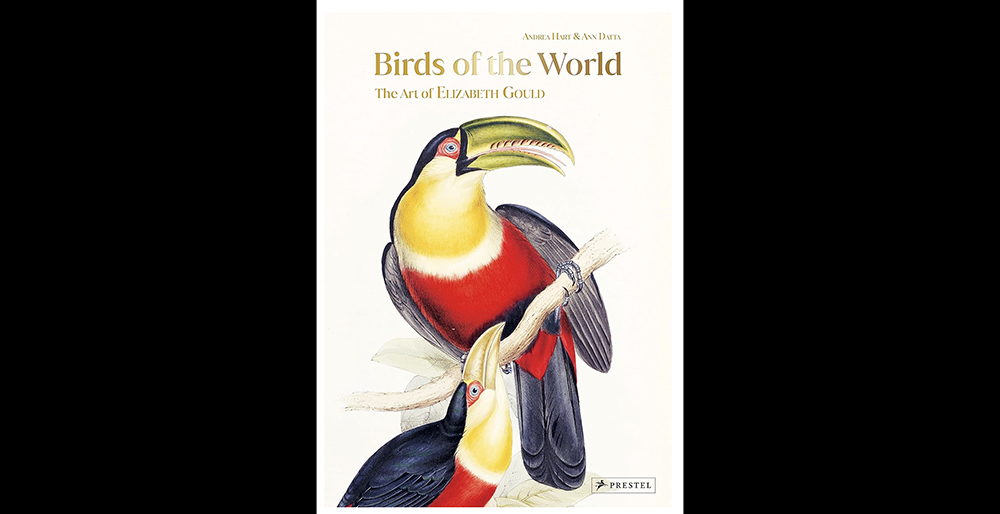

I don’t remember where I first learned about Elizabeth Gould–possibly when I was birding Doi Angkhang, Thailand and saw a stunning little bird named Mrs. Gould’s Sunbird–but I have been fascinated by her story and her art for the past five years. When I saw that a book had been published about her, I ordered it even though it’s an oversized art book (some would say coffee table book), a type of book I seldom buy or read. And I’m so happy I did. Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould, written and edited by Andrea Hart and Ann Datta, is a superb, thoughtful collection of the work of an artist who made substantial contributions to the practice of scientific illustration and to our knowledge of birds in six continents, yet who for many years was overshadowed by her famous spouse, ornithologist, collector and taxidermist John Gould.

This is the only known portrait of Elizabeth Gould. The image here is from the Wikipedia entry on Elizabeth Gould; it is designated as in the public domain and it is noted that it is “from an oil portrait by an unknown artist, painted after Elizabeth’s death in 1841.”

Elizabeth Coxen was born in England on 18 July 1804 (a significant date since I also was born on July 18th!) and died 15 August 1841. In her 37 years she married John Gould at age 24; birthed eight children, six of which survived infancy; ran a household that housed both family and book production facilities in Soho, London; and worked with her husband to produce eight ornithological works on birds of the Himalayas, Europe, South and Central America (with some North American birds mixed in), and Australia. She also produced 50 bird plates, including the famous Galapagos finches, for Darwin’s The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. In 12 years, Elizabeth Gould designed, drew, and colored more than 650 lithographic plates of birds, plus drawings of Australian birds and plants that contributed to the volumes of Birds of Australia published after her death. Twelve years! That’s a work life of 144 months, half of which she worked while pregnant (reminding me of the adage that Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did only backwards and in high heels). Yet, for decades Elizabeth Gould was the ghost of 19th-century ornithology, her work unaccredited or largely attributed to John Gould.

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould is divided into three parts: (1) “Elizabeth Gould (1804-1841), The life of the gifted artist,” an 18-page summary of Elizabeth’s life and art, including a helpful description of the process of lithography, a bibliography, and a very brief “Introduction to the Plates”; (2) “Plates,” divided by continent in the order in which the Gould publications were created (Asia, Africa, Americas, Australia) with a section on “Drawings” wedged between Europe and the Americas; (3) back-of-the-book sections: Acknowledgements, Appendix, Index.

