Next Thursday is the American Thanksgiving holiday – which means it’s time to trot out that old legend concerning Benjamin Franklin’s opinions on two iconic American birds: The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) and the Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). As every American schoolchild knows, the story goes something like this: The Founding Father was a staunch advocate for the adoption of the gobbler as the national bird of the young nation, and bristled at the final selection of the Bald Eagle, a bird he regarded as a morally suspect creature, much disposed to dishonest scavenging for its sustenance – and a bit of a coward, to boot. Ever the moral perfectionist, Franklin argued that the turkey was a much more honorable and determined fowl, and suggested the bird – as an “original Native of America” – would make a decidedly more fitting avian mascot for the United States (seemingly implying – incorrectly – that the Bald Eagle is not an indigenous New World species).

Except that it didn’t really happen that way, exactly. While Franklin did document his judgment on both birds, his legendary appraisal was never expressed publicly, and the only evidence of his opinion on the matter is recorded in a private letter to his daughter Sarah in which he disapproves of the appearance of an eagle on the crest of the Society of the Cincinnati, a hereditary society founded by veteran officers of the American Revolution. Franklin’s opinions on the two birds in his letter are certainly consistent with the story, but there’s no truth to the myth that he proposed any sort of official role for the turkey in the national symbols of the United States.

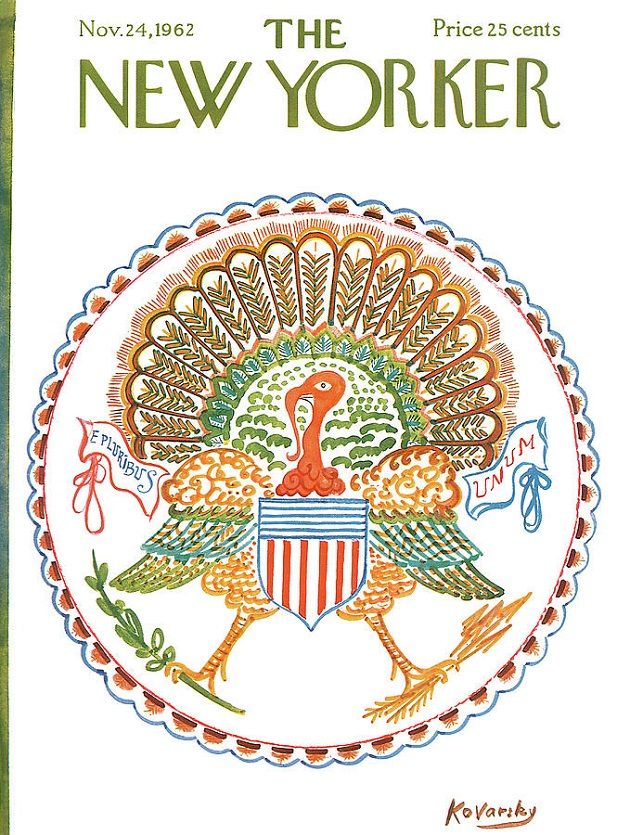

The November 1962 cover of The New Yorker by Anataole Kovarksy brought the fantasy of a turkey on the Great Seal of the United States – a myth wrongly attributed to Ben Franklin’s nonexistent public views on the matter – to life on the printed page.

In the interest of getting the story right and presenting Franklin’s original thoughts on the matter – complete with its colorful language and oddly moralizing tone – we offer the following excerpt from his letter:

Others object to the Bald Eagle, as looking too much like a Dindon. For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk [Osprey or Pandion halieatus]; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this injustice, he is never in good case but like those among men who live by sharping & robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank coward: The little King Bird [Eastern Kingbird or Tyrannus tyrannus] not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district. He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America who have driven all the King birds from our country…

I am on this account not displeased that the Figure is not known as a Bald Eagle, but looks more like a Turkey. For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America… He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.

Surely, Ben Franklin’s praise for the male turkey was also extended to the great mothering skills of the hen.

In the end of course, the eagle went on to become the national bird of the United States, despite the bad rap from old Ben. Today, Tom Turkey suffers a much less enviable fate every year, becoming the stuffed and roasted centerpiece of the Thanksgiving Day feast – though he’s the undisputed avian star of not just that day, but of the entire American holiday calendar. There’s no “Eagle Day”, is there?

However, in the spirit of fairness and inclusion in keeping with this holiday of gratitude, we’d like to make a place for the unfairly slandered eagle at the Turkey Day celebration at Birds and Booze. If you’re willing to forgive the flaws in its character discerned by Mr. Franklin, there’s an eagle on the label of our featured wine this week, an excellent red from Oregon whose flavors should accompany the unfortunate poultry on your table quite harmoniously – notwithstanding the great disparity in the moral temperament of these two birds alleged by the Founding Father.

According to Mr. Franklin, that catfish is undoubtedly ill-gotten gains, but there’s room at our Birds and Booze harvest festival table for even the most unscrupulous scavengers.

Unconditional is a 2017 pinot noir produced by Battle Creek Cellars of Turner, Oregon, which lies just south of the state capitol of Salem in the Willamette Valley wine country of Marion County. The county is perhaps most famous for an eponymous blackberry cultivar grown there, but the vineyards of Battle Creek are wholly devoted to grapes of the pinot noir variety, where winemaker produces several single-varietal vintages annually. Following vinification, Unconditional is aged in oak for eight months, ten percent of which is new wood, and ninety-five percent French (the remaining five percent being American).

A good Thanksgiving wine value: The man on the obverse of this bill might disapprove of your selection, but you could purchase several bottles of Unconditional with just one Benjamin.

Pinot noir is so often touted as the perfect Thanksgiving wine that recommending one for this meal seems almost obligatory. The venerable grape almost begs to be made into unassuming and versatile crowd-pleasing wines, light enough in body and not too potent to accompany several hours of feasting, and it’s capable of great complexity without relying on overpowering flavors that could clash with the traditional holiday fare. Battle Creek’s 2017 Unconditional Pinot Noir is no exception to this reputation, with a lovely nose of strawberry preserves and black cherry, a bit of earthy cedar, and a sweet, floral note of lavender. The palate is light, lively, and lush with jammy fruit, backed by a pleasant mingling of smooth tannins and a soft nip of acidity. There’s a touch of warming cinnamon in the dry, oaky finish – just the thing to complement the hearty spicing of an autumn meal – along with a final puckering punch of pomegranate.

Undoubtedly, Benjamin Franklin would find the craven and unscrupulous eagle undeserving of the defiantly bellicose pose it assumes on the label of Unconditional. And we also admit that the wine’s uncompromising name, with its implication of military surrender, makes an odd recommendation for a holiday that’s supposed to be about thanks and reconciliation. But we at Birds and Booze trust that – particularly after downing a glass or two or three – this Unconditional Pinot Noir will provide you with the fortitude and boldness to battle your way through the Thanksgiving meal – whether you find yourself coping with an uncomfortable quantity of food, politically disagreeable family members, or perhaps a controversial argument about the moral character of two equally iconic American birds.

Good birding, happy drinking, and happy Thanksgiving!

Good birding, happy drinking, and happy Thanksgiving!

Battle Creek Cellars: Unconditional Pinot Noir (2017)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Leave a Comment