I’ve decided to get into the bird tour business. I mean, how hard could it be? Get up early, point at lots of birds, go back to the hotel for celebratory wine. If any birds give trouble just make up an answer, then say it with confidence. It isn’t like the punters will know any better, or care, so long as it counts as a tick. I can’t lose. Lacking, as I do, a birding reputation that would make people part with cash for my time I’ll have to go for the rarity hunters and put together an itinerary of highlights that can’t be missed. Luckily, I have just the mega tour I need, right here in the islands I call home. Guaranteed to produce birds you’ve never seen before or your money back!

I’ll pick you up at Auckland after your long international flight, and after a quick stop at your hotel to freshen up we’ll head to the Ark in the Park to pick up your first star North Island endemic, the Huia. This outstanding member of the wattlebird family is unique among songbirds in having different shaped beaks for each of the sexes. Filling the niche of the woodpecker here they use their small and long bills to explore and hammer through rotting wood and bark for insects. We’ll also be on the lookout for the melodious North Island Piopio. This drab brown denizen of the undergrowth is like no LBJ you’ve seen before, as it is actually an oriole and is tame and confiding, allowing mega looks once you’ve located this accomplished mimic. We’ll also keep our eyes open for several members of the New Zealand wren family. One of the oldest families of songbirds, which broke off before the oscines and sub-oscines split – and before New Zealand and Antarctica did! Here we should see the flightless Lyall’s Wren, once called Stephen’s Island Wrens (after the island they were first described from), as they scurry around the forest floor like mice! Also on the ground you’ll see your first Finsch’s Duck. This attractive relative of Australia’s Maned Duck is the most common duck you’ll see on the tour, but visitors always love seeing them and their ubiquity doesn’t detract from their attractiveness. And of course you’ll be keen to keep an eye open for Mantell’s Moa, one of ten species you should see on your tour. This species, the smallest, is endemic to North Island and should be fairly common in the wet lowland forests.

Huia

After a night spent in Auckland’s more seedy establishments we’ll be up bright and early (alka-seltzer provided free of charge) to head east. Stopping briefly at Miranda on the Thames Estuary for shorebirds and your first crack at the curious and clever New Zealand Raven, we’ll head into the kauri forests of the Coromandel. This should give us our first crack at one North Islands most astonishing birds, the North Island Giant Moa. This extraordinary and massive bird was once thought to represent two species, but is now know to instead represent a great example of sexual dimorphism, with males weighing half as much as the females. We’ll also have the chance to pick up flocks of fast moving Little Bush Moa in the denser undergrowth, and another chance to get Mantell’s Moa if we missed it earlier. Of course, excited as you will be by these magnificent ratites, we have other targets here. We’ve got a Forbes’ Harrier nest stakes out at Castle Rock. This massive harrier is unusual for having short wings adapted for a life in the forest. Closer to the ground, the bizarre Snipe-rail may be picked up here. In a world filled with flightless rails this flightless rail has shorter wings than any other, suggesting this is one of New Zealand’s oldest species of rail. It certainly has no known relatives. The sheltered bays of the Coromandel are home to another endemic, the Southern Merganser. This fish hunting duck ranges from the northern tip of New Zealand to the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands (after which it was first named) but is common nowhere.

Next we head towards the wine area of Hawke’s Bay and, after wetting our whistle at some of the delightful vineyards we’ll make for Lake Pouwaka, one of New Zealand’s premier waterbird destinations. Here we’ll pick up Scarlett’s Duck, a rare New Zealand species related to Australia’s beautiful Pink-eared Duck, as as the utterly unique New Zealand Musk Duck. Well, unique bar its Australian relative. The site is also the best in all New Zealand for the very rare New Zealand Stuff-tailed Duck. As we search for the retiring New Zealand Little Bittern in the reeds we should come across plenty of the local race of the Black Swan, Hodgen’s Moorhens and New Zealand Coot, if for some reason you’ve missed them until this point.

