When I grew up in the seventies we didn’t have global warming, we had global cooling (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_cooling). Consequently, the summer weather was awful, always. Continuous drizzle, gales and the lead-grey sky merging seamlessly with the tarmac of the roads. Surrounded by damp greyness, we would try to enjoy our Dutch summer holidays. My Dad had nothing to throw at this misery but unfounded optimism: “I can see it clearing up any time now”. My advice to climate deniers: why deny a good thing – sing the praises of climate change… But, thanks to a lot of CO2, summers are great now and I spent one of those summers on the island of São Tomé.

Formerly a Portuguese colony, now with the island of Principe a proudly independent nation in the Gulf of Guinee. I was drawn to São Tomé because of the large number of birds named after the island, and in particular the São Tomé Grosbeak. This bird had been extinct for more than a century before it was rediscovered – a Lazarus species! Plus, there are more endemics on São Tomé than on the Galapagos.

My selected guide was the gentleman who claims to have rediscovered the grosbeak – Antonio Alberto. Although his detractors would say he was two years’ old when that happened he is undeniably a good guide. He has remarkable bush skills and as a former poacher he knows where all the birds are that he didn’t eat. I made contact (+239 995 six one six two) and paid half the fee upfront. A few weeks later I received a WhatsApp from Antonio telling me his friend’s car had broken down and he needed more money upfront. Not even bothering to question the logic of the request I made another trip to Western Union and voilá. Needless to say, I did not tell my wife about any of these financial transactions, and I may have been quite scarce on details overall. Omission, the secret to a long and happy marriage.

We flew to São Tomé, got through passport control with amazing speed and checked in the resort where my wife would be enjoying the spa and pool while I would be camping in the rain forest. Antonio showed up as agreed and we were off to Monte Carmo in the Parque Natural Obô de São Tomé. Access to Monte Carmo is through a 2,500 ha oil palm plantation. The palm oil company’s website is very positive about the socio-economic benefits for the local population but the people we met were adamant about not being paid a living wage. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle, but we will never know since the locals can’t afford a glossy website. Once we crossed the park border it started to rain. I looked back at the oil palm plantation just behind the park boundary marker and the sun was still shining there. The difference in micro-climate between the plantation and the rainforest couldn’t have been clearer. The plantation owes the rainforest, that’s for sure.

And up we went. The mountain is covered with granite boulders, very slippery mud, and tangles so I fell a lot in the mud. Antonio didn’t, not even one polite slip to make me feel less inept. I would have been very cross with him if this guy weren’t going to show me birds… Sensing my irrational emotions Antonio pointed out the São Tomé Ibis just behind us and all was forgiven. Such a wonderful person! We made camp at the “roça” – the ruins of a cocoa plantation house, ate a one-pot meal flushed away with palm wine, conversed with a São Tomé Scops-Owl and slept like logs while the São Tomé Free-tailed Bats flew all around us.

It really never stopped raining in the two days and one night on the mountain. I was soaking wet – there even was water behind my ear drums – but the birds were amazing. Two of the last 40 Newton’s Fiscals, plenty São Tomé Oriole, Giant Sunbird, São Tomé Short-tail – pretty much every target bird, except the Lazarus. After a depressing walk back through the birdless palm plantation with just one (undoubtedly company-sponsored) São Tomé Weaver we were picked up by Antonio’s friend who drove us back to Santana in his striking canary-coloured car.

Any car called Jesus was bound to keep us on the straight and narrow. But while we did go straight, the narrow road decided otherwise and made a curve. We slammed into a tree but miraculously nobody was hurt, and the car continued to be roadworthy. Roadworthiness is defined in the insurance policy smallprint as “able to drive off notwithstanding severe structural damage”. Safely back in the hotel I jumped in the pool to dry, had a cold one and told my wife about the adventures in the national park. She just shook her head in disbelief (?), despair (?), pity (?). I left out the accident from my gripping yarn – no need to add “worry” to this list of emotions (omission etcetera, see above).

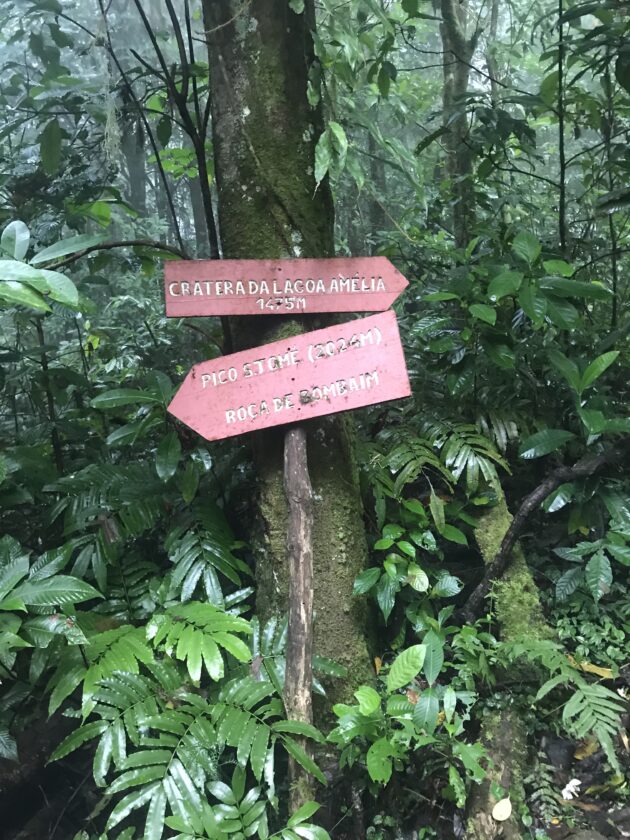

On my final day with Antonio we set out to the National Park of Obô again but now followed the Lagoa Amélia trail to look for the São Tomé Grosbeak. This is the place where Antonio had rediscovered the bird and after having heard grosbeaks calling throughout the previous days, my expectations were high. I continued falling flat in the mud on the way up so Antonio made me a walking stick. I still fell a lot but now had a stick to hold on to – I do believe I looked more dignified as a result. Alas, the mountain was covered in a thick low-hanging cloud with almost no visibility. We walked for hours to each one of Antonio’s favourite spots and found nothing. A poorly viewed São Tomé Bronze-naped Pigeon flew up, disappeared into the mists and we were surrounded by an eery silence once more. Antonio was about to give up but for some reason I thought of Dad. “Give it a minute, I can see it clearing up any time now”, I shouted to Antonio. And then, miraculously, the cloud lifted for just a minute and in that minute we saw it: a chunky little brown bird with a ridiculously large beak, eating a flower bud.

Beautiful story. Thank you for sharing!

Well Peter great lines about birding in São Tomé. Must say, after much work never got the sea the Grosbeak but every other bird was well worth the memories I keep. Thank you.

Love it! I dream of STP, so much so that once I applied for a job at Principe.