Where do you go to bird, when you know you might not be able to go anywhere else?

I suspected that we, here in Michoacán, México, might be about to lose our permission to leave our homes altogether for the next stage of the COVID-19 crisis. So, on April 13th, I chose to go back to the same site I visited on my first outing of 2020, Lake Cuitzeo. As it turned out, my suspicion was correct; since that day, all my outings have been “in-nings”. I am now developing a close relationship with the roof of my house.

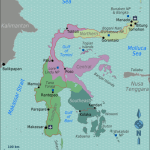

Perhaps one of my reasons for going to the lake was that it guarantees more species in one day than any of my other sites. But I am also always eager to get a better handle on the migration dates for our wintering species, and April is a great month for that. So off to the lake I went, to see which ducks and shorebirds were still here, and which had already left. And, just maybe, to find some surprise species passing through on their way north.

The lake had changed quite a bit since my last visits, in early and mid-February. Our 2019 summer rainy season had lower-than-normal rains, and the lake is now extremely shallow. This meant that the remaining banks of ducks were beyond the clear range of my optics. There was no doubt about the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of white breasts of Northern Shovelers. But it was impossible to tell whether any Gadwalls, American Wigeons, Northern Pintails, or Green-winged Teals remain. (I do not yet own a scope.) Closer to shore, a handful of Blue-winged Teals could be seen, along with some resident Cinnamon Teals.

But it was along the shores, with a wide variety of shorebirds, that things really got hopping. (Aided by the fact that I can walk the lake shores in total solitude, while watching ducks from the narrow causeways that cars use to cross the lake felt much less safe.)

Oh yeah. The Peeps are still here.

Oh yeah. The Peeps are still here.

There were Least Sandpipers on the lake’s south shore, and Western Sandpipers on the north shore. Both are beginning to show their reproductive plumage, which is a rare sight here in Mexico. But it was the Long-billed Dowitchers who were really rocking their breeding plumage. And there were lots of them! I usually see dozens of this species on the lake, but this time, there were hundreds. Almost all the flying birds in the heading photo above are Dowitchers (with American White Pelicans behind them), and those are only one part of the total I saw along both lake shores.

I never see Dowitchers here in May or June. So seeing this plumage is special for me.

I never see Dowitchers here in May or June. So seeing this plumage is special for me.

The Least and Western Sandpipers were not the only very small shorebirds by the lake. There were also a few Semipalmated Plovers, soon to head north. Just like Dowitchers, these shorebirds may be seen here ten months out of the year, but never in May or June. (How on earth do they breed so quickly up north?) The slightly more numerous Snowy Plovers, however, will stay right here; Lago de Cuitzeo is one of the few places where this species breeds in central Mexico. Of all North America’s Plovers that may migrate, only the Snowy and the Killdeer breed this far south.

This Plover is a Semipalmated, and should be leaving for Canada any day now.

This Plover is a Semipalmated, and should be leaving for Canada any day now.

But this Plover is a Snowy, and will stay right here. I’ll see you sometime this summer… I dearly hope.

But this Plover is a Snowy, and will stay right here. I’ll see you sometime this summer… I dearly hope.

Apparently, for this Killdeer, knowing it will be staying all summer is a pain in the neck.

Apparently, for this Killdeer, knowing it will be staying all summer is a pain in the neck.

As for those unexpected species passing through? Yes, there were a couple of those. I failed to get a photo of a beautiful reproductive male Townsend’s Warbler I saw. That would not be a surprise a few miles south, in Pine/Oak or Pine/Fir Forest. But this one was foraging among the thorny Mesquite trees on Lake Cuitzeo’s northern shore. I had never before considered that this species, between its wintering grounds in Mexico’s highland forests and its breeding grounds in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, would have to cross all sorts of desert. So there, I learned something new.

And I almost missed the other surprise of the day. Among all the reddish reproductive Dowitchers, I saw many similar birds in shades of gray and white. Since I am much more accustomed to seeing Dowitchers in their drab winter plumage, I assumed these birds had not yet changed their plumage.

The birds in question can be seen on the left and right of this photo.

The birds in question can be seen on the left and right of this photo.

Once I got home and saw my photos, though, it was clear their flanks were too strongly patterned, and the bills were too short. And I don’t know how I missed the size difference in the field. What could they be? Stilt Sandpipers! This shorebird is hard to see in my region, and I had never before photographed it in reproductive plumage. But I sure did this time!

I count at least 15 Stilt Sandpipers in this photo, along with several Dowitchers.

I count at least 15 Stilt Sandpipers in this photo, along with several Dowitchers.

Lago de Cuitzeo is a site where I regularly see 80 species in one day during the winter, and at least 60 during the summer. I am glad I chose it for what looks to be my last outing for a while. With so many species, I was bound to get good images of some other birds as well. I leave you with a few of these images:

This White-faced Ibis is also rocking its breeding plumage.

This White-faced Ibis is also rocking its breeding plumage.

A handsome American Pipit that will soon head north.

A handsome American Pipit that will soon head north.

Most of our winter Common Yellowthroats breed up north, but some are residents. Will I go, or will I stay?

Most of our winter Common Yellowthroats breed up north, but some are residents. Will I go, or will I stay?

Leave a Comment