I can still vividly recall encountering my first Little Egret. I was on a family holiday with my parents, and swimming in the sea close to the resort of Sitges on Spain’s Costa Brava. I looked up and saw this wonderful white bird, with black dagger beak and black legs, flying over the sea just 20 yards from me. I couldn’t believe my luck: it was a bird that I’d always wanted to see. At the time Little Egrets were rare vagrants to Britain, so my chances of seeing one at home were extremely slim.

Not Cattle Egrets, but Little Egrets feeding with a cow on a Greek marsh

Now, several decades on, the Little Egret is a familiar bird throughout much of the southern Britain, and though it’s more common in coastal counties, it is widespread inland, too. Little Egrets first started breeding in England in 1996, when a pair fledged three young on Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour, on the south coast. In the same year another pair raised two young in Cornwall. Since then the increase of this attractive small egret has been nothing short of extraordinary. By 2001 the number of breeding pairs had passed 100; in 2015 it reached more than 1,000 pairs for the first time. Most of these birds remain over winter when they are joined by additional birds from the Continent. I haven’t found an up-to-date estimate of the current breeding population, but it’s probably around 1,500 pairs.

The lores of the Little Egret change colour for a short period in the breeding season

Little Egrets have bright yellow feet, except when covered in mud

Little Egrets are social breeders, and most nest in company with Grey Herons. Remarkably, it isn’t just the Little Egret that has colonised England. In 2010 Great White Egrets nested for the first time, on the Somerset Levels. Colonisation was slow, as by 2017 there were only an estimated 10 pairs, but today there may be as many 80 or more. It’s a bird I now expect to see on most excursions, for they are not only large and conspicuous, but becoming increasingly widespread. They are not restricted to England, either, as last year a pair bred in Scotland for the first time, on the RSPB’s Loch of Strathbeg reserve.

Big and elegant, Great White Egrets are a welcome new breeding bird in Britain

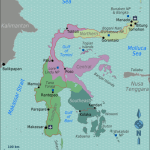

Great Whites have now colonised much of western Europe. Sixty-five years ago their only nesting site in western Europe was, I believe, on Neusiedler See in Austria. They first bred in Spain, in the Ebro Delta, in 1997, but by 2011 there were 53 pairs found in Spain, at five different locations. Today they are widespread across Iberia.

A Great White Egret feeding on a Suffolk reserve, May 2025

Great White Egrets feeding with Spoonbills and a Grey Heron at Bharatpur in India, March 2017. These egrets have a huge worldwide distribution

The wing of Great White Egret

Curiously, the third egret to become established in the UK, the Cattle Egret, made a somewhat faltering start. Though these small egrets first nested here in 2008, it took some time before they became more firmly established. It is only in recent years that they have become regular breeders, but like their cousins, they are clearly here to stay. This is hardly surprising, as the Cattle Egret is a bird that has massively extended its global range, most notably colonising the New World in the early part of the 20th century. In Europe they used to be confined to the south of Spain, but in recent decades they have spread steadily north, so their arrival here was hardly unexpected.

Cattle Egrets flying over a Menorcan marsh. Once a rare bird in the Balearics, they first nested on Menorca in 2006

A Cattle Egret attending an English cow. Holkham, North Norfolk, November 2023

Cattle Egrets are highly social, and you rarely see single birds, as they are usually in flocks. I’ve never seen more than 20 at once in England, but some big flocks have been recorded in in recent years. The biggest I have heard of was a gathering of nearly 700 birds at a roost on the Somerset Levels. And though they are called Cattle Egrets, they are just as happy attending horses, or even sheep.

Cattle Egrets are easily recognised by compact body and short beak

Quite why all three egrets should have finally colonised the British Isles is probably explained by global warming, for our climate is no doubt more attractive to these birds now than it was just a few decades ago. Lack of persecution is another factor. At the end of the 19th century they were shot in their thousands for their so-called osprey feathers (the plumes or aigrettes they develop during the breeding season). These feathers were used to adorn ladies’ hats: the formation of the Society for the Protection of Birds (now the RSPB) was largely due to a few enlightened women who were determined to stop this trade. Incidentally, it wasn’t just the adults birds that died: they were shot during the breeding season, leaving the chicks to die in their nest.

Today these egrets are a welcome addition to Britain’s avifauna. For birdwatchers of my generation, they remain something a of a novelty – who would have thought 40 years ago that we would have three species of egrets breeding in Britain?

Thanks David.

Very welcome summary on these “new” birds to the UK.