You don’t have to go to the Plates section, though, to start appreciating Elizabeth Gould’s art. The cover shows two Red-breasted Toucans, one adult, one juvenile, their bright colors and curved lines filling the rectangular borders. Once you open the cover and flip over the blank red first page, you are unexpectedly met with a close-up of the pink face and rose-pink and white and golden plumes of a Pink Cockatoo, one of the most stunning birds in the world (formerly known as Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo, the name used here). Next is a delicious double-page spread of Spotted Bowerbirds, male and female, at their bower, the lilac-pink crest of the outside bird shimmering amidst carefully delineated lines of brown and buff-spotted plumage, shell and bone adornments in the foreground, Australian landscape in the back. A two-page portrait of Cuban Trogon is next, its blue, green, red, and white plumage shining, then a two-page depiction of three Ruffs in male summer, male winter, and female plumage, and finally the Galapagos Short-eared Owl on the alert, facing the title page.

![]()

This is NOT an image from the book. It is an image of the Spotted Bower Bird plate by Elizabeth Gould from Birds of Australia, made available to the public by Rawpixel, who notes the image has been “Digitally enhanced from our own facsimile book (1972 Edition, 8 volumes)”, https://www.rawpixel.com/image/321196/free-illustration-image-gould-illustrations-bowerbird The Spotted Bower Bird image presented in Birds of the World has cropped the image so there is no label and no white border.

These images are a wonderful cross-section of Gould’s best work, pulling from books on Toucans, birds of Australia, Trogons, Europe, and Darwin’s Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. They are seen again in the body of the book, smaller and captioned, part of a progression of images that helps one appreciate Gould’s development as a scientific illustrator and artist. Elizabeth’s first book assignment was given to her by John Gould about a year into their marriage. A self-taught, ambitious man, John had obtained the position of curator and taxidermist at the museum of the Zoological Society of London. The story goes that having received a large number of bird skins from the Himalayas, many of them not described scientifically or known to the English naturalist community, he decided to publish a large, illustrated book about them. And, the story further goes, when Elizabeth asked who was going to paint the birds, he replied “Why you, of course!” A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, sold by subscription, was published between 1830-33. It was a great start for Elizabeth, though she first had to learn the new artistic practice of lithography. Her teacher is assumed to have been a very young Edgar Lear, who learned the art because he wanted to produce his own book on parrots and who also did illustrations for John Gould.

All of Elizabeth’s birds were drawn from skins, though the Birds of Europe images benefitted from her observations of real live birds. Unlike Audubon, she didn’t pose the skins. Most sources, including this book, say that John would draw a rough sketch of the composition he wanted, and Elizabeth would draw and create the lithographic plates. Lithography was a new and relatively inexpensive way of creating many illustrations, but it wasn’t easy. In the introduction, Hart and Datta delineate the many steps involved, starting with drawing on a large stone with greasy crayon and ending with colorists hand-coloring based on Elizabeth’s template (with John Gould checking the proof between printing and coloring). They note that lithography was “painstaking, back-breaking work, as it involved leaning over a large stone for long periods….It is hard to imagine a more soul-destroying task for an artist, and especially for Elizabeth, who continued to work on the stones during her pregnancies” (p. 19). There is evidence that as Elizabeth became more proficient, she would do the drawings herself, with only some corrections from John.* As the one example given in the book shows, John painted with broad, rough strokes. Elizabeth drew with fine, soft lines, using colors and brushwork to create diverse plumages and backgrounds.

Birds of the World shows 39 lithographic illustrations from the Himalaya book. The images are striking, particularly those of male and female Western Tragopans, one in brilliant red and blues, the other cryptically, intricately patterned in browns. They are also a little stiff and sometimes a bit out of proportion, the Rosefinches, Redstarts, and Minivets perched on branches sketchily drawn with no background. A pioneer in bird illustration, though she most probably didn’t know it at the time, as we go through the book, through Europe and the Americas, we see Elizabeth growing increasingly sophisticated in composition and design, incorporating plants and trees of the birds’ habitats, showing birds in poses that indicate movement and behavior, placing them next to nests and feeding their young.

