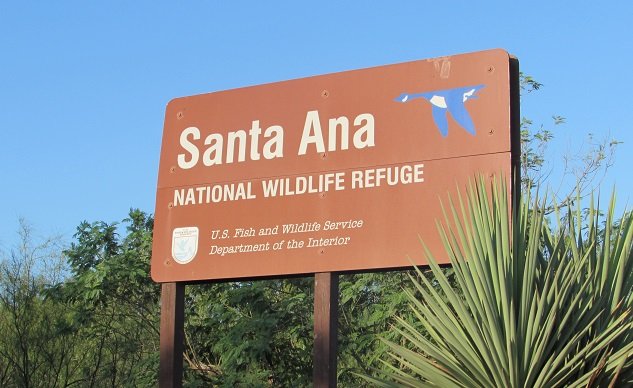

When the news broke about a possible border wall through Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge in Texas, I decided to make plans to visit before it got bisected by a concrete barrier.

I have been to refuges across the United States, but I never thought that I would have a deadline to visit any particular refuge. After all, each refuge has been set aside to permanently protect birds and other wildlife. Indeed, The U.S. Fish and wildlife Service has a legal mandate to manage national wildlife refuges for “the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.” But in the current political climate, even permanent environmental protections can prove transitory.

Getting from Portland, Oregon to McAllen, Texas—one of the towns near Santa Ana NWR—is neither quick nor easy, but I arrived on Sunday, November 5, 2017. The visitor center is a nondescript building, but it is staffed by friendly volunteers and they provided advice and a map, so off I went. It was hot and most of the ponds and wetlands were dry. Nevertheless, if you have not spent much time birding in the area, it is difficult not to find lifers. I added: Great Kiskadee, Harris’s Hawk, Green Jay, Plain Chachalaca, and Least Grebe.

I hopped on the tram tour and learned about the ecology and some of the history of the refuge, which was established in 1943. It is small—just 2,088 acres—but it includes some of the last remnants of the scrub habitat that once covered much of Texas. Just 5% of that habitat remains: 95% has been converted to urban development or agriculture. The refuge is an island of relatively intact native habitat surrounded by an ocean of development. (This can be clearly seen on Google Maps.)

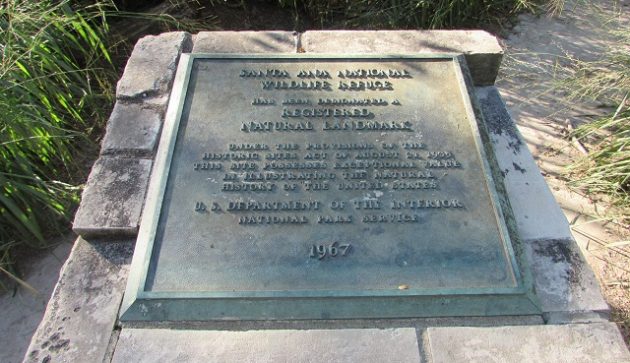

I walked along a number of trials and visited the observation towers. Near the towers is a marker indicating that the refuge is registered as a National Natural Landmark. There were numerous reminders that the refuge is on the U.S.-Mexico border. Green and white Border Patrol trucks rumble by and armed officers patrol the area. Several trails wind along the banks of Rio Grande, which constitutes the border between the United States and Mexico. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service signs, usually in English, are also in Spanish.

Of course, this proximity to Mexico now threatens the refuge.

A key part of Donald J. Trump’s presidential campaign was his promise to build a “great wall” along the border with Mexico. So far, that promise has gone nowhere and the assurance that Mexico would pay for it is long gone. But the Administration is pushing hard to prove that it can deliver on promises made on the campaign trail. To date, Congress has refused to provide funding for construction of a wall, though it may do so later this year. However, prototypes have been built.

The wall cannot be built on the actual border, which is the Rio Grande river, as the floodplain is technically protected by a treaty between the United States and Mexico. Moreover, the river is dynamic and has changed its course over time, which presents engineering and construction challenges. So the wall must be built away from the actual border, which means that part of the the United States will be on the “other” side of the wall.

Much of the land along the border is privately owned and the federal government cannot simply build on private property without permission. If permission is denied, the government must use the legal power of eminent domain to obtain the land. That can take years, particularly in Texas, where property rights are deemed sacrosanct. Protracted and expensive litigation is often required.

However, eminent domain is unnecessary where the federal government already owns the land. Thus, the fact that the government acquired the land to protect migratory birds is partially responsible for the possibly of a wall that would likely harm migratory birds. It is bitterly ironic that setting aside the refuge for conservation makes it uniquely vulnerable as a site for a border wall.

The prospect of a wall is especially disheartening because there is no compelling case for it and there appear to be other alternatives that may be just as good or even better. But alternatives are being largely being ignored and laws that would require consideration of other options will be simply be waived.