We’ll head down to Wellington via the central plateau, which holds the largest numbers of the North Island Goose in its open areas. This massive relative of the Cape Barren Goose is a real relic of Gondwana, and shares the open ground with the bulky Stout-legged Moa and the delightful New Zealand Quail. Keep your eyes open for Bush Wrens too.

The forests around Wellington will let us clean up any North Island endemics we may have missed. The North Island Adzebill is one such endemic, a massive member of an endemic family related to the Kagu and Sungrebe, this large forest floor predator should be an easy find here, hunting tuatara and weta (we’ll open a couple of Tuatara Beers to celebrate). Also easy to find here is the Moho, North Island’s version of the Takahe. After a night in Wellington, where along with Tuatara we’ll be sampling the Tui and Moa beer (Weka cider or Fantail wine for those that don’t like beer), we’ll board the morning ferry to Picton and South Island. Hopefully you haven’t drunk too much the night before as there will be plenty of bird watching from the ferry, picking up albatrosses and shearwaters like Scarlett’s Shearwater.

Once you’ve had a glass or two of the famous Sauvignon Blanc in Marlborough after the ferry ride we’ll drive to Nelson Lakes National Park to start grabbing the South Island species. One of our main targets here will be the tiny and rare endemic Long-billed Wren. This tiny flightless creeper uses its massive (for its body size) bill to find insects in the bark of trees. We may also find the largest of the New Zealand wrens, the Stout-legged Wren. Like many of its relatives, this species was also flightless. On the larger side of things we could find the South Island Adzebill as it stalks the forest in serch of prey, and this will be our first chance to find the South Island Giant Moa, the largest of New Zealand’s birds and one of the largest in the world.

Night here should produce some of the best spotlighting of the trip. Everyone wants to pick off the most fiercesome night predator here, the Laughing Owl, but we’ll also be out looking for the New Zealand Owlet-nightjar. One of the oddest members of an odd family, it is the largest owlet-nightjar, and also the only one that s flightless, and the sight of a flightless grey shape scurrying across the forest floor in search of prey is not one you’re likely to forget. Nor is the sight of the Greater Short-tailed Bat, which can still fly but instead chooses to scurry across the forest floor in the manner of a shrew. There aren’t many mammal ticks on this trip, but the ones you get are pretty remarkable.

Heading South to the Middle Earth scenery of Arthur’s Pass and we’re in real moa country now. Here we find two of the most interesting members of the family, the Crested Moa, unique of course for the shaggy crest on its head, and the mountain-goat-like Upland Moa. The Upland Moa’s long windpipe gives it a particularly striking call, an evocative sound you’ll come to associate with New Zealand stunning mountain scenery. The South Island Goose can also be found foraging in the open areas, even larger than its North Island cousin.