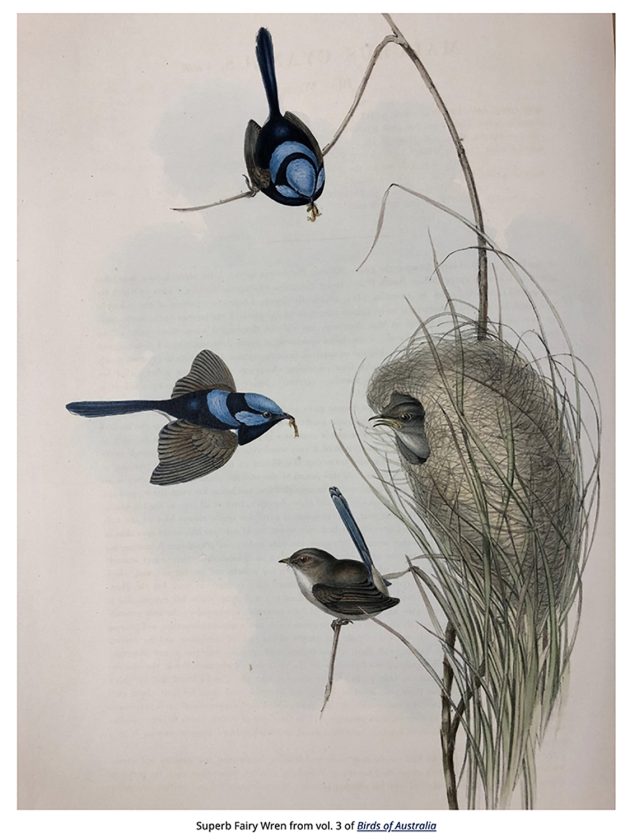

Plate reproduced on Amazon page for Birds of the World in a section titled “From the Publisher”

The lithographs and drawings of the birds of Australia are the culmination of Elizabeth’s art. Elizabeth spent two years in Australia, traveling there with John and her oldest son, then living with acquaintances and relatives in Tasmania, Sydney, and Yarrundi while John traipsed across the continent shooting birds, collecting skins. When she wasn’t giving birth to her seventh child, Elizabeth studied and sketched birds (caged and wild) and plants, and when she returned to London (and to her other three children), she started drawing and creating lithographs. In this plate, she shows Superb Fairy-Wrens (then known as Blue Wrens) feeding a youngster in the nest, unfortunately a Cuckoo (probably a Horsfield’s Bronze Cuckoo). This may be before the Fairy-Wrens developed the ability to detect Cuckoo young in the nest, an ability recently described by ornithologists, or this family may be one of the 60% who don’t detect Cuckoo chicks. Either way, Elizabeth’s image is probably one of the earliest portrayals of this behavior.

Tragically, Elizabeth died of puerperal fever in August 1841, five days after giving birth to her eighth child. Puerperal fever was common then, it is what happens when your birth doctor or midwife does not wash his or her hands. She had prepared 80 plates for the Australia book before she died and 84 of the plates in the final volumes are attributed to her (assumedly this includes some of the plates based on her drawings). John mourned her and named the beautiful Gouldian Finch after her but does not appear to have lost much time finding successors for the multi-volume book on birds of Australia and numerous later books. He never remarried; he died in 1881 at the age of 77.

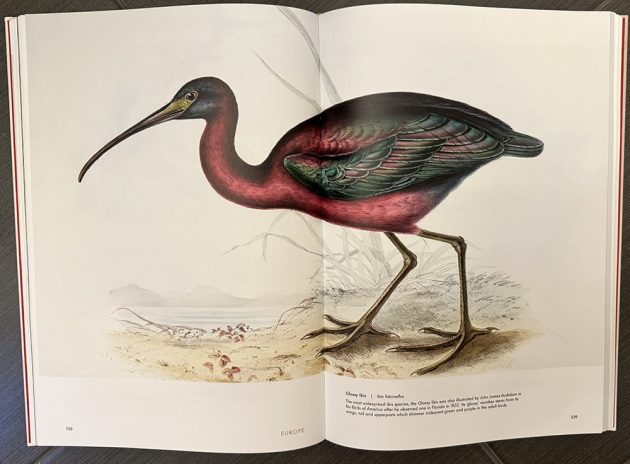

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould reproduces 180 lithographs and 32 drawings selected from the eight bird publications Elizabeth worked on with John, the Voyage of the Beagle, several individual early works drawn for colleagues of John, and an album of drawings by “J and E Gould.” Although the introduction does not specify how these images were chosen from Elizabeth’s large body of work, in an interview with Oli Haines, available on the NHBS website, the authors admit that the selections do include most of their favorites: “Ann specifically likes the bowerbirds, the Narina Trogon, the quetzal and the Australian wren and Andrea became quite fond of the toucans (but also had to include a magpie).” Similarly, the authors do not go into details about the process of reproducing the lithographs and drawings (this was mostly probably done by the publishing team), but you can see in the images below that it involved work. The first image is Glossy Ibis as reproduced by the Biodiversity Heritage Library from the Smithsonian’s Birds of Europe, volume 4.

