Do Brown-headed Cowbirds really smell like freshly baked sugar cookies? Do Dark-eyed Juncos really smell like leaves and dirt or “ferns and Celestial Seasonings’ Country Peach Passion Tea? Do birds use odors and a sense of smell to communicate with each other? The Secret Perfume of Birds: Uncovering the Science of Avian Scent focuses on this last question, but you might find yourself fascinated by the first two, which come early in the book but linger on in the imagination as author Danielle J. Whittaker’s adventures in olfactory research take unexpected turns into genetics, chemistry, and the halls of academia. I have never even thought to smell a bird, and I don’t know if I will ever get close enough to a wild bird to do so (also, I have a lousy sense of smell, so I probably wouldn’t smell much), but it’s fun to think about it when I go birding. What do American Avocets smell like?

I have also never wondered whether birds carry a distinct odor and whether they can distinguish amongst other creatures’ odors. But Danielle Whittaker has. In The Secret Perfume of Birds: Uncovering the Science of Avian Scent she describes how she came to avian olfactory research by an interest in researching mate choice of birds and had an idea that smell might be involved. Whittaker had not yet gotten the message that birds don’t smell, her intellectual background was in primate research, but a colleague set her straight, telling her, “Birds don’t have a sense of smell, so I don’t understand why you’d study that anyway?” (p. 1). It’s a great opening to the book, setting up the two themes–the research itself and Whittaker’s personal struggle to establish an academic scientific career outside the usual, expected path of tenure track and traditional intellectual boundaries. Written with humor, curiosity, and a lot of warmth, The Secret Perfume of Birds is an unexpectedly good read. Challenging at times, especially for us nonscientists, but Whittaker very smartly combines explanations of scientific concepts and processes with her own thoughts and feelings about the work, the intellectual history that preceded it, and the people she works with. There’s also roller derby stuff

Going back to that assumption that birds don’t have a sense of smell, it can be traced to John James Audubon (of course), who performed several experiments with Turkey Vultures and concluded that the vultures used sight, not scent, to find food. Audubon’s methodology has since been roundly critiqued (and it’s also suspected that he experimented with Black Vultures, not Turkey Vultures) and we now know that Turkey Vultures have a superior sense of smell. Also tubenoses and Kiwis can smell very well. Actually, many birds are able to use smell; the 2006 edition of the classic textbook Ornithology states, “Although they have been underestimated in the past, the olfactory abilities of most birds are comparable to those of some mammals (Mason and Clark 2000). Birds use the sense of smell in a variety of activities ranging from finding food to orientation….The small size of the olfactory bulbs in most birds (relative to brain size) fostered the belief that only a few exceptional birds—those with large olfactory bulbs, namely, vultures, kiwis, and petrels—use the sense of smell.” * Nevertheless, the myth continued. Whitaker was told that birds don’t smell by a in 2008.

Whittaker started asking questions beyond “do birds have a sense of smell?” such as “how do birds smell? (some, apparently, like sugar cookies), and “how do they communicate information by their odors?” And she started looking at and analyzing preen oil. You know preen oil, it’s the oleaginous substance birds secrete to coat their feathers and keep them neat and free of parasites. It also, it turns out, contains ‘volatile compounds’ (“small chemical compounds that have a tendency to vaporize at room temperature”, p. 241) that contribute to a bird’s odor. One of Whittaker’s first experiments was to place other birds’ preen oil on the nests and eggs of Dark-eyed Juncos. The Juncos reacted to alien scents, even temporarily reducing the time spent on the nest. She also found other research on birds and smell, particularly the pioneering work of Bernice Wenzel, the medical illustrations of Betsy Bang, Gabrielle Nevitt work with seabirds, and more recently, the Crested Auklet studies of Julie Hagelin and the genetic olfactory research of Silke Steiger in Germany. It’s not clear why so many researchers in this field are women (there are many more currently doing research in avian chemical ecology and Whittaker estimates that the gender divide in the field is about 50-50), but it may be one reason why the myth that birds don’t smell has not been knocked off its pedestal until now. It’s taken a critical mass of women scientists to be heard and to be respected. Whittaker muses about changes in the status of women in science and the need for more change (as in biases in research) in one of her final chapters, “Girl Power,” and it’s one of my favorite chapters in the book.

Author Danielle Whittaker, © Nicole Cottam

Whittaker’s research road is more serpentine than most academics. Her doctorate is in biological anthropology, her doctorate on the evolutionary genetics of Kloss’s Gibbons; she comes to birds through a desire for something different and her postdoc job as manager of the Ketterson Laboratory (the laboratory of Dr. Ellen Ketterson–yes, another woman scientist) at Indiana University, a lab known for its long-term research on Dark-eyed Juncos. At every juncture she needs to learn concepts and procedures in totally new fields–bird anatomy, bird evolution, genetics, chemistry! (Did you know how much chemistry is involved in olfactory research? Well, I guess that makes sense when you think about it, smells are made up of organic compounds.) Whittaker’s talent is in allowing us to learn with her. She writes about science with clarity and humor, setting forth research as a series of questions that begets more questions and brings rewards in the richness of diverse collaborations and intellectual challenges, sometimes in the field, sometimes in the laboratory.

