Zach Schwartz-Weinstein is a writer, teacher, organizer, and birdwatcher who lives in upstate New York.

The ornithological practice of naming species after dead white people — almost universally dead white men, with the exceptions of Lucy’s, Grace’s, Virginia’s, and Blackburnian Warblers, (which are named for dead white women) is fundamentally an index of ornithology’s complicity with the history of European imperialism and settler colonialism. This is the same history of conquest and despoliation which now puts many of these very species in danger of extinction. We should stop naming birds, especially non-European birds, after European and Euroamerican naturalists and scientists, especially if we are committed to making the worlds of birds and birding accessible to more people than the demographics that produced the Audubons, Wilsons, Stellers, and MacGillivrays.

The racial politics of bird nomenclature are on the minds of many these days, thanks to a proposal authored by Robert Driver to amend the American Ornithological Union Checklist to change the english name of McCown’s Longspur. John Porter McCown, who shot the first recorded specimen of this species known to Euro-American science, was a Confederate general, a high-ranking officer in the insurrection led by the southern plantocracy to preserve and expand Slavery and the mode of white supremacy which it supported. Prior to serving in the Confederacy, Driver notes, McCown played leading roles in genocidal campaigns against indigenous peoples on the US-Canada border and against the Seminoles in Florida. “This longspur,” Driver writes, “is named after a man who fought for years to maintain the right to keep slaves, and also fought against multiple Native tribes.”

McCown is an extraordinary case. Most of the white people birds are named after are not directly culpable in settler colonial genocide and militarized white supremacy, or certainly not as culpable as McCown. But this proposal nevertheless sheds light on a broader problem: the practice of naming birds after white people inscribes the history of settler colonialism and indigenous disposession onto nonhuman animals, paralleling a similar writing of the Lockean logics of what the legal scholar Cheryl Harris has called “whiteness as property” onto the geography of the so-called New World, onto the very landscape itself. To name something is to have knowledge of, and ultimately power over it. Naming after, naming for, is a peculiar kind of gesture – it exercises power both in the way it writes over other possible names, and in the way it assigns particular names — names of white people — to things (and places) which more often than not have other, older names.

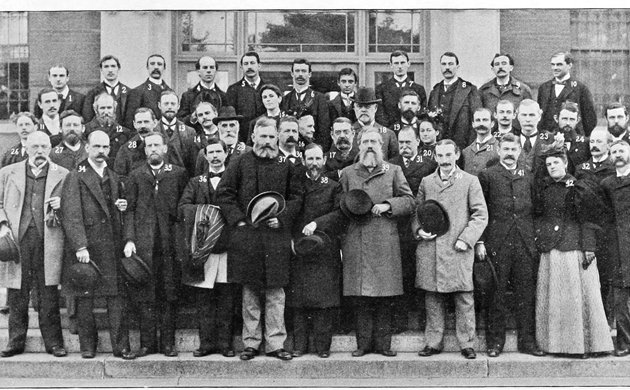

This writing of conquest onto the so-called natural world is an example of what the late Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano called the “Coloniality of Power,” a concept Quijano coined, and which many others have adopted, to describe the fundamental role colonialism has played in organizing modern social life and knowledge. It naturalizes the presence and dominance of men named Lincoln and Lewis and Clark and Cook and Townsend and Swainson and Cooper and Wilson and Baird and Franklin and Lawrence in North America, it reinforces the masculinist, imperialist myth of European exploration of the uncivilized frontier, and it obscures and forgets the profound violence those narratives mask and themselves do to the ongoing struggles of the descendants of the people who lived on this continent before Cassin and Brewer and Harris and Audubon.

Wilson’s Plover?

So, a proposal: let’s stop naming non-European birds after people of European descent. Let’s not, as has also been proposed, then, rename Saltmarsh Sparrow to honor Roger Tory Peterson, great though his impact on birding may have been. Let’s rename McCown’s Longspur immediately, but let’s also start renaming all of these other birds in accordance with distinctive features, behavior, or habitat. Where and when possible, we should use indigenous names. I propose this not out of the misguided notion that doing so will magically alter the ongoing social and cultural logics of domination and exploitation around which colonialism organized the globe. It won’t. But maybe it’ll help us remember that birds exist in relation to us, remember how their histories are our histories, and remember the ongoing histories of dispossession and violence which underlie even seemingly innocent activities like watching birds.

…..

