In the heat of summer, it’s dragonfly time. The Dragonfly Society of America (DSA) is meeting in Boise, Idaho as I type. Here in New York City, Common Green Darners are zooming over park meadows, Seaside Dragonlets are starting to emerge in Long Island’s salt marshes, and naturalists exploring parks just a little bit north are finding Halloween Pennants and Black-shouldered Spinylegs. It’s time to place Dragonflies of North America on the top of my reference pile. This hefty volume, part of Princeton University Press’s Field Guide series, is one of my favorite identification guides of all time; it offers quick expertise, exquisite artwork, and its publication is a triumph of author and illustrator Ed Lam’s perseverance and devotion to the insect order Odonata, specifically the suborder Anisoptera–Dragonflies!

Dragonflies of North America covers identification of 329 dragonfly species, from the widespread Cherry-faced and White-faced Meadowhawks to local species like Texas Emerald to rare species like White-tailed Sylph. It’s important to note that the guide covers only dragonflies, not damselflies, which belong to the suborder Zygoptera. Lam covered damselfly species of eastern Canada and northeastern United States in Damselflies of the Northeast (Biodiversity Books, 2004), in many ways the forerunner of this guide. Damselflies tend to be smaller and fly lower with wings the same size; their eyes are separated by the width of an eye, and they usually perch with their wings closed (but not always, watch out for spreadwings!). Lam reviews this and other basic and not-so-basic information in ten short front-of-the book chapters covering life cycle, anatomy, finding and identifying dragonflies, the seven families, identification basics, catching and collecting dragonflies. Back-of-the-book sections include “In-Hand Characters,” Acknowledgments, a very short list of Resources, and a Species Index, divided into Common Names and Scientific Names. Surprisingly, there is no glossary, though anatomical and other scientific terms are explained in text. The guide’s North American geographic coverage is the United States and Canada, which is acknowledged in the introduction.

The introductory material is fully illustrated with Lam’s excellent technical drawings, showing items such as emergence from larva to teneral (newly emerged adult), wing parts, abdomen segments (very important), sexual anatomical features (also very important), common perch positions, comparison of the silhouettes of the different families, overhead flight silhouettes of selected constant fliers, and examples of how color and pattern of a species may change over their lifetime. The drawings give a textbook quality to the chapters and make it easier to learn anatomical features than most other dragonfly guides I’ve used. I did think that I learned more about other facets of dragonfly life, particularly behavioral characteristics like feeding, from Dennis Paulson’s two dragonfly guides: Dragonflies and Damselflies of the West (PUP, 2009) and Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East (PUP, 2011). Lam’s chapters on observing, catching, and collecting dragonflies are worth reading to get an up-to-date view of current field practices, which have been changing with the advent of good close-view binoculars and digital cameras. For those who want to try netting specimens, where the practice is permitted, Lam gives instructions, cautioning that it’s not as easy as it seems; also, do not harm the dragonfly! (Take it from me, this takes a lot of practice and in-person instruction helps a lot.)

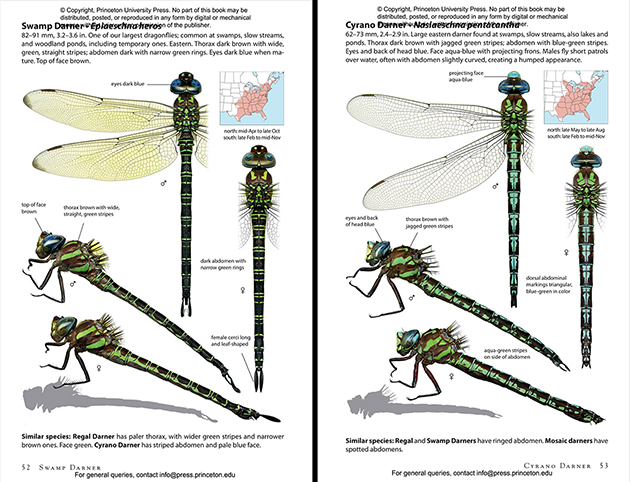

©2024 Ed Lam; page 52, Swamp Darner & page 53, Cyrano Darner

Species Accounts are organized by family, following taxonomic order, beginning with Petaltails, ending with Skimmers. The extensive introductions to each family section are important and helpful readings; they summarize shared physical, behavioral characteristics, and habitats for the family as a whole and for each genus within the family. In most family intros, Lam details the number of species worldwide and the number in North America, sometimes for the family as a whole, sometimes for each genus. These sections are illustrated with gray-shaded close-ups of head, abdomen, leg, and wing details.

