Lili Taylor knows how to look and how to listen. As an actress, she’s been trained to use these skills to give outstanding, grounded performances on film, television, and stage. In Turning to Birds: The Power and Beauty of Noticing, she writes about how she’s applied these and other actorly skills to learning to know the birds around her, whether she’s on the job in New Mexico, a newbie at a large birding festival, or simply walking in her neighborhood in Brooklyn. But that’s not all. Like any good essayist, Taylor effortlessly connects the personal to the universal, in this case going from bird observation to major conservation issues.

In these thirteen essays, Taylor writes with immediacy about how she became aware of birds during “an emotional sabbatical” at her house in upstate New York; her first slightly apprehensive visit to a birding festival (the Biggest Week in American Birding festival in Ohio); the myriad colors one sees when observing a Blue Jay through good binoculars; and figuring out the mysteries of desert birding while on location in Albuquerque, New Mexico. There are essays about two Cedar Waxwing experiences, one in person, one via a bird tattoo competition; the wonders of chimney swift roosts and the importance of documenting them; the experience of monitoring birds trapped in the 9/11 Tribute in Light under the auspices of the NYC Bird Alliance; creating an environment for House Finches on a bare studio lot in Santa Fe, New Mexico: and tracking the nesting of Catbirds in Bryant Park on the way to work (in this case, from the subway to the Broadway theater where Taylor is performing). There is a masterful reworking of an essay that appeared in the collection Good Birders Still Don’t Wear White (2017) about fighting House Sparrows trying to take over Bluebird nest boxes on Taylor’s upstate property; the magic of watching Sandhill Cranes leaving and returning to their Platte River roost at the Audubon Rowe Sanctuary; observing Woodcocks peent and dance in Brooklyn and in Ohio (where strangely, she’s encouraged to lie at the spot where the Woodcock has just taken off from so it lands on her chest–is that a thing in Ohio?); and finally, the ecstasy of observing spring migration at night from the top of the Empire State Building (I had no idea this was possible, but it is, doors close at 10:45pm the first two weeks of May, though ticket prices rival those of the back row of a Broadway show).

Certain motifs run through these essays, reflecting Taylor’s approach to birding, acting, and life. She loves coffee cafes, and her personal heaven is combining birding with a visit to a really good coffee place. This is her ‘Bedouin rug,’ she writes, where there are birds and coffee, she is home. She is an avid user of apps, and we see her using not just eBird, Merlin (“the equivalent of Shazam for birds”), and iNaturalist, but also BirdsEye, BirdCast, Sibley’s, and a new one for me, mynoise.net, which creates soundscapes (this fee-based app doesn’t seem to have a lot of nature soundscapes–Taylor uses it to create a coffee cafe ambiance–but it was created by Stéphane Pigeon!). Taylor’s mind is deeply curious. She’s constantly figuring stuff out, whether it be how to locate a skulking Catbird in a crowded urban park or how to build a birdhouse for finches out of hardware store parts, and connecting her questions about the birding process to what she’s read and learned in the past. Taylor’s use of acting techniques to help her be a better birder makes this book unique. She makes a list of the skills shared by actors and birders: Listening, attention, investigation, observation, perception, specificity. She discusses each within a framework of teachings by acting gurus and naturalists (E. O. Wilson is a favorite), but not for long. Taylor’s mind is quick and her voice is honest, and she knows we are here for the stories.

If you’re not familiar with Lili Taylor’s acting work, think of the films Mystic Pizza, Household Saints, I Shot Andy Warhol, The Haunting; of television series American Crime, Six Feet Under, Outer Range, Almost Human–there are 93 acting credits on IMDB! In the theater, she’s appeared in Broadway and off-Broadway plays, including The Three Sisters (which I was fortunate to see), Marvin’s Room, Mourning Becomes Electra, The Library, and The Fever, a one-person play which plays a small role in the book.) Taylor is very conscious that being an actress of note gives her a special position in the birding world. In the chapter “Bins,” she tells Swarovski representative Clay Taylor (I don’t think there’s a relationship there), “I’m not that kind of celebrity–I’m more of a working actor whom some people know…” But enough people know her that she has become an effective representative for birds and conservation: a board member of the National Audubon Society and NYC Bird Alliance, past board member of the American Birding Association; the featured face and voice in articles and social media videos about the Lights Out for Birds program, the Audubon Rowe Sanctuary in Nebraska; an advocate for developing native plant gardens and for urban birding in general.

Taylor’s writing is too elegant for outright pontification, she lets the stories carry the message. She builds bluebird boxes so the Eastern Bluebirds on her upstate property can nest, and finds out there is a larger story, that bluebird populations are declining because of degraded habitat. She seeks out school chimneys with her mother to watch Chimney Swifts circle in to roost, but the next year the school chimney is blocked and then removed, and she discovers that this is happening all over the country, and that scattered community science projects are collecting data and monitoring roosts in efforts to support swift conservation projects. Even the essay on the 9/11 Tribute in Light, the essay most clearly focused on conservation and one of my favorites for its New York City connection, is grounded in personal observation and discovery–Taylor’s stumbling efforts to find the birders on the garage rooftop where they do the monitoring (I loved that part because I would be lost too), her confusion when she lies on her back and tries to figure out how to count the birds in the light beams, the suspense when Susan, the scientist in charge, goes to negotiate with the Tribute in Light people, dead warbler in hand, over shutting down the lights for 20 minutes. Taylor has started the chapter with the scientific explanation of why we think migrating birds are killed by city lights and the statistics, but it is those two hours on the rooftop, observing “the infinite light edged by black, filled with what look like energetic, infinistesimal life forms” that make the point.

