In six or seven months, the “best books of the year” features will come out in the important print and web publications. They will list ten or twenty or fifty titles, and will include, inevitably, Hunter Biden’s autobiography, and Volume 12 of Barack Obama’s, and other such works.

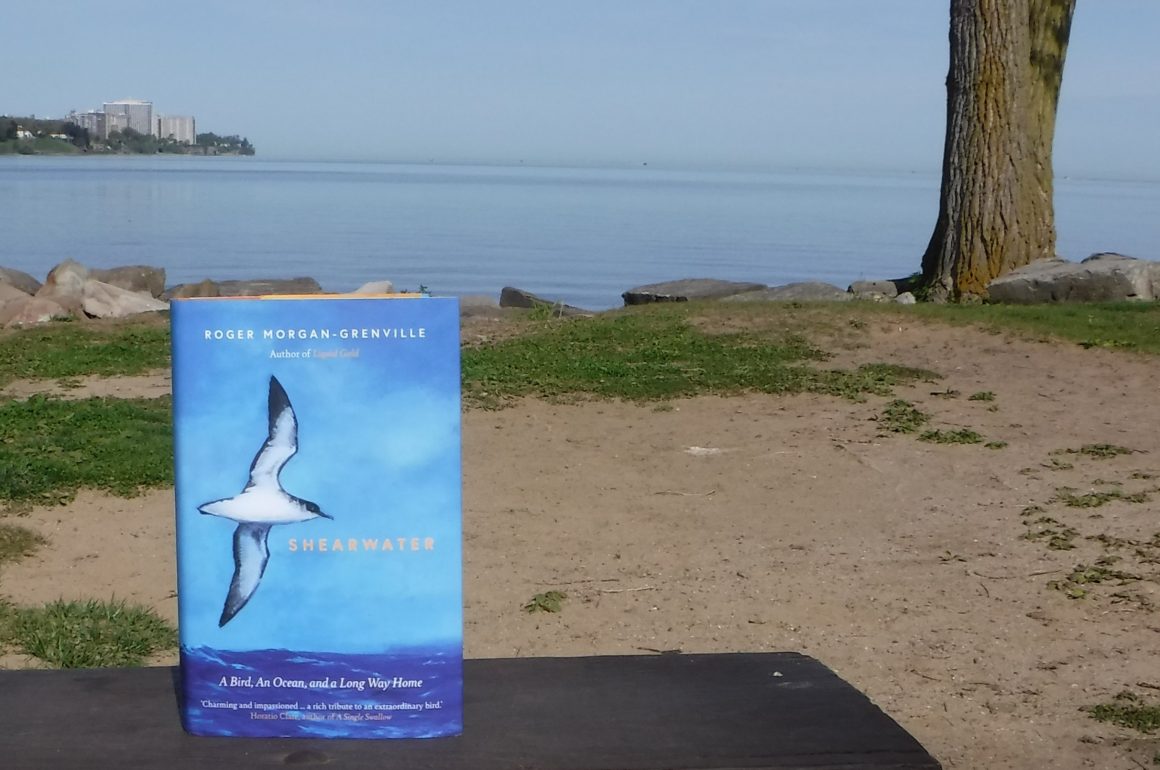

But if there is any justice in this world, there will be room on those lists for Shearwater: A Bird, an Ocean, and a Long Way Home, by Roger Morgan-Grenville. It’s that good.

On a day in 1971 — “Day 4233 of my life,” according to his schoolboy journal – Morgan-Grenville saw his first Manx Shearwater. It was Bird Number 83 on his life list, and it became, he says, his “metaphor for wilderness and adventure, always free, always out there, always just beyond reach.”

It’s easy to see why he was entranced, especially after he learned about these pelagic superstars. They hatch in burrows which are located (most of them) on a couple of islands on the British west coast. Sixty or so days later, they fledge and, with no guidance from their parents, take off across the Atlantic – the equivalent, Morgan-Greenville says, of a four-month-old human baby “walking out of the house to make its own way in the world.” For the next four years, the bird will not touch land.