Most birds were named by now dead white men who didn’t appreciate that most of the species they were “discovering” had already been discovered and had names. Most of the birds so named were named by men with the dead remnants of a bird in their hand and often the men doing the naming had never seen the bird in life. Geographic, honorific, horrific, and overly specific names abound much to the detriment of those who would like names to actually fit the creatures being described. And we poor birders have to use those names because otherwise no one will know what bird we are checking off our list and bragging about having spotted to fellow birders, bored families, and unimpressed romantic interests. Well, no more! We here at 10,000 Birds have decided to right some wrongs and improve the birding world by renaming birds the way they should have been named from Linnaeus to the present. (Or, at least, pointing out some names that suck.) Welcome to Bird Renaming Week, our week-long exploration of the names we put to birds and how they can be improved!

Most birds were named by now dead white men who didn’t appreciate that most of the species they were “discovering” had already been discovered and had names. Most of the birds so named were named by men with the dead remnants of a bird in their hand and often the men doing the naming had never seen the bird in life. Geographic, honorific, horrific, and overly specific names abound much to the detriment of those who would like names to actually fit the creatures being described. And we poor birders have to use those names because otherwise no one will know what bird we are checking off our list and bragging about having spotted to fellow birders, bored families, and unimpressed romantic interests. Well, no more! We here at 10,000 Birds have decided to right some wrongs and improve the birding world by renaming birds the way they should have been named from Linnaeus to the present. (Or, at least, pointing out some names that suck.) Welcome to Bird Renaming Week, our week-long exploration of the names we put to birds and how they can be improved!

…..

YES!

One question to ask is: Who gave the AOS the authority to name our birds? As Rick Wright points out in his blog post “The Official English Names of North American Birds” (http://birdaz.com/blog/2018/11/16/the-official-english-names-of-north-american-birds/), the AOS took this on in the mid-20th century after decades of saying their only concern was scientific names. So, they mandate and we follow. But, we don’t have to follow. This may lead to a bit of chaos in the field as people argue over the best name for Wilson’s Warbler, etc., but I already know several groups of birding friends who have their own names for birds. We create our language, not the other way around.

Great article and perspective. Thanks!

Fantastic article!

This seems to me something that has to be assessed on a case-by-case basis and written up into a proposal such as that for the McCown’s Longspur. I’m not sure the argument that McCown’s Longspur ought to be changed is the same as that for Wilson’s Warbler, to name just one. One is named for someone known for being a Confederate Civil War general and the other for a pioneering ornithologist, naturalist, and illustrator. Although both are dead white males, a reasonable person could nonetheless believe that one should be changed and the other is acceptable. While purposefully provocative, this might paint with too broad a brush.

For those who are truly passionate about the issue, it does not appear unduly difficult to submit a proposal to amend the American Ornithological Union Checklist.

We should take our lead from sports stadiums- go out for sponsorship deals and raise big bucks for conservation. The Burger Kinglet. The Taco Bell’s Vireo. The Citibank Swallow. Toss out the old and make big money for a good cause.

Tune in on Friday!

Renaming hundreds if not thousands of birds is a great idea, and it’s nice to know that the present political climate of social and environmental tolerance has given us the leisure time to sit back, relax, and spend all this energy writing about the need to gratuitously change English bird names rather than engage in more pressing issues.

However, if we’re going to be serious about this, let’s do it properly: Audubon was of French descent and the French kill millions of songbirds a year to eat (“lark-tongue pie, umm, delicious”), so naming Audubon’s Oriole for him is very offensive, let alone a supposedly conservation-oriented organization. And there are rumors that Lucy of Lucy’s Warbler fame was once unkind to her pet dog, and as we all know, pets—and dogs in particular—are sacrosanct, so it really is offensive to all pet owners to have a bird named for somebody who treated their dog poorly. And now we learn that both Grace and Virginia ate meat (can you believe that?!), which is truly offensive to all the vegetarians out there. Actually, come to think of it, having the US national bird—Bald Eagle—with a fully feathered head is surely an irony that offends millions of bald people, so that name should be changed as well… And while we’re at it, America is named for Amerigo Vespuccio, an Italian and very much a DWEM—Dead Western European Male—so now we need to change the names of two whole continents and all the bird names that go with them. Moreover, apparently Vespuccio in his later years taught at a Spanish school for “trade in the Indies” that would have sent sailors off to rape, pillage, and evangelize countless folks living happily without God in Latin America, which sort of makes McCown and Bendire look like nobodies.

