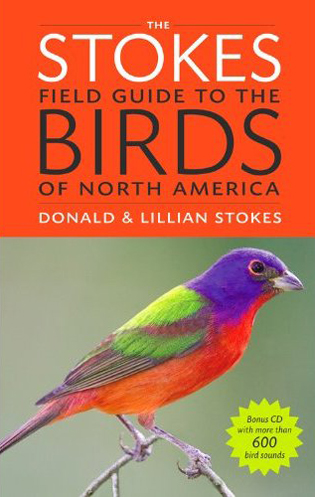

With a release date of 25 October 2010, The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America will  likely be showing up on the wish lists of many a North American birder this holiday season. Entirely illustrated by photographs, the main selling point of the new field guide is the sheer number of species and subspecies covered with excellent photographs. The back of the book claims 854 species and over 3,400 stunning photographs but I wouldn’t be surprised if those numbers were low because it seems like nearly everything is included. The 792 pages of the book are bursting with eye-popping images from the Painted Bunting on the front cover to the awesome flight shot of a Pileated Woodpecker on the back.

likely be showing up on the wish lists of many a North American birder this holiday season. Entirely illustrated by photographs, the main selling point of the new field guide is the sheer number of species and subspecies covered with excellent photographs. The back of the book claims 854 species and over 3,400 stunning photographs but I wouldn’t be surprised if those numbers were low because it seems like nearly everything is included. The 792 pages of the book are bursting with eye-popping images from the Painted Bunting on the front cover to the awesome flight shot of a Pileated Woodpecker on the back.

In between those covers are the birds of North America, a varied bunch that is handled relatively uniformly, at least within families. Every species is illustrated by at least two photographs and many by more than that. Almost every duck, wader, shorebird, larid, tubenose, and raptor has a flight shot included, and swallows and martins are particularly well-represented with beautiful, crisp, flight shots, which are not easy to get. The many plumages of gulls are illustrated with lots of pictures: most gulls have from nine to eleven shots included. Wood-warblers, especially the Bay-breasted/Pine/Blackpoll Warbler complex, are especially nicely-depicted. Unfortunately, most of the passerines lack flight shots, a shortcoming that leaves this field guide a bit below the bar that Sibley erected. But in terms of different plumages and distinguishable subspecies the Stokes include pretty much everything. Song Sparrows that look like Fox Sparrows, the wide variety of Savannah Sparrows, and a host of other subspecies and plumages are depicted. The only image that I thought should be included that isn’t is a juvenile White-eyed Vireo, though, of course, the description of the juvenile notes that the eye is dark.

Now that I have brought up Sibley I feel that I should at least briefly touch upon the painting versus photograph discussion for field guides. Rather than go into detail of the advantages and disadvantages of a photographic field guide versus a field guide that uses paintings I will let the Stokes speak for themselves, in words taken from the “How to Use This Guide” section:

Excellent, well-chosen photographs are always more detailed and more accurate than a drawing. This is particularly true when it comes to shape, feather wear, feather detail, ad color placement. Because a bird’s shape is a composite of so many subtly interacting components, it is rare that a drawing puts them all together accurately enough to get a true representation of a bird’s shape. To learn shape well, it is best to both look at the bird in the wild and study good photographs.

Personally, I tend to be a person who prefers paintings for passerines but multiple photographs for shorebirds and raptors. Whichever type of illustration one chooses there is always room to use the other and it makes sense to have both types of field guides so you can see the “idealized” bird typically represented by paintings and the “actual” bird typically represented by photographs.

And if one is going to own a photographic field guide for the birds of North America, the Stokes now have the most complete book on the market. Lillian Stokes is, as those who follow Stokes Birding Blog know, a heck of a photographer. Many of her images grace the pages of the field guide but photographs from well over one hundred other photographers are used as well. The time and care taken in choosing the photographs is evident, and I could not find a blurry, badly backlit, or poor photograph in the book.

Of course, field guides are about more than the images of birds. The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America is smaller than Sibley or Peterson but larger than NatGeo. As such, it will easily fit into one of the large pockets of my cargo pants. It feels solid and, though I did not try this, I bet I could dump a glass of water on it and wipe it off without causing any damage. The guide includes a “bonus CD” with recordings of some of the more common bird species, a nice but unnecessary touch (those who really want recordings will want more than 150 species and those who don’t want recordings, well, they don’t want recordings). That said, I did recently accidentally tape over my owl tape so I might just end up using the CD.

The species accounts are detailed, and, as promised at the beginning of the book, use “precise language to describe shape.” Each species has its ABA checklist code helpfully included next to its common name, a good idea that will help people get a grasp as to relative rarity. Just below the common name is the scientific name and the length of the bird. The descriptions of species often use ratios, like “wing length 2 1/2 X width,” which, while precise and probably helpful to some people, is not how my brain processes birds. The plumage descriptions are, of course, accurate, and very detailed and helpful and the descriptions of birds in flight are excellent, if somewhat clinical. The maps, designed by Paul Lehman and digitized by Matthew Carey are detailed and spot-on, though to save space they are rather small. The list of each species subspecies and hybrids is a wonderful touch; I can’t think of any other field guide that ever included such information.

Would I buy The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America? Well, now that I have been provided a review copy I don’t have to, but if I didn’t have a copy in my hands I would certainly want one. If you are a birder who likes using photographs for your bird identification you can’t go wrong with this guide. If you are a birder who prefers paintings you probably still want this guide if only to provide another point of view. If you aren’t a birder this is still a great book, loaded with excellent images that will help you figure out what exactly that weird bird in your yard is. I highly recommend The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America and think that it will be a nice inclusion to anyone’s library.

The Stokes’ guide was my first and really helped spark my interest in expanding my interest in making quick identification of migrants in my backyard. I’ll be asking for this one this year if I don’t get a review copy first 🙂

I like that ABA Code number in there too. It will help birders, especially new birders, recognize special sightings and report them. It will also help birders by making them question their rarity sighting a little bit more and hopefully help them get a correct i.d. I’ve embarrassed myself enough reporting rare birds that were really regular birds in a state of molt.

The ABA rarity code is definitely a nice touch. Ted Floyd’s Smithsonian Guide has them too, and of course the Collin’s European Guides have been doing something like that for a long time.

It’s incredibly useful, for precisely the reasons Idaho_Birder suggest.

Although I still feel that the Sibley Guide is the best North American guide (even with its slight shorcoming of not covering as many NA vagrants), there is a definite need for a really good and very complete photographic guide. This Stokes guide most definitely fills the bill. Photo guides don’t get any better. Frankly, I wouldn’t be without either guide. This Stokes guide is very well done and if you are interested in birds at any level I’d highly recommend getting the Stokes as well as Sibley. Both books are bargain priced considering the sheer amount of information and illustrations they contain. They’re must haves for any birder.