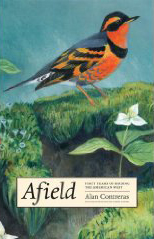

Alan Contreras is one of the deans of Oregon birding, having literally written the book (actually several) on the subject. I came across his latest offering, Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, when Amazon suggested it to me, so I put it on my wish list and was lucky enough to receive a copy this past Christmas. While reading the book I felt like I was transported to the west coast and it almost made me wish I had grown up in the varied terrain of the Pacific Northwest rather than in the Catskill Mountains and Hudson Valley of New York State. Regardless of where you grew up or where you do your birding, Afield is a marvelous book that I highly recommend. While reading it I was surprised to come across a familiar name, that of Hendrik Herlyn, who showed me around the Griefswald part of Germany when I visited a couple of years back. Encouraged by this tenuous connection I contacted Alan Contreras and asked for an interview, which he graciously agreed to. The following question and answer took place via email.

Alan Contreras is one of the deans of Oregon birding, having literally written the book (actually several) on the subject. I came across his latest offering, Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, when Amazon suggested it to me, so I put it on my wish list and was lucky enough to receive a copy this past Christmas. While reading the book I felt like I was transported to the west coast and it almost made me wish I had grown up in the varied terrain of the Pacific Northwest rather than in the Catskill Mountains and Hudson Valley of New York State. Regardless of where you grew up or where you do your birding, Afield is a marvelous book that I highly recommend. While reading it I was surprised to come across a familiar name, that of Hendrik Herlyn, who showed me around the Griefswald part of Germany when I visited a couple of years back. Encouraged by this tenuous connection I contacted Alan Contreras and asked for an interview, which he graciously agreed to. The following question and answer took place via email.

Corey: Alan, thanks for agreeing to do this interview. It was your book, Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, that led me to ask you for an interview. In your preface you say that the book “is not exactly a history, a personal memoir, or a birding adventure book, though it offers elements of all three.” What made you decide to write a book about your lifetime of experiences birding in the west?

Alan: The impetus was completely unrelated to birds: I read composer Ned Rorem’s autobiographical Knowing When To Stop and it occurred to me that I might venture on something similar. Rorem is much longer and much better, of course, but I enjoyed doing Afield.

Corey: You started birding at age eleven, with your new friend Sayre Greenfield, who would become a lifelong friend. It seems that the two of you had plenty of time to go out and about in the great outdoors and see what there was to see. Do you wonder if (or worry that) twenty-first century kids might be spending too much time playing video games or being bound by rigid schedules and therefore are not getting that connection with nature?

Alan: Oh yes, this is a big issue, which I discussed recently on my blog, The Oregon Review. This is one reason that I have always focused my energy as an adult birder on helping young people come to appreciate birding. I spend most of my birding energy with young birders.

Corey: You and Sayre edited your own mimeographed birding newsletter, The Meadowlark, as kids. Have any copies ever shown up?

Alan: I have never seen any, other than the sets that Sayre and I have in our closets! However, I am currently the editor of Oregon Birds and we are thinking of having a special publication that we hand out at the annual

meeting of Oregon Field Ornithologists. I am tempted to call it The Meadowlark and assign it the next number in sequence from the issues we produced in 1969.

Corey: You’ve spent your entire life in Oregon and even work for the state. Throughout your book it is clear that you love the varied landscapes, habitats, cities, and people of Oregon. Can you neatly sum up what makes Oregon a great place for a birder to spend his or her life?

Alan: I actually lived three years in Missouri, too, working in Jefferson City and enjoying the birds of the northern Ozarks and southern plains. That segment was removed from Afield because the published wanted a purely “western” offering. But on the day I returned to Oregon in October, 1991, the radio really did play “I’m singing in the rain” as I crossed the Snake River Bridge into Oregon.

Oregon has exceptional habitat variety in a relatively small geographic space. I can go from the outer coast through the interior valleys, over the Cascade passes and into the pine and sage desert country in a single day if I am so inclined. It is possible to see a greater variety of owls, waterfowl or woodpeckers in one day in Oregon than in any other state.

Also, the state has a lot of public land, a number of excellent wildlife refuges and easy access to most habitats.

Corey: Pelagic birding is not your cup of tea and you even go so far as to endorse “Solid Ground Pelagic Birding” in Afield. Could you explain the basic idea behind this radical method of seeing pelagic birds? And would you rather have stomach that doesn’t churn at the thought of getting on a boat or five more birds on your Oregon life list?

Alan: Birding is supposed to be fun, and if it isn’t fun I don’t do it. That’s why I have missed a few good birds here and will probably miss more. There are days when I just don’t feel like driving 300 miles to see a bird, and there are 365 days when I would rather not be on a boat. I am more committed to pleasure than to my list. No one cares whether I have a big list.