Sure, English bird names are fun to think about and everyone can think of ‘better’ names for almost any species, but only somebody who had a humorectomy at birth could take this stuff seriously. We are all victims of history, and there’s no such thing as an innocent bystander. So can we please move forward rather than backward? Catering to people who manufacture PC rage and indignation to give meaning to their lives seems like a waste of everyone’s time, and the AOS should have a threshold of common sense when accepting proposals. But, that’s a drawback of so-called democracy, which today is defined as a form of government in which minorities have a disproportionately loud voice (what part of democracy do they not understand?). And if you think I’m anti-PC then please think again—because I really don’t tolerate people who are intolerant 😉

And one final thought to ponder: Given that almost all of the English language words we are using to communicate here were codified and defined by Dead White Males (DWM), including Noah Webster and his dictionary, then perhaps 10,000 birds should invent a new language altogether. I mean, it’s a bit hypocritical to write all this in DWM English—oh wait, but that would be silly, unlike derailing an entire communication system for bird names. And then one could argue about Webster’s views on the abolition of slavery, and thus should we reject written American English altogether? Or might we simply go outside and enjoy and appreciate the marvel of birds in life and not worry about what they are called? Hey, that sounds good to me, I’m out of here…

I mean, we can do both, yeah?

And I don’t agree with the slippery slope argument that eliminating honorific common names in birds means we have to suddenly reject written english. I know you’re being silly, but we can deal with the things we can deal with.

The ornithological community can do *this*, and if this is a good thing on its own merits, then they should.

There has been a bit of a buzz regarding bird names recently and I wonder whether there will be any uptick in the number of formal submissions to American Ornithological Union. The McCown’s Longspur submission is just a few pages, so anyone who feels passionately about this issue does not have an incredible burden in attempting to move the ball forward. It might even be an interesting project for a group or club.

What about birds named after DWEMs, but at one remove — such as Louisiana Waterthrush?

It gets worse. With the recent sordid news about MLK, King Eider and King Rail have to go. King Penguin too, if our jurisdiction extends that far. Also, who will be in charge of purging Latin names?

I am currently finalizing an exercise on the etymology of Maltese bird names. We have some dating back to the 1300. Generally speaking I am against changing established bird names as it creates so much confusion. In Malta, changes in names over time meant the death knell for local names as people switched to English names. I am not racist at all but removing names because of racism sound very stupid. Are we going to tear down monuments and architecture made by people whose actions we are now judging by today’s standards? Lets not allow racism to creep in the bird world, please. the world is bad enough as it is!

The biggest load of claptrap I ever read.

Are any of you actually birders, outside of your own gardens or is this just an extension of the movement that’s pulling down statues all over the World?

Leave politics oiut of the hobby that I’ve enjoyed for over fifty years.

America is not the only country to colonize with violence. History back to ancient times is full of war and slavery. Conquerers from Europe, the Middle East. Slaves built the Egyptian Pyramids. Should those be torn down? Are war and slavery to be tolerated? No, but you can’t re-write history on the planet to vanquish all the bad. We need to learn from it. And if you want to complain about only white men having birds named after them, where were the black scientists? If a black person discovered a species, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. Women are minorities, so we should leave the birds named after white women. Or can they only be named after black women? This is really ridiculous to have to break down everything in society and change it.

And while we’re rethinking bird names, can we please get rid of ‘American’ as a prefix, as in robin, oystercatcher, pelican, etc? Let’s call them ‘North American’. There are more robins in Canada than (US of) America.

If ‘American’ means ‘not South American’ then let’s be specific. Or call them something entirely different, like orange-breasted thrush, pied oystercatcher, white pelican, etc.

I’d suggest that, while it’s not an entirely bad idea, this by itself would be a symbolic move that would do little more than assuage settler guilt.

We need to seriously interrogate how birding itself is an activity of colonialism. It’s an imposition of settler epistemolologies. It’s an activity that, in many of its manifestations, constitutes an extraction of entertainment or at least pleasure from the stolen land by settlers. It’s an activity whereby settlers take up space in — and reinforce our notions of owning — what we call nature. In birding and in “being one with nature” we as settlers tend to naturalize (in our minds) our presence here, no matter how deep our respect may be for the land and the planet as a whole. And of course, even alongside such respect, there’s an inescapable degree of commodification: birding itself is a commodity from which some settlers profit.

There are actually birds named for dead Japanese aristocrats and imperialists, too… One notable example is the Mikado Pheasant (Syrmaticus mikado) from Taiwan, named in 1905 after Emperor Mutsuhito, the emperor of Japan. Taiwan had been absorbed into the Japanese empire in 1895 after the Japanese victory in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), so the Japanese were also involved in an imperialist project of naming and claiming. And yes, they were also highly connected to the AOU (now the AOS), and as scientists of color, networked in the Anglo-American world to claim dominance at least in knowledge of East Asian birds–with some, like Marquis Hachisuka Masauji, writing a book on the birds of the British isles (!) I’m writing a book on the topic, so these debates are fascinating to me, and indicate a long history of struggle for scientists outside of the Western world in making a “name” for themselves.

Stupid. Just stupid.

Wtf am I reading? It’s like a paranoid schizophrenic puked his inferiority complex on a birdwatching blog