Her career path decisions are almost startling in their honesty; this is an area that is seldom, at least to my knowledge, written about formally, beyond Twitter threads and the occasional Chronicle of Higher Education article. Her multiple rejections from tenure-track positions and the mixed messages she gets from the few departments that invite her for interviews will resonate with most any academic job seeker (though I need to say that as a former academic librarian I did not see “misery” all around me, just occasionally). Whittaker has creatively carved out “alternate” career path, managing scientific communities–first the Ketterson Lab, now science centers–utilizing an obvious talent for administration. About midway through The Secret Perfume of Birds she enthusiastically describes taking on the challenge of becoming managing director of the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action at Michigan State University, a Science and Technology Center funded by the National Science Foundation. Whittaker continued her research at BEACON, working with evolutionary biologist Kevin Theis on the groundbreaking idea that the odorous compounds in preen oil are produced by bacteria in the uropygial gland, and also trying to do some gene sequencing in an unsuccessful effort to understand the role, if any, played by MHC, the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC). I was startled to find out a few days ago that she is now managing director of COLDEX, the Center for Oldest Ice Exploration at Oregon State University, another NSF Science and Technology Center. Certainly a strange choice for an evolutionary biologist. Or is it? Danielle Whittaker’s The Secret Perfume of Birds is really about the triumph of unconventional choices and the knowledge gained from creative, out-of-the-box thinking. I’m looking forward to her next book, where I hope she somehow combines Antarctic exploration with avian olfactory behavior. With a little bit of ice adventure thrown in for fun.

Some additional thoughts:

- To help us non-scientists, the book includes a 9-page Glossary of terms like “Allele,” “Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC),”and the all-important “uropygial gland.” Terms in the text are italicized to indicate they are in the Glossary and the definitions are in plain language. This is an extremely helpful aid. Even though most of these terms, maybe all, are also explained within the text, I found myself looking them up in the back the next time they were used.

- There is no bibliography, a References section lists articles by chapter, in the order in which they are discussed in the text. I appreciate the fact that there are references (some popular science books don’t bother) and I understand why JHU might not want to insert the many numbers that would be necessary for orderly citations, but it is not easy to find an article. A bibliography would be much more efficient.

- Hooray, an index! I have my quibbles (Brown-headed Cowbird should be under ‘Cowbird, Brown-headed,’ not ‘Brown-headed Cowbird’) but it’s pretty good, indexing names, birds, animals, and scientific topics.

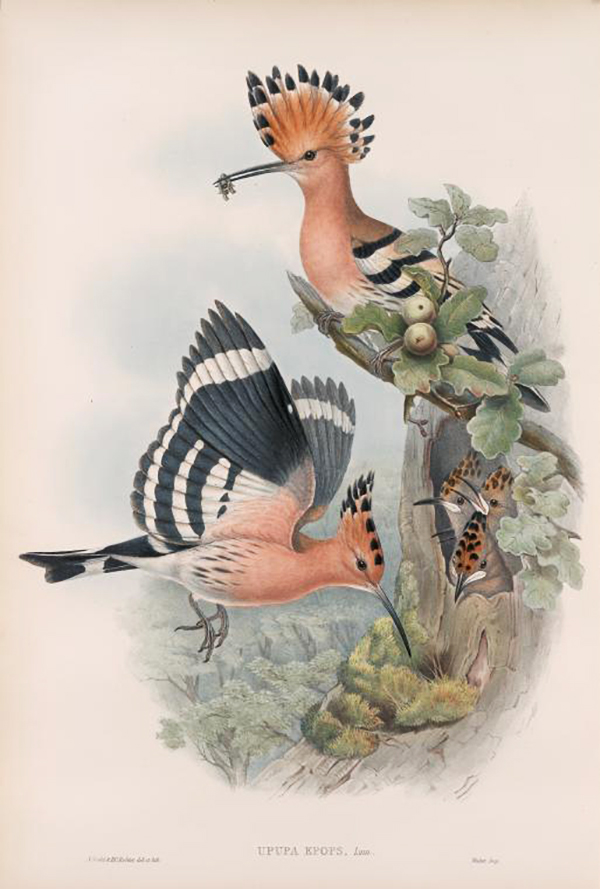

- I love the cover design by Amanda Weiss, featuring two Eurasian Hoopoes, female and male, taken from John Gould’s The Birds of Great Britain (1862-1873). It is also a bit misleading. Hoopoes do come up in the chapter on bacteria–Whittaker cites a series of “important” research studies out of Spain that she and co-investigator Kevin Theis find insightful and inspiring. But the real avian star of the book is the Dark-eyed Junco, the subject Whittaker uses in many of her research projects, the almost-victims of bear predation in the dramatic “bear in the aviary” story in chapter 3, the bird whose uropygial gland adorns chapter 2, the only illustration of this key anatomical part that is the source of birds’ odor. Why not a book cover featuring Dark-eyed Juncos? Not as “sexy” as Hoopoes, perhaps, but quietly beautiful (especially the Red-back subspecies) and really what Whittaker’s research is all about.

Hoopoes by John Gould, The Birds of Great Britain, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-birds-of-great-britain#/

* Gill, Frank B. & W. H. Freeman, Ornithology, 3rd edition, W.H. Freeman, 2006, full text available on Internet Archives, https://bit.ly/3bmSNJ8

The Secret Perfume of Birds: Uncovering the Science of Avian Scent by Danielle J. Whittaker

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022, 296 pages

ISBN-10 ? : ? 1421443473; ISBN-13 ? : ? 978-1421443478

$27.95, hardcover; available also in ebook, Kindle, and audiobook formats.

Leave a Comment