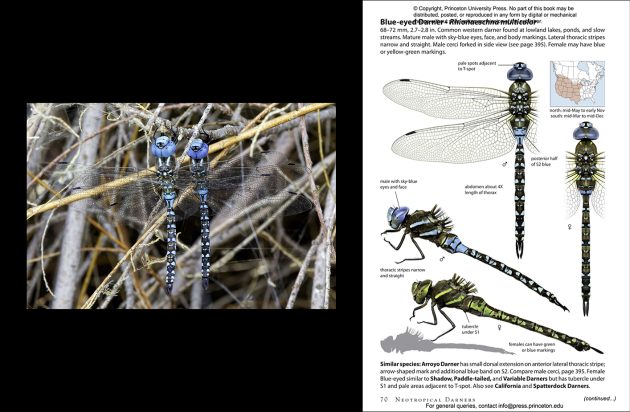

Most species are allocated one full page, even species that have few records in North America, though a couple of south Texas species do share a page. Lam’s meticulous depictions of the dragonfly’s body in vertical and side poses appropriately dominating the page. The poses are uniform: dorsal view (from above) of male and female, including a dorsal view of the male with his wings (female wings included if significantly patterned); lateral view (from the side) of male and female. I couldn’t find an explanation of the gray silhouette at the bottom of the drawings, they appear to be an outline of the dragonfly as it typically perches (some silhouettes have curved abdomens, some are straight), comparatively sized. If so, this is a useful visual since the drawings are all the same size. Enlargements and other details are included when necessary, such as the additional depictions of the variable wings of Banded Pennant. Several species are allocated two pages to show subspecies and variations, often an Eastern and Western form; these include Russet-tipped Clubtail, Swift River Cruiser, and many of the Meadowhawks.

The drawings really are the main text, their use expanded with readable captions pointing to significant identification features. The brief print text at the top of the page gives common name (based on names listed by the DSA), scientific name, size, and a summary of physical appearance, habitat, and identification features to look for (also depicted and pointed out in the artwork). There is little about flight patterns and speed, this is covered in the family and genus introductions. Similar species are listed and briefly described at the bottom of the page. The importance of his section can’t be understated, just take a look at the two species, Swamp Darner and Cyrano Darner, in the above illustration. There is also a small species range map, below which is printed the distribution range, the months in which you are likely to find the species. Lam warns in the introduction that the range maps should be used carefully: most dragonfly species are highly habitat-specific and are not likely to be found everywhere in the indicated range. Also, the dragonfly (and damselfly) knowledge base is still growing, which naturalists contributing documentation of species new to an area every year to citizen-based databased like iNaturalist and Odonata Central.

Blue-eyed Darners–Photograph (by review author) and field guide depiction ©2025 Donna L. Schulman, photography of Blue-eyed Darners, Piute Ponds, CA & ©2024 Ed Lam, page 70, Blue-eyed Darner

Ed Lam is a graduate of Cooper Union and received a Master of Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts and has a long, productive career in editorial illustration, natural science illustration, and most recently, art instructor and partner at the Schoolhouse Studio, a Westchester, N.Y. art school founded by his talented wife, Anne O’Connor. Followers of Lam on social media also know him as the active, baseball coaching dad of three boys, for whom he’s designed incredible Halloween costumes. Dragonfly enthusiasts know Lam as an active participant in the activities of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas, designing t-shirts, attending conferences, aiding with identifications, and as the author of Damselflies of the Northeast (2004).

Lam writes a little bit about the origin of Dragonflies of North America in his Acknowledgments: inspired by the damselfly guide, Lam’s soon-to-be literary agent suggested he write a more comprehensive book and in 2006, Lam signed a contract with Houghton Mifflin to write the “Peterson Field Guide to North American Dragonflies.” Lam’s personal website details the first few years of nonstop research, involving trips across and around the continent to collect and scan specimens. These accounts are worth reading to get an idea of just how challenging it can be to find specific dragonfly species, even with the help of dragonfly friends and local naturalists: hot days, windy days, cold days, dragonflies just out of net’s reach, dragonflies with deformed wings, male dragonflies but no female dragonflies, GPS directions that lead to nowhere, falls into deep streams, mosquitos–lots of mosquitos, and as the years advance, the challenge of juggling a growing family and the project. Lam’s tales end in the summer of 2009 and I can’t tell you what happened over the next decade, but in 2021, the Books & Media segment of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt was acquired by News Corp. and became part of the subsidiary, HarperCollins. But not all their books–a handful of unpublished titles were sold to Princeton University Press. And that included the dragonfly guide. Thank goodness.

