In the most of Europe, Brown Bear is a mythical creature that lives only in mediaeval tapestries and folk tales. It has become extinct, one may say, but such formulation hides the gruesome fact: it has been exterminated. By us.

About a quarter of the world’s Brown Bears live in Europe (including the Russian part of it), some 55,000, divided into nine separate and evermore fragmented populations – some of them dangerously tiny, a dozen or two dozen animals only. In the European Union there are only 10,000 mature bears (source: IUCN).

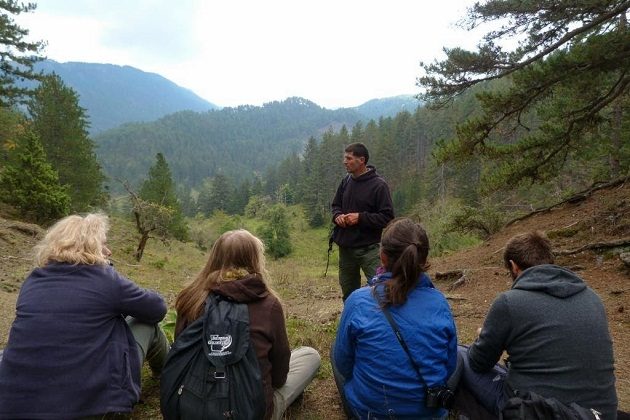

This September I found myself on a bear tracking tour organised by Natural Greece in the prime bear habitat of the Pindos range – the southernmost bear country in Europe, heading for the 2,520 m / 8,270 ft high Gramos Mountain along the border with Albania. Draped in dense forests of black pine, beech, fir, spruce and Scot’s pine, this is one of the least populated areas of Greece, with merely 0.47 inhabitants per km², mainly livestock farmers.

At the edge of the forest, above the road, a Roe Deer swiftly disappears between trees. Not much further, on the new tarmac that ends 6 km before the Gramos village, we find muddy bear footprints crossing the road. Up to 100 kg – possibly a female, my guide and a bear researcher from the wildlife charity Callisto, Yannis Tsanakis, tells me. Adult male bears in Greece usually weight about 150 kg and up to 200 kg, he explains further. At the same time, a Peregrine Falcon flies across the valley.

While the Scandinavian and European Russian population of bears is estimated to about 38,000 animals, the remaining populations are few and far between in the Iberian (15 + 200 ind.) and Apennine peninsulas (30 + 50 ind.). Only the Balkan (700 + 2,500 ind.) and Carpathian populations (8,000 ind.) combined offer a larger range as well as a larger gene pool (source: Euronatur). And I am inside the southern tip of the western Balkan Dinara-Pindos population range, stretching from Slovenia in the north to Greece in the south, with 2,500 bears.

After filling our water bottles at the clear mountain spring, the group splits and the majority continue on foot across the high pass to find many signs of bear presence in the area – scratching posts, scat (above), footprints; while the two of us continue by car along the very good final section of macadam prior to the village.

One Robin hides among the coppery-red foliage. Further, underneath the some 100 m / 330 ft high limestone cliff, there is a sort of an oasis with a water well and several fruiting trees. Goldfinches feed on the thistle seeds, a Common Chiffchaff hides among the yellow leaves, quite a few Chaffinches are flushed by a Eurasian Sparrowhawk attack… Could it be that the south facing cliff reflects some sunlight back and creates a warmer microclimate in the vicinity?

Over the pass, trees turn to pines – one very dark Eurasian Red Squirrel in them – and peaks around us become much higher. A Willow Tit feeds on thistle by the side of the road. Further into extensive mountain pastureland and cliffs, flocks of young Serins fill the trees, while the warmth-loving Cirl Buntings of lower elevations are now replaced by the sturdier Yellowhammers.

The slopes widen in front of us, forming a valley with perhaps 20 stone houses of the village of Gramos, at 1450 m / 4,760 a.s.l. – the highest in the country. Hard to imagine nowadays, this majestic mountain setting was a major communist guerilla stronghold in the Greek Civil War (1946-1949) and the region is scarred by the events and the memories of them. Even 70 years later, the elders still do not like to talk about it. By the last year of the war, the US increased its military aid to the Greek Government and introduced a new weapon: the first napalm attack after World War II took place right here! Like many others, this village was totally abandoned and only recently repopulated, with a current population of only 18 people.

By the riverbank at the edge of the village, willow bushes are full of Serins with an addition of several Linnets, while the sky is filled with migrating Common House Martins and a several Common Ravens.

In late afternoon when most of us were chatting by the fireplace in the log-cabin Gramos Lodge, Tsanakis climbed a low hill wedging itself into the village, to find it full of bear tracks and scat. Callisto studies of bear diet prove that about 90% of their food in Greece is plants, mostly fleshy and dry fruits. According to the latest research data, the total Brown Bear population in Greece is 475 to 500 and here in the Pindos range there are 350 to 400 animals (Pilidis, 2015, in pub.).

About ten years ago, when EU funds for such endeavours were available, the Callisto charity proposed to local government to push for the creation of the Gramos national park. Afraid that their ideas for the development of the area, including a ski centre, might be restricted by the nature protection regime, the officials rejected the idea. Only recently they told the Calisto that it might have been a good move, but with the advent of the crisis, both in EU and Greece, there is no money for it anymore. Still, some sensible ecotourism might bring a positive change to the lives of the people who are proud to have bears as their first neighbours.