The second image is my rather poor photograph of Glossy Ibis from Birds of the World, as reproduced from the volume held by the Natural History Museum of London. Not only is the book reproduction cleaner and the colors brighter, it is slightly cropped so that the bird jumps off the page at you, but also cropping out the species name. Instead, a brief paragraph gives the common and scientific name, as it appeared in the book, and a bit of background information about this species, also painted by John James Audubon. As I sit here with the book in my lap, I’m searching my brain for words to describe how the Ibis illustration looks in person. Elizabeth Gould’s fine lines and subtle use of color magically brings to life the way Glossy Ibis plumage shimmers and shines in the sun. So much better than the photograph.

Captions for the plates and drawings are variable. Some, as with Glossy Ibis, are about the bird itself–its current vulnerability status (quite a few of the birds pictured here are now critically vulnerable, endangered, or even extinct), its variable plumage, or notes on its mating behavior. To me, the more interesting captions are about the illustration’s history–the process of drawing the bird, problems in obtaining or identifying a specimen. Elizabeth’s experience and ingenuity, for example, can be seen in her lithograph of Langsdorff’s Aracari; there was only a single specimen in a German collection and its tail was mutilated, so she obscured the tail in her plate by placing it behind a large leaf (pp. 168-168). Issues of authorship are also explored. Elizabeth’s watercolor of the Australian Mulga Parrot, for example, was used as the basis for H.C. Richter’s lithographic plate in The Birds of Australia (Richter succeeded Elizabeth as illustrator for the Australia volumes after she died); the authors point out that the lithographic plate is an exact copy of the drawing (p. 148). The number of drawings that were used for The Birds of Australia after Elizabeth’s death, birds and plants, emphasizes her influence on John Gould’s body of work and the excellence of her eye and hand.

As I said before, the book plates utilize the species names used in the original books and drawings. Early Gould works and some of the later Australia images did not have common bird names (they did not exist at the time for the Himalayan and African birds), so the plates in Birds of the World caption these images with the line “No Gould common name” followed by the scientific name of the time. The reader-friendly thing to do, of course, is to include the common name in the text underneath or next to the image, and in some cases the authors do this, but they don’t for many other plates, which means you have to check the appendix in the back. It’s a cumbersome system, and rather puzzling to find in a book authored by librarians.

The Appendix is a lengthy listing of every image by page, including those in the front and back of the book and in the introduction. Each entry lists the current common and scientific names of the bird and its source, including plate number and year. I found myself going back and forth between plates and the Appendix, searching for common names and book titles, wishing the book had a ribbon attached that would help me keep my place in the appendix.

Rather than using a specific taxonomy, the authors relied on Hein Van Grouw, Senior Bird Curator at the Natural History Museum, Tring, for current common and scientific names (many of the names used by Gould have been changed, especially the scientific ones). As mentioned above, the book retains the name Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo for Pink Cockatoo (which was called Leadbeater’s Cockatoo in Gould’s time). Thomas Mitchell had a brutal history of killing Aboriginal people, and in 2023 Birdlife International and the Royal Australasian Ornithologist’s Union officially renamed the bird. I like to think that the change occurred after the book went to press, though I know the MM name is still commonly used.

There are two indexes that list current common names, current species names, and page numbers in three alphabetical columns. In other words, you can look up birds by the full current common name or by their full species name. It’s a clunky system that only works IF you know the full name of the bird you are researching. So, you can’t look up “Toucan,” but you can look up “Channel-billed Toucan” or “Orange-breasted Toucan.”

In the introductory section (time to go back to the beginning!), the authors tell the story of Elizabeth’s life, from girlhood through her short stint as a governess through early married life, childbirth and children, and, most extensively, her beginnings and development as an artist. Brief but specific social and historical contexts are provided, including a map of the section of Soho, London where Elizabeth and John lived, a photograph of their 5-story townhouse, and, as mentioned above, a step-by-step description of the lithographic process. The Bibliography is a useful listing of original Gould publications (by both Elizabeth and John) and secondary publications, though they don’t include material by Melissa Ashley, an Australian writer and researcher, Alexandra K. Alvis, an American book historian who’s written and done a webinar on Elizabeth Gould, or Corryn Wetzel’s excellent article on Elizabeth in Audubon Magazine.