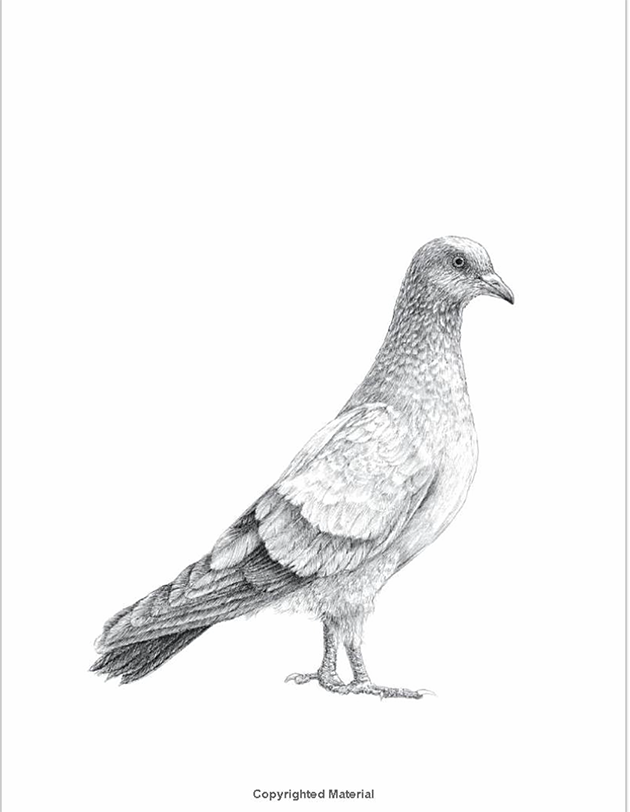

© copyright 2025 by Lili Taylor & Penguin Random House LLC, page 2

Essay chapters are illustrated with lovely, finely tuned black-and-white bird drawings by Anna Koska, an experienced book illustrator. I particularly like the final illustration for Chapter 13, a migrating fantasy of a Sandhill Crane, Cedar Waxwing, American Woodcock, Gambel’s Quail, House Finch, and other birds written about in previous chapters, all migrating together, presumably over the Empire State Building. The cover painting of a Catbird on Virginia Creeper is taken from an illustration by Isaac Sprague, a 19th-century naturalist and artist, and if it looks vaguely Audubon-ish, it’s probably because Sprague assisted John James on an expedition up the Missouri River and, according to Wikipedia, some of his drawings were later used by Audubon in his publications without credit. Interestingly, Black-headed Cuckoo-Shrike is used as the cover bird for the U.K. edition published by PanMacmillan, taken from a water color by 19th-20th century British artist and amateur ornithologist Margaret Bushby Lascelles Cockburn.

One nitpick that I hope will be corrected in future editions of Turning to Birds: Taylor mentions observing watching two Anna’s Hummingbirds in the fall at Brooklyn Bridge Park in the chapter “Woodcock.” Though there are a handful of records of this western hummingbird appearing in New York State, there is no record for Brooklyn. I can only imagine this is an editorial oversight and that Taylor meant Ruby-throated Hummingbird. I originally detailed a second nitpick concerning Cooper’s Hawks being labelled part of the Accipiter genus in the chapter “Bins.” Cooper Hawks are now part of the new genus Astur, a 2024 change too recent to have made it into the book. However, as is common in the confusing ways of taxonomy, the change has not been confirmed in all taxonomic systems. While it is listed as Astur cooperii in eBird and its companion taxonomic system, Clements, and listed as Astur (Accipiter) cooperii in the American Birding Association’s most recent Checklist, it is still Accipiter cooperii in the American Ornithological Association taxonomy. So, I take the nitpick back! (Note that the AOS has proposed this change in this year’s proposals, so it is likely Cooper’s Hawks will soon belong to the genus Astur everywhere.)

Turning to Birds: The Power and Beauty of Noticing by Lili Taylor is clearly written for people new to birds and birding, offering both structure for consciously appreciating birds, inspiration, and insights into the places and things that distinguish the birding world, from apps to festivals to citizen science. I think it also has a lot to offer the more experienced birder. Taylor’s approach to birding, rooted in her acting background and mobile life, is unique, her conversational writing style engaging, and her wonder infectious. Reading this book may remind some of us why birding is our passion.

Turning to Birds: The Power and Beauty of Noticing

by Lili Taylor

Crown, April 2025; Pan Macmillan (UK), May 2025

208 pages; hardcover (also available as Kindle and audiobook), $30.00

ISBN-10 : 0593728572; ISBN-13 : 978-0593728574

Another great review Donna. Thank you. Knowing that the book is an essay collection, I look forward to checking it out. Sometimes essayists insights are very personal and, in the case of birding, not always so easy to connect with. Although in this author’s case it seems she may also use NYC as a back-drop (pun not intended). So this might also make NYC a character in her essays. Thank you also for reminding me of the new genus for Cooper’s Hawk – Astur. I have not yet purchased an updated field guide and I always forget to go on-line to check out these important details. Prior to reading your review I had never heard of Lily Taylor. I feel better knowing who she is.

Thank you very much, Cathy! I appreciate your comment about not knowing who Lili Taylor is, since I was on the fence about including so much bio info. She’s one of those actors who can slip into a role completely. I agree with your comments about essays. In this case, I felt like the author was using personal experience to present more general insights to the reader rather than staying in the personal realm. It’s a contrast to another collection I enjoyed, Field Notes from an Unintentional Birder: A Memoir, by Julia Zarankin (which I reviewed for Birding magazine).