In the end, have I seen my bear? Although one member of the group spotted a mother with two cubs, I have not. Am I disappointed because of that? Not at all. I saw so much proof of the presence of this apex predator and spent several days up and down some of the finest bear country in Europe, well knowing that if bears live in these forests, all lower links of the food chain and the intricate tapestry of the ecosystem is here as well. After all, bears are solitary and elusive animals. And I came here to track them. No, I haven’t seen my bear, but I do feel fulfilled nevertheless. While searching for bears, I may have found a piece of myself.

Photos (c) Maria Petridou

Practicalities

The tour was organised by the Natural Greece ecotourism specialists from Athens, Greece, in collaboration with the Callisto wildlife charity which has done a lot of work on bears in this area. One of their more noticeable achievements is lowering accidental bear mortality several times, from 9 in 2009 when the new motorway was constructed – through changing 130 km of inadequate fences with higher bear-proof ones and erection of 6,000 wildlife reflectors, plus two dozen warning signs for drivers – to 2 in 2015 and zero in this year.

The tour starts in Greece’s second largest city – Thessaloniki, serviced by EasyJet, Ryanair, British Airways and the Aegean Airlines, among others. Our guides were researchers from Callisto, patient and always smiling Yannis Tsanakis (above) and Maria Petridou with her infectious laugh and stories of her Sun Bear and Jaguar research experiences. The bear walks are relatively easy and, while possible in sneakers, some light ankle-support hiking shoes might be preferable. Also, trekking poles proved useful.

The cuisine was magnificent, especially lamb. At one occasion, during the hike Tsanakis collected wild mushrooms and in a restaurant, asked the chef to prepare those for us. Finally, Greeks do have some magic potion called tsipouro, very worth trying.

Further reading: Central and Eastern European Wildlife by Gerard Gorman (Bradt Travel Guides)

My tour list (late September… also, birders were a minority within a group):

1. Mute Swan – Cygnus olor

2. Great Crested Grebe – Podiceps cristatus

3. Pygmy Cormorant – Microcarbo pygmeus

4. Dalmatian Pelican – Pelecanus crispus

5. Short-toed Snake-Eagle – Circaetus gallicus

6. Eurasian Sparrowhawk – Accipiter nisus

7. Common Buzzard – Buteo buteo

8. Eurasian Coot – Fulica atra

9. Black-headed Gull – Chroicocephalus ridibundus

10. Feral Pigeon – Columba livia dom.

11. Eurasian Collared-Dove – Streptopelia decaocto

12. Eurasian Nightjar – Caprimulgus europaeus

13. Pallid Swift – Apus pallidus

14. Great Spotted Woodpecker – Dendrocopos major

15. Eurasian Green Woodpecker – Picus viridis

16. Common Kestrel – Falco tinnunculus

17. Peregrine Falcon – Falco peregrinus

18. Woodchat Shrike – Lanius senator

19. Eurasian Golden Oriole – Oriolus oriolus

20. Eurasian Jay – Garrulus glandarius

21. Common Magpie – Pica pica

22. Eurasian Jackdaw – Corvus monedula

23. Hooded Crow – Corvus cornix

24. Common Raven – Corvus corax

25. Woodlark – Lullula arborea

26. Crested Lark – Galerida cristata

27. Barn Swallow – Hirundo rustica

28. Red-rumped Swallow – Cecropis daurica

29. Common House-Martin – Delichon urbicum

30. Sombre Tit – Poecile lugubris

31. Willow Tit – Poecile montanus

32. Blue Tit – Cyanistes caeruleus

33. Great Tit – Parus major

34. Long-tailed Tit – Aegithalos caudatus

35. Eurasian Nuthatch – Sitta europaea

36. Common Chiffchaff – Phylloscopus collybita

37. Eurasian Blackcap – Sylvia atricapilla

38. Spotted Flycatcher – Muscicapa striata

39. Robin – Erithacus rubecula

40. Blackbird – Turdus merula

41. Starling – Sturnus vulgaris

42. Grey Wagtail – Motacilla cinerea

43. White Wagtail – Motacilla alba

44. Tawny Pipit – Anthus campestris

45. Tree Pipit – Anthus trivialis

46. Yellowhammer – Emberiza citrinella

47. Cirl Bunting – Emberiza cirlus

48. Chaffinch – Fringilla coelebs

49. Goldfinch – Carduelis carduelis

50. Linnet – Carduelis cannabina

51. Serin – Serinus serinus

52. House Sparrow – Passer domesticus

53. Tree Sparrow – Passer montanus

Thank you Dragan for describing our trip (oct 3-7)as well. We did not spot a bear either – but, in the end, that was of no consequence. The gorgeous mountains, the warmth and friendliness of the people we met, the serious and dignified working shepherd dogs, our patient and professional guides, the new-found knowledge of bear tracking we gained, and the sheer pleasure of being ‘lost’ in the outdoor and ancient wild spaces of Northern Greece all more than compensated for not actually seeing a bear. They were everywhere though unseen – and were kind enough to allow us to tramp noisily through their home.

Seeing vs. chasing – I am beginning to think about the line I heard in some b-movie the other evening, “he is not that much into finding as in the thrill of the chase.”