Dragonflies of North America by Ed Lam is a significant achievement in the world of insect field guides. It combines comprehensive coverage of North America (U.S. and Canada) with highly detailed, educational, stunning color illustrations of each species, showing male and female bodies and wings and variations. It also offers introductory and important, supplementary identification material. The latter, the section on “In-Hand Characters”, shows over 300 close-ups of the anatomical structures, mostly sexual features, that need to be identified in-hand for identification of certain tricky species, each ‘structure’ drawn and shaded in black-and-white-and-gray pain-staking detail. Dragonfly enthusiasts are fortunate, this is a field full of identification and field guides, from the previously cited North America guides by Odonate guru Dennis Paulson to local guides by experts like Kathy Biggs (California, Southwest), John C. Abbott (Texas and South-central U.S.), Giff Beaton (Georgia and the Southeast), and Blair Nikula (Massachusetts), to name some of my favorites. Most dragonfly guides use photographs,* lots of photographs. This is why Ed Lam’s artwork makes his guide so unique. Photos are great and these guides have lovely images, but it is much easier to learn distinguishing, tiny, structural features from drawings than from photographic images which have backgrounds, shadows, and sometimes color issues. Also, if you are a fan of the art of scientific illustration, then I think you will find it hard to resist examining a field guide in which every technical illustration is also simply beautiful. Dragonflies are beautiful, so maybe this isn’t such a stretch, but so many dragonfly paintings indulge in whimsical swishes and pastel color washes. Ed Lam shows us the beauty in intricate wing cells, striped thoraxes, and segmented abdomen that may turn chalky white with age; in huge eyes that may be white or green or gray set in faces than are red or white or green-gray. His drawings enchant and make us impatient to go outdoors and observe the soaring, hawking, patrolling, mysterious predators we call dragonflies.

* An exception is Abbott’s Damselflies of Texas: A Field Guide, which features Lam-type drawings by Barrett Anthony Klein in addition to photographs. It’s possible that the lower number of damselfly species makes it easier to write field guides for this suborder with original art.

————————————

Dragonflies of North America

Written and illustrated by Ed Lam

Princeton University Press, Oct. 2024

448 pp.; 5.5 x 8.5 in.; 1,850+ color illustrations

ISBN-10 : 0691232873; ISBN-13 : 978-0691232874

$35.00, hard cover; eBook version also available from publisher (price lower from the usual suspects)

Donna, this is really a thorough and excellent review of Ed Lam’s fantastic book. I pre-ordered the book last fall and when it arrived on my doorstep, I think I was one of the first to be a proud owner. I don’t net dragonflies – partially for the reasons you warn about – but also because I’m on my own with camera and bins and have trouble managing the net with those accoutrements. I’ve come to learn the hard way that some Odonata can only be identified in hand. So learning to net and properly handhold a dragonfly or damselfly is important. I recently found and photographed a dragonfly, that was perched overhead, so photographing was difficult. I thought I was seeing something new for me. I thought I was looking at a yellow dragonfly with red streaks or stripes on its thorax, gray eyes, black legs, gray stigma. I couldn’t believe it when I could not find what I had seen and photographed in Lam’s book. I finally gave up and emailed my photos to an expect resource who had helped me in the past. ID: female Blue Dasher. So common, so embarrassing. This was the ID that I thought closest to what I had observed in the field. But, I had never seen a yellow thorax with reddish streaks, gray eyed female blue dasher. I have the book open to Blue Dasher as I write this and, even knowing that this is what I saw, I still cannot get it to quite match up. How many times have I seen and photographed female Blue Dashers? Countless. I find them more attractive than the male. Just goes to show that experience in the field is so important and, at the same time, never enough. Dragonflies or damselflies are not like birds. They are so challenging. As I’m writing this I realize that I overlooked a small, but significant detail that Lam goes to the trouble of pointing out and this detail is visible in one of my photos. This comment is already way too long, but I was dismayed to find out that his Damselfly book is out-of-print and, if you can find it, is very expensive. Perhaps Princeton Field Guides could reprint? Looking forward to your end-of-year panel book review with Nate Swick and others on the ABA podcast – my favorite episode each year.

Thank you so much for this long, expansive comment, Cathy. I understand your confusion about that female Blue Dasher–dragonflies & damselflies can look very different depending on the angle. And thank you so much for your appreciation of the ABA best-of podcasts–I look forward to doing it too, though making the selections can be difficult.

Good news on the Damselfly guide front–Ed Lam wrote on his FB site that he is considering doing an expanded version (not the whole U.S., probably expanding the Northeast coverage).

This is good news about Ed Lam’s Damselfly guide. The NE part would work pretty well for me. When I was looking into the status of the book’s availability I remember reading a review by a guy, who I think identified mostly as a birder, and said he had seen a lot of field guides in his day; he called Ed Lam’s Damselfly book was the best field guide he had ever seen.