How did Elizabeth become a ghost? Although she was credited on the plates of the first Himalayas book, the plates of the next seven books gave dual credit with the line “drawn from Life & on Stone by J & E Gould.” There is no signature or accreditation on the Galapagos plates, though Darwin credits “Mrs. Gould” with executing John’s sketches on stone “with that admirable success, which has attended all her works.” The title page of every one of the lavish, illustrated books co-created by John and Elizabeth say “John Gould.” There is Elizabeth’s short life, John’s long life, John’s domineering personality, the societal norm of considering a wife the helpmate of the husband, and the historic fact that scientific illustration itself was not yet a recognized field. Put it all together, add a lack of primary sources about Elizabeth’s feelings about her work and her artistic process, and it becomes a little more obvious how Elizabeth’s achievements were until recently unrecognized. There is a small body of research which has sought to weed out Elizabeth’s artistry from John’s, including articles in feminist journals and a fictional biography by Australian writer Melissa Ashley. Interestingly, this literature is not cited or summarized by Hart and Datta. They do offer an alternative way to look at Elizabeth and John’s partnership, offering a complexity that goes beyond the simplistic idea that Elizabeth was a martyr to John’s ambition. Elizabeth was as driven in her art as John was in his ornithological projects, they say, and John’s assignment to illustrate his books was “an outlet for her latent artistic gift” (p. 27). If the partnership was less than a partnership of equals, it was because of a culture that did not value the work of women or nature artists. I like the first part, I have doubts about the second part, which ignores that fact that John Gould was a strong personality who also gave less than equal credit to his male illustrators. I wish I had a time machine so I could go back in time and tell Elizabeth to somehow, amidst all her duties, keep a diary.

Authors Andrea Hart and Ann Datta are not new to writing and editing books about the Natural History Museum’s collections. Hart authored Women Artists: Images of Nature in 2014, a book showcasing the works of women naturalists, scientists, and amateurs in the museum’s collection, including Elizabeth Gould. She’s also produced books on the Art of British Natural History (2017), Expeditions and Endeavours. Images of Nature (2018), and an essay on illustrator Sydney Parkinson in Nature’s Explorers Adventurers Who Recorded the Wonders of the Natural World (2019). Ann Datta has been the Museum’s zoology librarian since 1969. Her many articles and books include John Gould in Australia: Letters and Drawings (1997).

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould is the first publication to celebrate Elizabeth’s art and life. Published by Prestel Publishing, a German art publisher that’s part of Penguin Random House, with offices in London and New York, it’s a beautifully packaged art book, large (9.63 x 1.13 x 13.81 in.) but not too large, and not overwhelmingly heavy. It is co-branded with the Natural History Museum of London, whose collections are the source of the artwork. There is some irony in the UK finally paying its respects to Elizabeth Gould, who has previously been honored more in Australia and the United States than in her home country, with educational webpages hosted by the Australian Museum Archives and Research Library and the University of Kansas, an exhibit at the University of Tennessee, and a 2019 webinar hosted by the Smithsonian Libraries. A little late, but very well done. This is a significant book, especially if you are interested in bird illustration and women’s role in ornithology. And it’s so well designed! Every effort has been made by the design and layout team (Andreas Kalamala and Liane Gotzelmann) to show off Elizabeth’s Gould art, from the front and back covers to the opening pages to the pages separating each section. Come for the life of Elizabeth Gould, stay for the joy of perusing her birds.

* Alvis, Alexandra K., “Elizabeth Gould: An Accomplished Woman,” appearing in Smithsonian Unbound, the blog of the Smithsonian Library, March 29, 2018. https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2018/03/29/elizabeth-gould-an-accomplished-woman/

————–

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould

by Andrea Hart and Ann Datta

Prestel, Nov. 2023m

Hardcover, 248 pp.; 4.21 pounds; 9.63 x 1.13 x 13.81 inches

ISBN-10: 3791379879; ISBN-13: 978-3791379876

$70, discounts from the usual sources

Leave a Comment