Corey: You’ve done breeding bird atlas work, big days, lazy feeder watching, and taken long journeys to other states and countries to see birds you wouldn’t see in Oregon. What is your favorite way to bird? If you could make a one week itinerary of the best birding what would it be?

Alan: The best way to bird is almost always walking, so the trick is to find places to walk through enough variety of habitat to see as many birds as you can. Certainly the best single site is Malheur National Wildlife Refuge HQ, but the walking there is round and round a circle and gets a little tedious.

A week that started on the Oregon coast, went southwest through the marshes and mountains of Oregon, California and Nevada and ended up in southeast Arizona would produce a splendid variety. I have done that once with my friend Jude Vickery and I’d like to do it again sometime.

Corey: In your book (and, I would assume, in your life) you are open about the fact that you are gay. Has homophobia ever reared its ugly head in the birding community or are birders generally open-minded folks (or some combination of the two)?

Alan: One of the initial reviewers of Afield was clearly so offended by the one sentence in the book in which the word “gay” appeared that he just about laid an egg. The people at OSU Press realized that he had a problem. Broadly speaking, the birding community is fairly well educated and therefore I see less dislike of gay people there than one might find in a random cross-section of people. However, there are some people, especially those over sixty, who are not comfortable with gay people. One of the reasons that I like birding with college-age birders is that younger generations, even those of my friends who are religious or otherwise conservative, don’t really care about gayness. It is largely a generational issue.

Corey: You are the author of several books on the birds of Oregon and the northwest. Can you briefly let our  readers know what books you wrote when and why they might be interested in getting them?

readers know what books you wrote when and why they might be interested in getting them?

Alan: The main ones are Northwest Birds in Winter (1996), Birds of Oregon (2003) on which I served as co-editor, Afield (2009) and the Handbook of Oregon Birds (2009). They are totally different one from the other. Birds of Oregon is a huge reference book. The Handbook is probably the most user-friendly and is easy

to read.

Corey: One of those books, the Handbook Of Oregon Birds: A Field Companion To Birds Of Oregon, was coauthored with Hendrik Herlyn, a birder who was kind enough to help me see lots of German birds on my one visit to Europe. Birding is like that, we all know each other one way or another. What is the birding community of Oregon like? Does it amaze you that watching birds has led you to so many valued relationships?

Alan: Hendrik and I have been friends for a long time. Oregon’s birding community is generally quite relaxed and friendly, with none of the snootiness that one occasionally finds. Birders are mostly friendly and helpful. When I made my first visit to Australia in December, 2009, a local birder took me around and showed me piles of birds. It turned out that he had visited Oregon two years ago and a friend of mine had shown him such exotica as American Bittern! So yes, it is like a huge tapestry.

Corey: Alan, I said I would keep the interview brief when I asked if you would be willing to answer some questions. So, rather than rattle off some more I’ll give you this opportunity to say whatever you want about anything. Any final thoughts?

Alan: When in doubt, stop staring at the computer and get out of the house for an hour. Even if you only see common birds, rejoice.

Corey: Amen to that! Thanks for the interview, Alan.

Geez, I never realized Hendrik was such a big fish in the Oregon pond! Nice!!

And he’s back in Oregon, too!

Funny he mentions Jude Vickery. Back when I was a kid birder in Missouri, Jude was the other kid birder to whom I would be compared. And the tapestry grows…

I hadn’t heard about him in years. Glad he’s still into it.

@Jochen: I know, right?

@Nate: The birding world is waaaaay too small…

Hendrik is indeed a sizable fish in the Oregon pond and was my co-author on the Handbook as well as serving on the Oregon Bird Records Committee from time to time. He currently lives in Corvallis.

Jude Vickery is still birding from his home in Wayland, Missouri, but family responsibilities limit his birding time.

@Alan:

I met Hendrik a couple of times when he was staying in Greifswald, although sadly my birding time (with him and in general) was very limited back then.

He always mentioned that he wanted to return to Oregon as soon as possible and I am very happy he managed – although his very good observations are being missed along the Baltic coast of Germany.

Next time you meet or talk to him, send him my best regards and happy birding trails,

Jochen Roeder

Corey, interesting interview! Thanks for taking the time to interview Alan. I must agree that the trip from Oregon south in to Arizona was quite the trip. I have many fond memories and a great birding list to show for our flight through the west. I would recommend a similar trip to anyone who has never been out west who can take the time to carefully plan their route to make the most of the time available.

Alan, Nate, I must say it’s a little odd to find a conversation about myself while randomly looking around!

—Jude Vickery

@Jude: Thanks! Glad you liked it. And, yeah, it must be weird to find this discussion of yourself. 10,000 Birds: where birders stalk each other in the comments… 🙂