If this were a logical fact-driven policy process, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) would gather all of the relevant evidence and weigh the costs and benefits. Some of those considerations would include whether border walls are effective in the first place. After all, there are more than 600 miles of border fencing, walls, and other barriers in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and there has been plenty of time to assess the effectiveness of barriers.

An analysis would include an assessment of whether a wall would be the most efficient form of border control in a particular area, compared to other alternatives. It would also consider cost, design, location, and other variables, such as the impact on the environment, including endangered species.

For example, would building and maintaining and staffing a 30-foot concrete wall be more effective than hiring more border patrol agents and/or incorporating technology, such as cameras, radar, sensors, and/or drone surveillance? (This article by the Border Patrol identifies some of the technologies used in Arizona and this New York Times article looks at technology used in Texas.)

But such an analysis can barely be conducted because the Border Patrol has, remarkably, no reliable analysis of the effectiveness of border walls. A General Accounting Office (GAO) study in 2017 determined that the Border Patrol has not yet developed metrics to determine whether its existing barriers are effective. GAO wrote:

However, CBP has not developed metrics… to assess the contributions of border fencing to its mission…. Developing metrics to assess the contributions of fencing to border security operations could better position CBP to make resource allocation decisions with the best information available to inform competing mission priorities and investments.

And it recommended:

GAO recommends that Border Patrol develop metrics to assess the contributions of pedestrian and vehicle fencing to border security along the southwest border and develop guidance for its process for identifying, funding, and deploying TI assets for border security operations. DHS concurred with the recommendations.

Thus, an intelligent analysis cannot even occur because there are simply not enough facts. It is virtually impossible to assess what combination, if any, of barrier, technology, and personnel, is best-suited to any particular location, particularly when locations can be urban or rural, mountainous or flat, environmentally sensitive or not, and so forth. No credible analysis of a proposed wall at Santa Ana NWR has been made public.

Significantly, none of the environmental laws that might normally apply to development decisions by the federal government will apply to construction of a wall. Congress has empowered the Secretary of Homeland Security to waive all federal, state, or local laws when it comes to building barriers along the southern border.

For example, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), is designed to insure that federal agencies give proper consideration to the environment before undertaking any major action that significantly affects the environment. NEPA typically involves and environmental impact statement that sets forth the purpose of the project, its potential environmental impact, and considers various alternatives to achieve the purposes. But if funding for a wall is approved, DHS will simply waive NEPA and all other environmental laws, as it has in the past. As a result, environmental considerations and alternatives will essentially be ignored.

It is possible, even likely, that building a wall would not be the most effective method of addressing border issues near Santa Ana. The Americans most impacted by immigration issues—Texas border communities— are generally opposed to more barriers, as are many other Texans. These are the people who would most directly bear the burdens and reap the benefits of a wall, so their views are worthy of consideration.

If there were credible facts to analyze, one might be able to look at the costs and benefits and come to same rational conclusion about whether Santa Ana NWR is a sensible place to build a wall, and if so, what kind of wall and where. But a serious analysis hasn’t been done and there’s no indication it would ever be done before construction. The true goal appears to be to build a section of wall so President Trump can point to it and claim he is delivering on one of his major campaign promises, regardless of its effectiveness or the views of local communities. The wall appears to be no more than a symbol.

For a birder—or anyone interested in the environment—that is a poor justification for potentially destroying one of the treasures of the national wildlife refuge system.

Photos of Santa Ana NWR and Harris’s Hawk by Jason Crotty.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

” each refuge has been set aside to permanently protect birds and other wildlife.”

This is a FALSE statement. Some NWRs are LEASED from other entities and the leases are not guaranteed to be renewed.

For example, Santee NWR in South Carolina is leased from the Santee Cooper authority, a quasi-public public utility. The lease is up in 8 years and Santee Cooper to date has not responded to USFWS inquiries regarding lease renewal.

Also in SC, Cape Romain NWR is leased from SC DNR. Ongoing renewal of the lease is not viewed as being in jeopardy but it is not guaranteed.

But in this case, FWS owns the land in fee simple and the land was specifically acquired to protect migratory birds. There are some nuances if you consider the entire system but they don’t appear to apply here.

My husband and have just driven down from Dallas on Saturday and are staying in South Padre Island. The purpose of our trip is birding, the hobby which i have returned to voraciously after more than 30 years.

This past weekend was particularly heartbreaking as Kavanaugh was sworn in to the Supreme Court. We believe he will help to rubberstamp all of the destructive mandates of this illegitimate autocratic administration, with the dismantling of evironmental protections and the destruction ofhistrically pristine habitats at the top of its list. My husband and I will try to visit as many Rio Grande Valley and coastal wildlife sanctuaries as we can this week. We are hoping we can actually see some of the birds on our life lists even through the tears in our eyes.