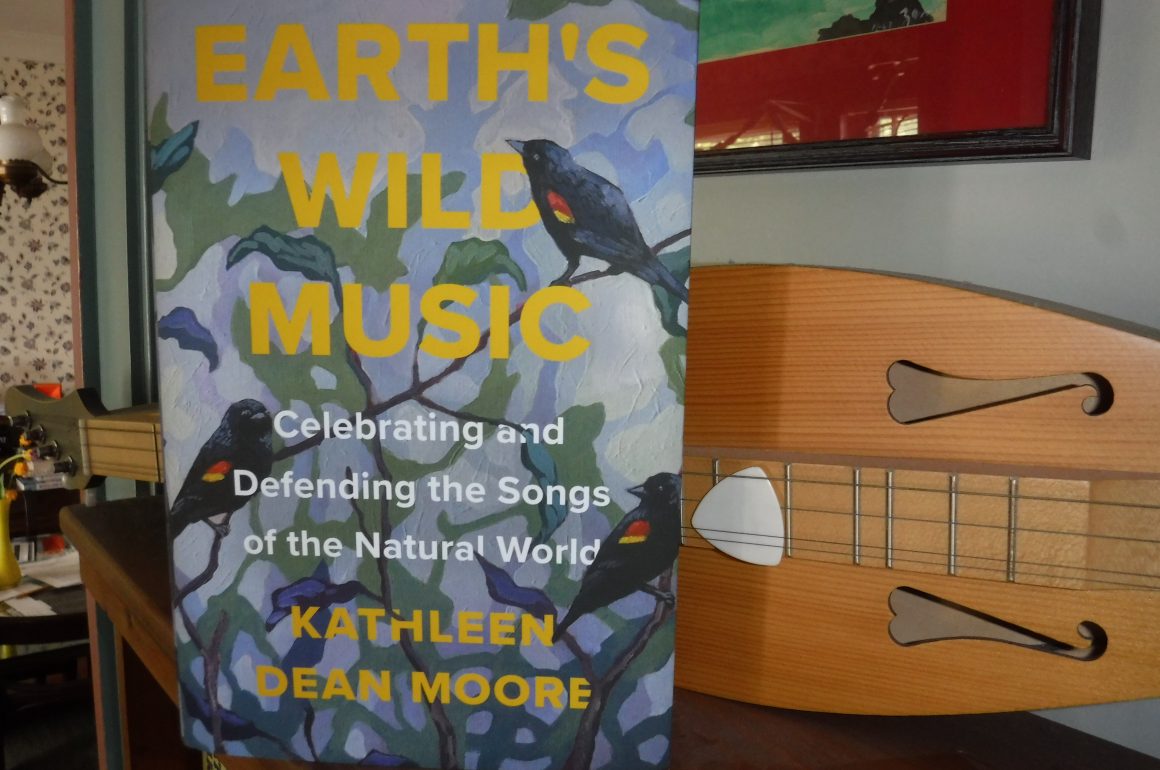

A fine idea for a nature book is promised by the title and subtitle: Earth’s Wild Music: Celebrating and Defending the Songs of the Natural World. And what an attractive cover it has, filled with blackbirds against a blue and purple sky.

But despite what one might have hoped and expected, the book isn’t about the sounds of nature, not really. It’s about the author, Kathleen Dean Moore, and the “drenching grief” she feels when she considers what is being lost in the Sixth Extinction. She does tend to wear her environmental beliefs and bromides on her sleeve.

The book consists of essays and stories, written in the first person, most of which have a connection, sometimes a tenuous one, with the auricular. The reader gets to know that Moore loves the song of the Meadowlark, and the sight of whales, and other natural things and beings and sounds and emanations. In general she has, as she says, a “deep love for the world’s music.”

The best critique of this comes via a story she tells on herself: she spoke to a convention of national park rangers, after which one of them commented “I like what you say, but I wonder if you couldn’t say it without using the L-word.”

She also likes to wag her finger at you – you know who I mean: you – for your complicity, as an individual and as a member of the species, in the supposed imminent destruction of the planet. Thus the book is a call to arms, and perhaps a necessary one.

But calls to arms can easily turn, via Moore’s pen and her voice, into hectoring: if you are an “inattentive citizen” who, “distracted or dozing,” won’t step up, you are guilty of “moral failure.” “Those who fail to respond to the emergency call,” she warns ominously, “become part of the storm itself.”

There’s something off-putting about her prose – it’s immensely earnest, precious, and by turns giddy and despairing (“If there is a sadness as big as the galaxy, I feel it now”), so that neither of those latter two emotions is very believable. This can be cause for a certain amount of teeth-gnashing by the reader.

And she’s overfond of alliteration, as in, for example, “Those who notice the spreading soul-sickness swallow sour pills of confusion and regret.” Huh?

There’s nothing wrong with alliteration. Used well, it can be, on its own, a clever and effective kind of metaphoric device. But it has to make some kind of sense (unlike, say, “we inhale the droplets of death that our culture carelessly causes”); should never be cute or forced or written for its own sake; and, above all, should be used sparingly. Moore falls afoul of all three of those.

There are things to admire about Kathleen Dean Moore and her book. Anyone of a certain age who sleeps outside in eleven-degree weather, as she does, has already established her bona fides as an outdoorswoman. She comes from a good line and a good part of the world: her father was a ranger in the Rocky River Reservation, which place is one of the delights of living in Cleveland. (She now lives in Oregon and Alaska.) When her third-grade teacher mocked her for reporting that passenger pigeons had once, numbering in the billions, blacked out the American skies (which is true), her father went in to the school to give the teacher a dressing-down. The world needs more fathers like that.

And Moore does, occasionally, leaven the breastbeating with a bit of humor. The day before she was to give a lecture to an environmental group at which she had specifically been asked to talk about what reasons for optimism might exist, she fell down a grassy slope and broke her ankle in three places — after which she texted the group from the emergency room: “Broke ankle. Cannot talk to your group about hope.”

There are items to learn from the book – things about the natural world, which is what, after all, the title and subtitle had promised. This reviewer, for example, did not know the word “samara,” as in — alliteration alert! — “a single samara spinning into the shade of a pumice stone.” (This comes in Moore’s discussion of the landscape around the volcanic Mt. St. Helens.) It’s a dry, indehiscent one-seeded winged fruit, such as that of the maple or ash.

Moore is a writer and environmentalist of some renown, and has published a number of books. This one, Earth’s Wild Music, got a very favorable review — a rave — in the WSJ.

The point is that there are, evidently, plenty of readers who will lap this stuff up.

Other readers, less patient, less charitable, less willing to wear the environmental hairshirt that is so in-style these days, may find her writing in Earth’s Wild Music to be at once cloying and shrill – not a good combo.

_____________________________________________________________________

Earth’s Wild Music: Celebrating and Defending the Songs of the Natural World. By Kathleen Dean Moore. Counterpoint Press, Berkeley, 2021, 249 pp., $26 (US), $34 (Canada). ISBN 978160093676.

One of the best “environmental” books I have read is a small paperback–SIMPLE IN MEANS RICH IN ENDS: PRACTISING DEEP ECOLOGY. (Bill Devall 1988). From this book, and the principal tenet of the once popular deep ecology movement of the 80’s, is that everyone who wears the “environmental hairshirt ” must obliterate any notion of moral obligations in our relationship to the natural world (just as we there is no no moral obligation or duty that bonds us to our mother and father), but instead identification. As Devall says, “…humans have limited ability to love from mere duty or moral exhortation.’