Later Morgan-Grenville did a stint in the British army, when, on a voyage from Stanley in the Falklands to South Georgia Island, he saw his first Wandering Albatross, thus raising a question he has spent the most of the rest of his life pondering, as to his beloved Manx Shearwaters and others: “What happens with those ocean birds when they go out of sight?”

[Odd and irrelevant but curious factoid no. 1: this is the second book reviewed on this site in the last month written by a birder who, while serving in the British military, visited the Falkland Islands and was impressed by the bird life there, and thereabouts.]

Later still (near 60 years of age), Morgan-Grenville, in order to answer that “what happens when they go out of sight” question, decided to follow his Manxies, as faithfully as he could, for a year. As this map shows, he had set himself a daunting task.

They travel, in that year, 40,000 miles or more. They fly close to the water, exploiting “the differential between the low air pressure just above the waves and the higher pressure a foot or so above.” Absent mishap, they will live for fifty years. They were named for the Isle of Man but are no longer found there – the arrival of the brown rat ruined that home for them. (But there is, apparently, and thanks to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, some good news on the rat front in that part of the world.)

A few people share parts of this story and this book with the author – Ph.D. candidates and other seabird field researchers; and crusty boatsmen, some clued-in and some clueless, who guide him in various latitudes.

But the human star of the piece (though long dead when Morgan-Grenville undertakes his quest) is the grandmother with whom he spent his childhood summers at her croft on the Hebridean Isle of Mull. They were, he reminisces, “sometimes distanced, sometimes brought closer by the 50 years between us.”

Unnamed, she appears in his memories sporadically through the book: an individualist, a convert to Catholicism in a milieu where that was a ticket to total social and family ostracism, a World War II heroine of sorts who never mentioned the MBE medal she had been awarded, a devotee of disgustingly strong Turkish cigarettes and unsuitable music hall songs.

But the teenaged Morgan-Grenville knew, above all, that she was on his side, and that was all that mattered. That, and her love of the wild that she passed on to him.

[Odd and irrelevant but curious factoid no. 2: There is a band of some renown, an indie rock band, called Shearwater, whose lead singer has written a book to be reviewed on this site presently. Even more curiously, that book has, it appears, little or nothing to do with Shearwaters. But it does deal, in part, with bird life on the Falkland Islands. Stay tuned.]

Morgan-Grenville is a delightful writer, and uses more British idioms than you can shake a stick at (to use an American one). He has the advantage of a setting (for much of the book) in Scotland, where the place names (the Isle of Muck, Lunga and Dutchman’s Cap, Eigg and Rum, Muckle Flugga Point, and “Ben More, Mull’s only Munro”) are as weird and wonderful as any you might find in southwestern West Virginia — which is perhaps not surprising since many of the original settlers of Appalachia were Scots or Scotch-Irish.

He ends this lovely book, in an Afterword, warning of various environmental dangers to seabirds, and his writerly tone here is perfect: serious, but not hysterical or preachy, with a gleam of hope evident.

Manx shearwaters are, in relative terms at least, thriving. They’re lucky: unlike albatrosses and other seabirds, they are not ship followers and so can mostly avoid guy-lines and nets. They fly too low for wind turbine blades, and dive too shallow for long-line hooks.

Still, ninety percent of the world’s seabirds have plastic in their stomach. For that reason and a hundred others, the situation seems dire.

But human beings are not uniformly evil. Stupid, yes, maybe, but not evil. Here’s Morgan-Grenville’s conclusion about homo sapiens’ current efforts to reverse seven decades of decline in seabird biomass: “I was struck not by how little people were already doing, but how much.”

________________________________________________________________________________________

Shearwater: A Bird, An Ocean, and a Long Way Home. By Roger Morgan-Grenville. Icon, London, June 8, 2021, 281 pp., $27 (US), £16.99 (UK). ISBN 978-178578-720-1.

Thank you for this wonderful book review. Sounds like an intriguing and well written book. I’m looking forward to reading it myself!