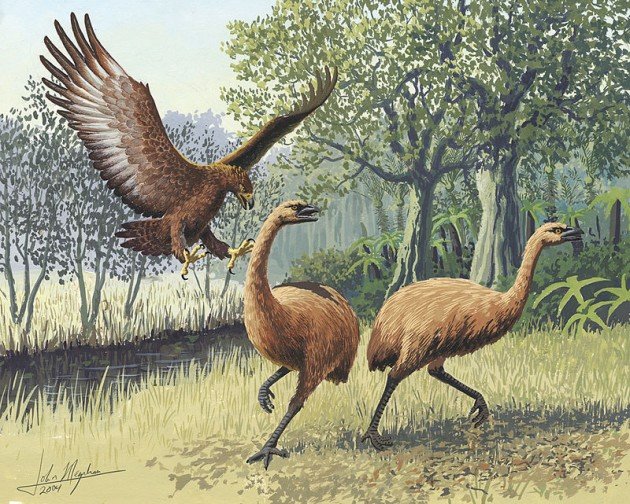

Down the mountain and into the drier Cantebury plains, and things get really exciting. If we didn’t get one in Nelson, this is the place to pick up the South Island Piopio, as well as the grey ghost of the forest, the South Island Kokako. And along with the South Island Giant Moa, which never get dull to be honest, we have two more to hit up here, the Eastern Moa and the Heavy-footed Moa. But our excitement at seeing moa here isn’t just for themselves. In Cantebury, where there are moa there might be Haast’s Eagles. We’ve got a couple of stake outs where we can watch not just for this raptor, the world’s largest, but where moa kills can sometimes be seen too. There are few sights on Earth more astonishing than the largest flying predator making its kill. And what better way to celebrate than to head out after dark, beer in hand, and listen to the amazing, and terrifying, rodding call of the South Island Snipe?

Next we head to Invercargill. We may have reached the bottom of the South Island but we haven’t reached the end of the tour. After checking the local beaches for the South Island Yellow-eyed Penguin, we’re off on a boat for the tour of New Zealand’s offshore islands. These range from the Subantarctics, where we’ll look for the Macquarie Island Rail on Macquarie Island (actually owned by Australia but biogeographically New Zealand), the Campbell Parakeet on Campbell Island, before our first big stop, the Chatham Islands. Our main targets will be the big three, three genera endemic to the group; the massive flightless Hawkins’ Rail, the smaller and odder Hutton’s Rail (perhaps related to the Snipe-rail), and the enigmatic Chatham Duck. The islands have a third rail (but not a dangerous one) called Dieffenbach’s Rail, one of many species birders familiar with Pacific species will recognise as being related to the Buff-banded Rail. Like the related Weka from New Zealand, and so many of the rails we have seen, it’s flightless. Not flightless is the Chatham Coot, but this species is unique for having highly developed salt glands, which help it deal with island life. On land in the forests of the island we’ll be looking for Forbes’s Snipe, as well as a number of insular relatives of mainland species, such as the Chatham Bellbird, Chatham Fernbird, the Chatham Raven and the inquisitive and very clever Chatham Kaka.

Our tour of the islands even present chances to resolve longstanding mysteries. Is there a species of scrubfowl in the Kermadecs? What about a parakeet on Macquarie Island? Do the Auckland Islands have a species of raven? There are reasons to think all this and more may be possible, and it’s exciting to have the chance to look.

Our tour ends on Norfolk Island. Like Macquarie, it is politically Australian but biogeographically a mix. Here we’ll find New Zealand’s only thrush, the Grey-headed Blackbird, it’s only cuckoo-shrike, the Norfolk Triller, and its only starling, the Norfolk Starling. Familiar with New Zealand birds as you will be by now you’ll hav no issues picking out the Norfolk Kaka or Norfolk Pigeon, but there’s a distinctly Pacific feel to the Norfolk Ground-dove. And birders familiar with Australia will certainly recognize the local race of the Brown Goshawk.

So, what do you think? With astonishing birds like that to bring the punters in, I can hardly fail, right?

…

Extinction is forever. A species, wiped off the earth, never to exist again. What a horror! What a disaster! What a wrong!

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

But, in the wider view of things, extinction is necessary. It is what drives evolution. Extinction is what befalls the species that fails to adapt, to survive, to thrive. Most species go extinct. That is just the hard, cold reality of nature, red in tooth and claw.

This is not to say that we should sit back and let the Holocene Extinction continue. No! We must fight to save every species we can, every ecosystem, every niche.

It is the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, once one of the most abundant species in the world. In order to raise our awareness, to remind us of what we have lost, and to inspire us to fight for Every. Single. Species. we are hosting Extinction Week here on 10,000 Birds from 7 September to 13 September. Come back, click through, read, learn. And get angry and take action.

…

A brilliant idea and very well-written. This is an amazing post. It took me a while to fully appreciate that all of the birds on this itinerary are gone. How can so much bad happen to one area?

Hey Steve, thanks for the comment. I talk about what happened to new Zealand here http://10000birds.com/the-remarkable-coincidence.htm